The Sogdians at Home

Art and Material Culture

by Julie Bellemare and Judith A. Lerner

Over the last sixty years, new finds of Sogdian visual and material culture have allowed scholars to build up an increasingly detailed picture of the Sogdians’ extraordinarily rich, varied, and expressive artistic traditions, from large-scale mural painting to finely wrought metalwork.

What’s special about Sogdian art? Despite the great variety of media and subject matter, there are striking and recurring elements that appear throughout the wall paintings, clay and wood sculpture, and metalwork that make up the major surviving examples of Sogdian visual culture. First, Sogdian artists, artisans, and their patrons demonstrated a keen attention to social life, such as banqueting, hunting, and entertainment. Second, they had a true passion for telling stories, from folk tales to literary epics, to the point of illustrating their domestic interiors with narrative paintings. Third, because of their commercial activities they encountered neighboring societies, and their art strongly reflects their awareness and acceptance of cultures unlike their own. Fourth, this interconnectedness with other Eurasian cultures is especially apparent in Sogdian religious art, which is extremely diverse and reveals their unique vision of the divine and the afterlife. In this essay, we explore a selection of key works that pertain to these themes.

The Good Life

The Sogdians certainly knew how to enjoy life’s pleasures, such as food, wine, and entertainment. They banqueted with silver and golden tableware, such as this gilded silver cup with mountain goats and vegetal decoration; Figs. 1–3.

Its ring handle with thumb rest and its bulbous body with narrowed neck is generally associated with Turkic steppe peoples—neighbors and allies of the Sogdians; Fig. 4. Stylistic analysis suggests its manufacture by a Sogdian craftsman who belonged to a particular school of metalwork, characterized by the ropelike border of the roundels that enclose each goat, the alternating leafy and half-palmettes, and the flat, ring-matted pattern on the neck. The motif, which may have been chosen to please a Turkic patron, is a pair of grappling wrestlers depicted on the thumb rest, and it is possible that someone watched a wrestling match while drinking from this cup.

BanquetingBanqueting in Sogdiana Learn more about banqueting in Sogdiana would also have been the use for this gilded silver wine cup with elephant heads on the thumb rest, Figs. 5-7, and for the deep, many-lobed bowl decorated with a medallion of a lion seated in front of a bush; Figs. 8–11. The winged camel ewer in Figs. 12–14, an outstanding example of Sogdian metalworkSogdian Metalworking Learn more about Sogdian metalwork, would have been used to serve wine at a wealthy person’s table. The palmette at the base of its handle—a feature borrowed from Roman metalwork—is unique to ewers made in Sogdiana.

Related to the winged camel is another fantastic creature that appears on metalwork, thought by some scholars to be the senmurv or simurgh, a large, mythical bird with a doglike head, canine or leonine foreparts, and an elaborately feathered tail; Fig. 15. Although this benevolent creature is mentioned in later epics and poetry, Sogdians undoubtedly would have been familiar with it.

A Passion for Storytelling

Many archers; many charioteers; many demons riding elephants, … many riding pigs, many riding foxes, many riding dogs, many riding on snakes and on lizards; many on foot; many who went flying like vultures; … many upside-down, the head downwards and the feet upwards—all these demons bellowed out a roar. For a great while they raised rain, snow, hail, and great thunder; they opened their jaws and released fire, flame, and smoke. They departed in search of the valiant Rustam.

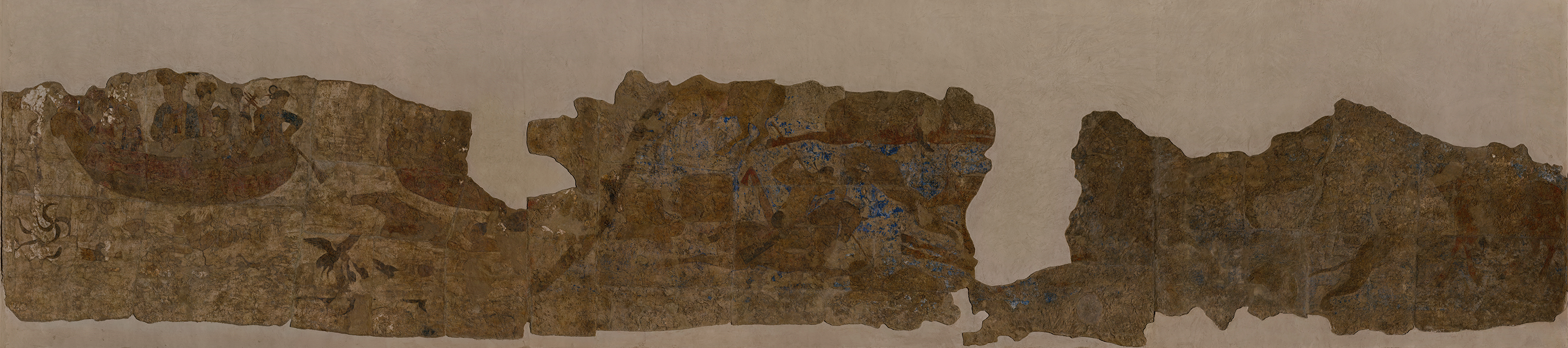

The battles and banquets in the epic of Rustam, quoted above, inspired the main cycle of paintings in the reception hall of an affluent Panjikenter’s house; Fig. 16.

Discovered in 1956–57, this hall, known as the “Rustam Room,” or the “Blue Hall” for its painted background color, stands out among other excavated examples for its exceptionally well-restored murals. These can be dated to around 740, just twenty years before the final destruction of Panjikent . This cycle of paintings epitomizes a striking feature of Sogdian figural art: its engaging narrative quality. Instead of the more static, mannered style that predominates in Sasanian Persia, Sogdian art focuses on the individually heroic in its preference for epic and historic narratives, yet it also includes popular stories; Fig. 17.

Fig. 17 Frantz Grenet (Collège de France) discusses Sogdian painting

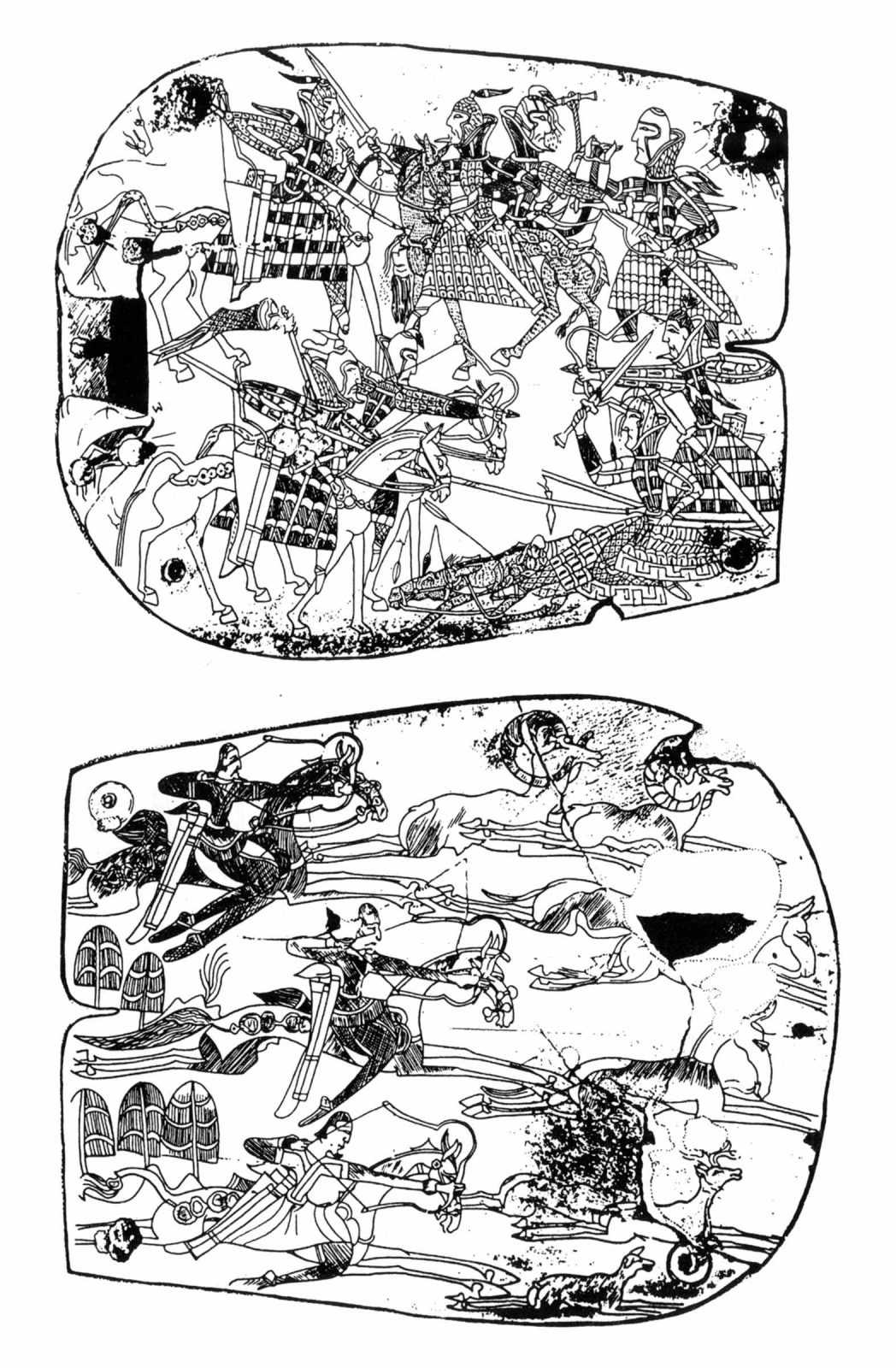

Figs. 18–20 Belt Plaque Showing a Battle Scene. Orlat cemetery, Kurgan No. 2, Uzbekistan, 1st–4th century CE. Bone; H. 11 × W. 13.5 cm. Institute of Art Studies, Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Uzbekistan, Tashkent, IX-278. View object page

Photograph © Institute of Art Studies, Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Uzbekistan.

This desire for narrative also prevails in the carved and painted funerary furniture—stone beds and sarcophagi—of Sogdians who lived and died in China. To convey narrative, Sogdian artists would include only the essentials. Lines, blocks of color, and a few landscape elements to set the scene create an easy-to-read two-dimensionality that helps advance the progress of the depicted tale. We may see the origins of this pictorial style on the pair of bone plaques in Figs. 18–20, depicting a battle scene found in Orlat , Uzbekistan.

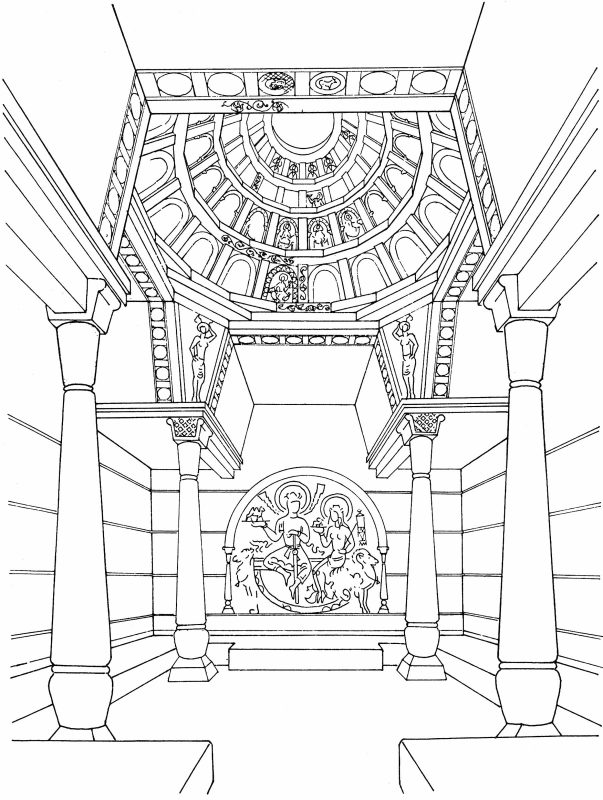

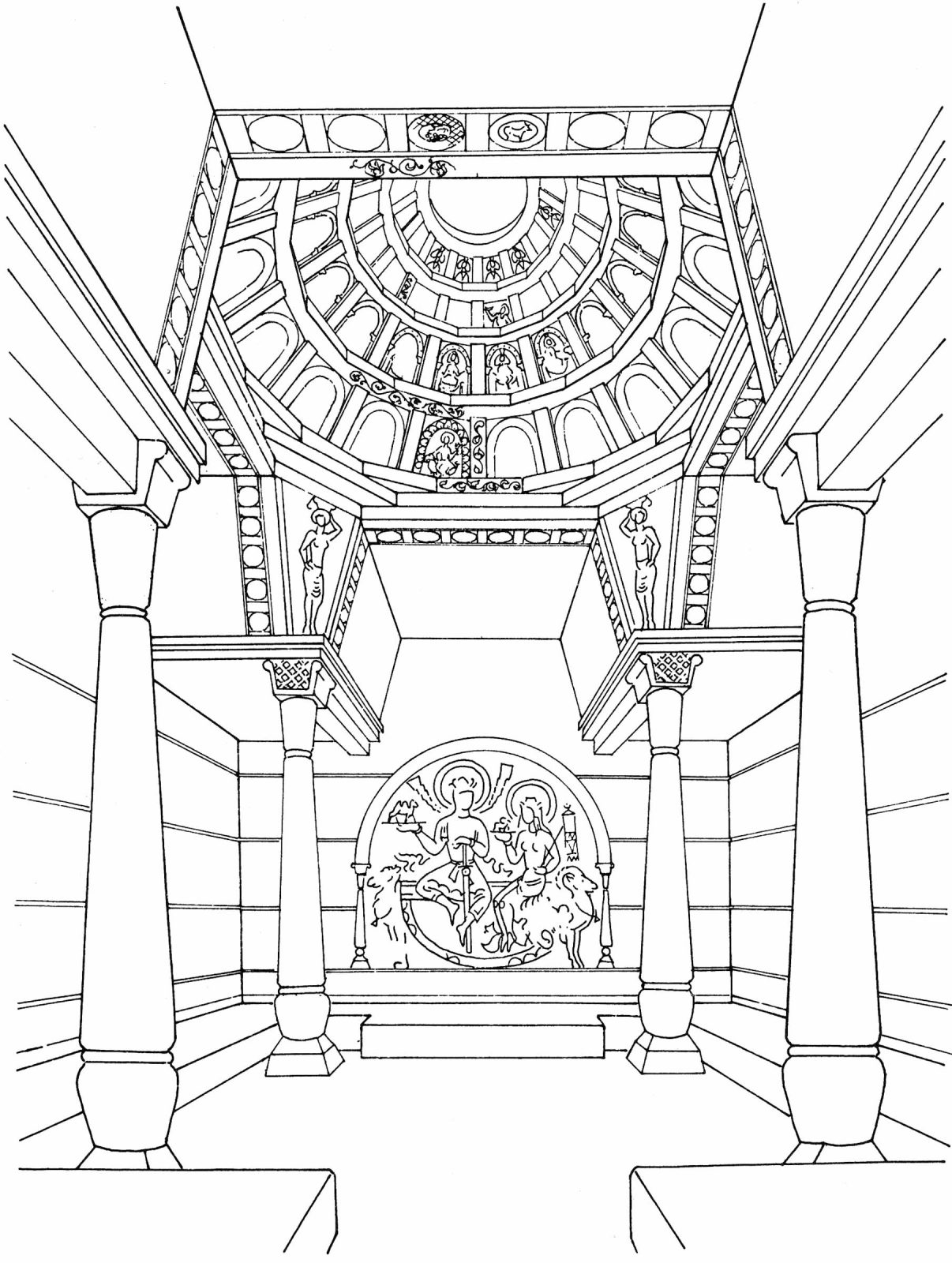

The walls of the reception rooms of well-to-do PanjikentersThe City of Panjikent and Sogdian Town-Planning Learn more about Panjikent and Sogdian town-planning were generally covered with up to four zones or registers of murals. The lowest would be directly above a low, plaster-covered clay bench (or sufa) that ran around the entire room. This is where the owner of the house and his guests could sit, talk, and dine. The wall opposite the entrance would be entirely taken up with a larger-than-life-size image of the divinity (or divine couple) held sacred by the house owner. The mural paintings organized in registers on the other walls typically depicted episodes from literature, ranging from great epics to folk tales and fables. Above these zones of paintings, the room would have been covered by a domed ceiling, Fig. 21, its surfaces embellished by carved wooden panels, Figs. 22 and 23, and caryatid figures, Fig. 24.

Fig. 22 (Left) Battle between Hero and Winged Lion; (right) Deity with a Peacock. Panjikent, Tajikistan (in ancient Sogdiana), Site XXIII:57, late 7th century CE. Charred wood; (left) H. 57 × W. 35 cm; (right) H. 56 × W. 40 cm. The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia, SA-16231-16230.

Photograph © The State Hermitage Museum.

Fig. 24 Caryatid Figure. Panjikent, Tajikistan (ancient Sogdiana), Site III:47, 1st half of 8th century CE. Charred wood; H. 115 × W. 21.5 cm. The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia, SA-15911. View object page

Photograph © The State Hermitage Museum.

Of the few surviving Sogdian texts, a rare example of nonreligious literature is the story of Rustam battling the demons, quoted above. As one of the best-known heroes of the great Iranian national epic the Shahnameh [Book of Kings], Rustam appears in the painting from the Rustam Room clad in a tiger or leopard skin. Mounted on his ever-vigilant red horse Rakhsh, he defeats the enemies of the kingdom. This incident in Rustam’s tale, however, does not appear in the Shahnameh and may be a Sogdian version that had a life of its own as a popular version of the tale.

The focal point of the Rustam Room is a large-scale painting of the goddess Nana, while the other three walls display a selection of pictorial narratives, divided by subject matter into four horizontal bands. Only a small portion of the uppermost register survives: two men in full armor stand guard next to hybrid animals, most likely representing a religious scene. The middle two registers focus on Rustam’s heroic battle against the daevas or deevs, supernatural creatures who incited evil-doing and chaos. Positioned at or slightly above eye level, the composition is arranged rhythmically, with groups of advancing riders alternating with duels and battles. The story unfolds as a continuous sequence of episodes, with only the most significant or dramatic moments shown; Figs. 25–31. Use of this format to present the tale sequentially mirrors the ancient oral tradition of storytelling. Indeed, we can imagine the host and his guests feasting on the carpet-covered sufas, reciting such tales before these stunning visuals. The long, horizontal format of the registers also reflects the use of painted scrolls as part of this ancient storytelling tradition.

Fig. 26 Detail: Episode 1. Rustam, on his horse Rakhsh and accompanied by his men, sets out on a campaign against the demons. They ride into a wild and dangerous region, as suggested by the white figure perched atop a rocky outcropping, its arms raised in anger and despair at the sight of Rustam. This is the White Demon (Div-e Safid), one of Rustam’s adversaries in the Shahnameh.

Fig. 27 Detail: Episode 2. Rustam enters into his first battle against another horseman, whom Marshak identifies as Avlad, ruler of the borderlands through which Rustam is traveling. The hero is pictured throwing a lasso around his opponent’s neck, while behind him a benevolent female deity bestows her heavenly protection.

Fig. 28 Detail: Episode 3. Rustam is in great peril as he fights a dragon that has coiled itself around Rakhsh’s legs, pulling Rustam toward its gaping mouth. The painting does not show Rustam’s escape from this dire situation, but part of the Sogdian text offers a version of how he did: “Rustam turned back, attacked the demons like a fierce lion upon its prey or a hyena upon the flock, like a falcon upon a hare or a porcupine upon a snake, and began to destroy them.”

Fig. 29 Detail: Episode 4. Both Rustam and Rakhsh emerge unscathed. Together with Rustam’s men they trample the dragon, its tail rising in the air in a final, violent convulsion.

Fig. 30 Detail: Episode 5. Rustam and the ruler of the deevs meet in single combat. In the course of their fight, their saddle girths break and the two adversaries fall from their galloping horses. Their duel on foot should follow, but the artist has omitted Rustam’s success over his adversary.

Fig. 31 Detail: Episode 6. Rustam’s men in battle with the deevs. Their success is assured by the beribboned lion-bird that flies towards them. In contrast, their subhuman adversaries are followed by a vulture that signals their impending defeat.

Figs. 25–31 Click on the hotspots to view details of the Blue Hall mural and read about the various episodes in the story of Rustam. The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, SA-15901-15904. View object page

Photograph © The State Hermitage Museum.

The lowest register features fables, parables, and folktales. Painted just above the sufa, most if not all of these stories would have been familiar to the guests, and their visual depiction would have entertained them, while also teaching life lessons. Below the Rustam cycle, approximately thirty panels contained scenes from Hindu animal fables of the Panchatantra, Buddhist Jataka tales, and Aesop’s fables. These last had their roots not only in ancient Greece, but also in the West and farther east, in Asia. Thus in another Panjikent reception hall (21/1), dominated by the two-registered Amazon Cycle (painted around the same time as the Rustam Cycle), the lower register contains two Panchatantra stories, while on the southern wall is the well-known story of “The Goose that Laid the Golden Egg”; Figs. 32 and 33. By surrounding themselves with illustrations of epics and fables, the Sogdians expressed their enthusiasm for storytelling.

The Outside In

Other works of Sogdian art illustrate an awareness of—and keen interest in—the outside world and neighboring countries. This is evident in their portraying people from other cultures and adopting foreign materials along with elements of style and content.

At Afrasiab (Old Samarkand) , the capital of the towns in the Samarkand oasis, Russian excavations in the 1960–70s unearthed a room (no. 1) in a multi-roomed structure. Dubbed the “Hall of the Ambassadors,” it features processions and other painted scenes on walls that rise above a sufa bench that runs around all four sides of the room; Figs. 34–38.

Fig. 34 Click to enlarge and scroll through the West Wall of the Hall of the Ambassadors. Afrasiab (old Samarkand), Uzbekistan (in ancient Sogdiana), Site XXIII:1, mid-7th century CE. Wall painting; H. 3.4 × W. 11.52 m. Afrasiab Museum. View object page

Photograph by Thorsten Greve © Association pour la sauvegarde de la peinture d’Afrasiab, and Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

Fig. 35 Click to enlarge and scroll through the South wall of the “Hall of the Ambassadors.” Afrasiab (present-day Samarkand), Uzbekistan (in ancient Sogdiana), Site XXIII:1, mid-7th century CE. Wall painting; H. 3.4 × W. 11.52 m. Afrasiab Museum. View object page

Photograph by Thorsten Greve © Association pour la sauvegarde de la peinture d’Afrasiab, and Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

Fig. 36 Click to enlarge and scroll through the Northern Wall of the Hall of the Ambassadors. H. 3.4 × W. 11.52 m. Afrasiab Museum. View object page

Photograph by Thorsten Greve © Association pour la sauvegarde de la peinture d’Afrasiab, and Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

Several missing areas do not allow full understanding of the scenes and how they relate to one another. Most vexing is the absent upper part of the western wall, which faces the entrance and is the focal point of the composition. This consists of rows of ambassadors from several different countries converging toward the now-missing image(s) of the ruler (perhaps with his consort) or of a god (and goddess). Painted against a vivid blue background are delegations from China, small Central Asian states, Korea, and possibly, all accompanied by a large number of Turks (identifiable by their long hair and a nearby inscription). This pictorial program might seem fit for a king’s palace, and some still hold that idea. Others, however, note that the size and layout of the hall are actually consistent with the dimensions of aristocratic residences. Regardless, scholars generally agree that this wall painting depicts an actual event that took place in Afrasiab in the mid-7th century, during the reign of Varkhuman. An inscription on the painting mentions this ruler, who is also named in Chinese sources of the period.

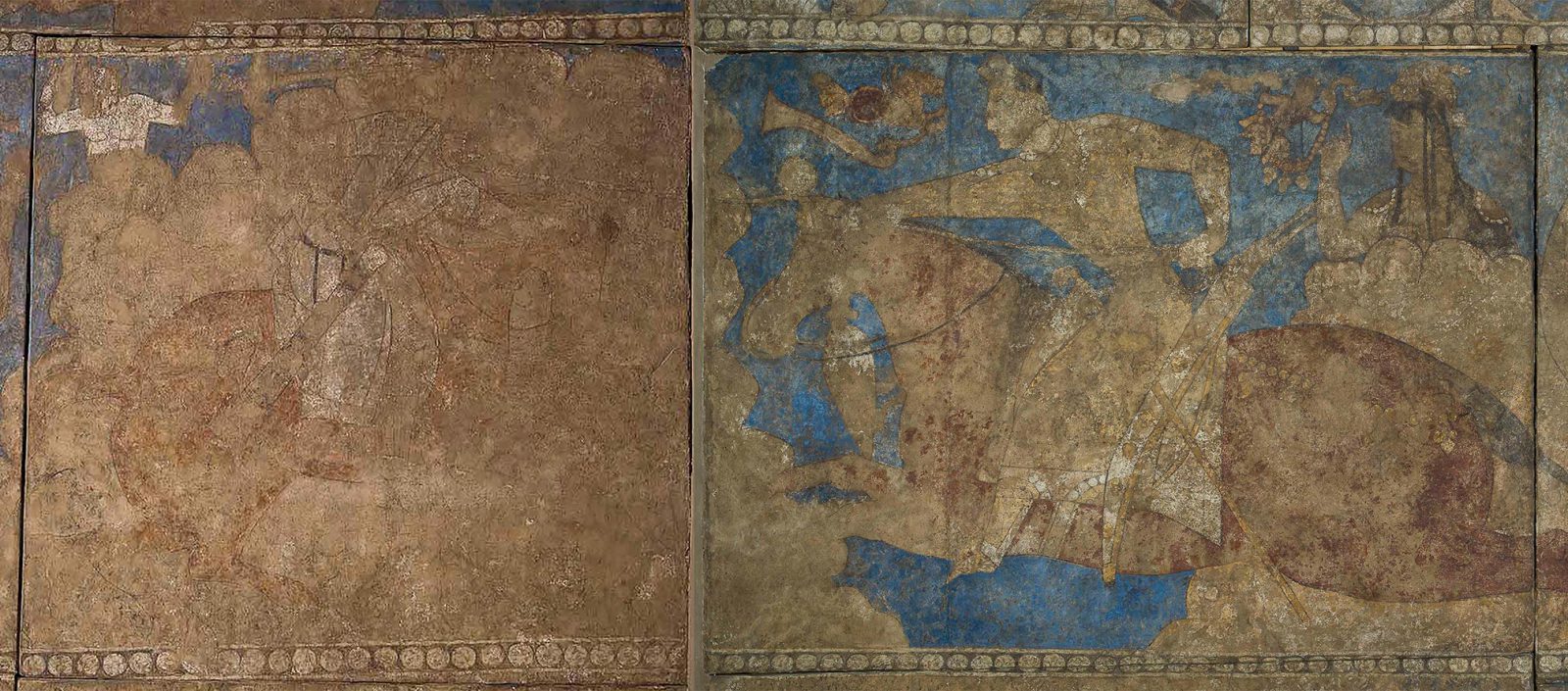

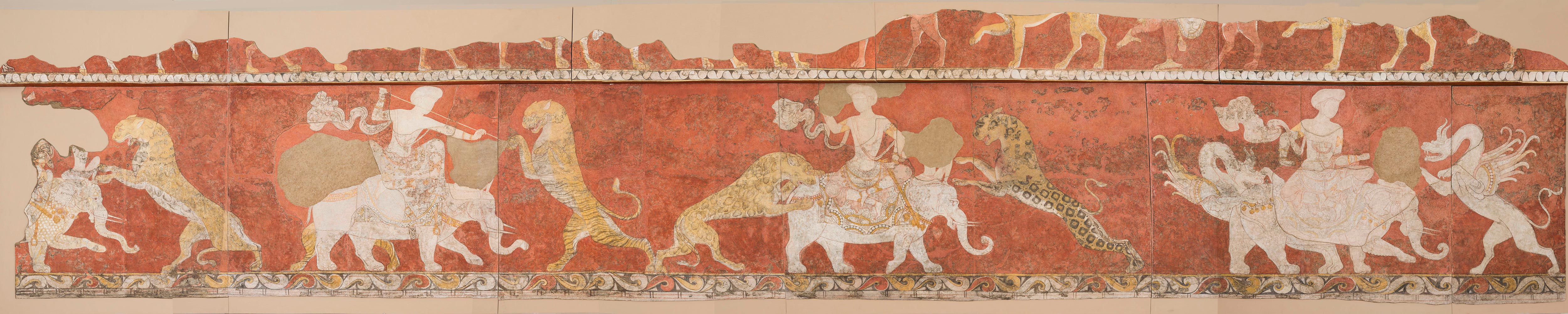

Another major Sogdian artistic program is found at Varakhsha , the fortified country palace of the rulers of the city-state of Bukhara. Of strategic importance as a trade and a crafts center, Varakhsha also served as a contact zone for nomadic groups and the sedentary population of the Bukhara oasis. In the late 7th or early 8th century, one of the Varakhsha Palace’s main rooms, known as the Red Hall, Fig. 39, was decorated with a painted frieze of two registers. Only some of the lower part of the upper one survives, a procession of real and mythological animals, all saddled as mounts of the gods. A sizeable portion of the main frieze has been preserved, though: against a red background, a god sits on an elephant and does battle with various beasts and monsters—sometimes with one, at other times two. This image derives from Hindu iconography, as the deity wears a turban and his elephant mount is that of the leader of the Hindu gods, Indra. Yet, despite these connections with Hinduism and its imagery, it is clear that the artists of Varakhsha had never seen elephants. In addition to the animals’ small proportions, stubby, pawlike legs, and tusks that grow from their lower jaw, they are saddled like horses.

Fig. 39 Click to enlarge and scroll through the Battle between a Deity and Beasts of Prey. Red Hall, Palace at Varakhsha, Uzbekistan (in ancient Sogdiana), late 7th–early 8th century CE. Wall painting; H. 163 × W. 902 cm. The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, SA-14658-14675. View object page

Photograph © The State Hermitage Museum.

The Varakhsha paintings survived well into the Arab invasions of the early 8th century; in fact, some endured into the 730s, when Bukhara was under definitive Muslim rule. We can probably ascribe the earliest ornamental and figural stuccos decorating the Varakhsha Palace to this time period; Figs. 40 and 41.

This form of decoration contrasts with traditional Sogdian decorative media, such as clay. Stucco has not (yet) been found in Sogdian buildings that predate the Muslim invasion. It was, however, a major artistic medium for the Sasanians, so it is likely that stucco came into Sogdiana with the Arabs after their conquest of Persia. Usually carved, but also molded, the Varakhsha stuccos adorning the upper parts of the walls include geometric, floral, and vegetal designs; hunting scenes; and processions of humans, animals, and hybrid creatures.

The Inside Out

The Sogdians’ keen interest in depicting the world around them (evidenced by the Hall of the Ambassadors at Afrasiab) and the mythological and supernatural worlds (in many of the Panjikent paintings just discussed) extended into portraying their own world. They did not, as Frantz Grenet points out, represent their mercantile activities, a major source of their wealth, but instead chose to show their enjoyment of it, such as the scenes of banqueting at Panjikent. In these paintings we see how the Sogdians saw themselves.

Chinese representations of Sogdians caricatured them (especially in grooms, musicians, and others of lower status) as having large noses and round eyes, and being heavy-set and generally comical or “barbaric” in appearance; Fig. 42. In contrast, the Sogdians’ depictions of themselves show people with fine features—the men (unless rulers or nobles) usually clean-shaven, the women oval-faced and sloe-eyed; Fig. 43.

Figs. 44 and 45 Stamp-seal and its impression, with double portrait of a couple and Sogdian inscription naming its owner. 4th–6th century CE. Carnelian; L. 3.3 × W. 2.6 cm, The British Museum, London, 1870.1210.3. View object page

Photograph © Trustees of the British Museum.

Fig. 46 Seal impression of male head with Sogdian inscription, still attached to document it secured, B-4. Mount Mugh, Panjikent (in modern-day Tajikistan), before 722 CE. Unbaked clay with cord of parchment strip. Institute for Oriental Studies of Russian Academy of Sciences, St. Petersburg.

After Wilfried Seipel, Weihrauch und Seide: Alte Kulturen an der Seidenstrasse (Vienna: Kunsthistorisches Museum, 1996), 299, no. 165.

The Sogdians also used another medium for self-representation: stone seals carved in intaglio to be impressed on clay. Like their counterparts in neighboring societies, Sogdian merchants or people of rank would possess at least one seal, which took the place of a signature and both secured and authenticated documents, parcels, cupboards, and doors. Compared to the numerous Sasanian seals that have come down to us, relatively few Sogdian seals have survived—or at least few that can be solidly identified as Sogdian. Of those we have, the most common type of image is the portrait bust of the owner; Figs. 44 and 45. Although these are conventional representations (we cannot speak of “portraiture”), they give us some idea of how Sogdians looked—or thought they looked. One of the documents discovered at Mount Mugh had retained its sealing, Fig. 46, still attached to the leather thong that had secured it, but cut so the recipient could open and read the document. The seal impression shows a bearded man in profile, with short hair combed into a row of curls framing his face, and more curls over his ear and on his neck. He wears an upper garment draped or open at the neck and a spherical drop earring.

Visions of a World Beyond

Many of the traces left by the Sogdians bear witness to their wish for divine protection and a favorable afterlife. Their religious art reflects their diverse religious affiliations, and our knowledge of this comes to us primarily in the forms of wall paintings and clay ossuaries.

In Panjikent, excavations of Temple II yielded a succession of paintings, one painted over the other and representing different phases in the temple’s life. Among them are scenes of mythology and religious ceremonies that include votaries with offerings moving toward an enthroned deity; Fig. 47. This divinity is a four-armed goddess seated on a dragon; in a later version, she sits on a throne supported by dragonlike creatures. Her identification is uncertain, but another version has her seated on a lion and holding the sun in one raised hand and the moon in another. This is the “standard” image of the goddess, who, as the patron of Panjikent, was also represented in private houses on the main wall of the reception room. Other painted deities include Shiva-Weshparkar and Mithra in his chariot, both identified by their attributes; a divine couple with a camel, the symbol of Verethragna-Washagn; and Adhvagh, whose avatar is the elephant, and who is probably the elephant rider in the paintings from Varakhsha already mentioned. A blue-skinned dancing deity, identified as Shiva, has also been found in a different part of Panjikent; Fig. 48.

One cannot discuss the Temple II paintings without mentioning the extraordinary Mourning Scene that covered an entire wall; Fig. 49. Pictured in a domed pavilion, women bend over the deceased, tearing their hair in grief. Outside, men and women mourn by cutting their hair, as well as their faces. Also outside, and to the left of this activity, a large female figure mourns. Her multiple arms (two left arms survive) and the rayed nimbus or halo behind her body and her head signal her divinity. To her side, a kneeling figure, also with a nimbus, extinguishes a torch. Several interpretations of the scene have been offered, but most scholars concur that the large, four-armed figure is the goddess Nana. Generally, Zoroastrians would eschew displays of excessive grief, since they believe it makes the soul’s departure from this world difficult. This is one example of how Mazdaism—the Sogdian religious beliefs and practices based on Zoroastrianism—departed from the “orthodox” form followed by the Sasanian Persians.

The sculpture found in Temple II also deserves notice. Flanking the temple’s inner gate, a painted clay frieze shows elaborately modeled freestanding figures of humans and dragons, as well as sea creatures; Fig. 50. This marine life includes both the real and the fabulous: Hindu makaras, or combinations of land- and sea beasts; Greco-Roman hippocamps, or fish-tailed horses; and human-headed anguipeds whose “legs” are serpents. Such marine imagery seems odd for landlocked Panjikent, but it may refer to an imported myth or a view of an alternate afterlife.

Another means of illustrating one’s wishes for the afterlife was the decoration of ossuaries. In Mazdean funerary practice, after the requisite mourning rituals and exposure of the corpse to carrion beasts or birds (excarnation), the bones would be gathered and placed in a special container or ossuary. This, in turn, would be deposited within a special structure (naos) at some distance from habitation.

The ossuaries are generally made of baked clay (terracotta), with their decoration applied, incised, stamped, or impressed into a mold. Often they are finished with a coat of red slip (watery clay used like paint or glaze); their lids are flat, domed, or pyramidal. Shape, type of decoration, and style vary by region and change over time. Most decoration refers to specific religious beliefs and practices, and includes imagery relating to the afterlife and the soul’s journey to paradise. Thus, on a 7th-or 8th-century ossuary from Mulla Kurgan , near Samarkand, each arch of the arcade covering its rectangular surface contains the figure of a priest, as in Fig. 51. Every side of the pyramidal lid bears three pairs of male and female figures, each carrying a branch and poised beneath a crescent moon and flowerlike star or sun. These six “immortals” may represent the divine Amesha Spentas [“Beneficent Immortals”]. They seem to be dancing, and, if so, they may allude to the pleasures of paradise, a place of music and song.

Fig. 51 Ossuary. Mulla Kurgan (near Samarkand, Uzbekistan), ca. 7th century. Baked clay; 52 × 28 × 69 cm. Samarkand State Museum of History, Art and Architecture. View object page

After Sarah Stewart, ed., The Everlasting Flame: Zoroastrianism in History and Imagination (London and New York: I. B. Tauris, 2013), 100, pl. 36.

Figs. 52–54 Ossuary. Durman Tepe (suburbs of Samarkand, Uzbekistan), Tepe 12, 7th–early 8th century CE. Baked clay, The State Museum of Oriental Art, Moscow, 624 КП [MP] IV–632 КП [MP] IV. View object page

Photograph © The State Museum of Oriental Art, Moscow.

A more complex composition is the subject of a number of ossuaries, known mainly from fragments. These have been found at various localities between Bukhara and Samarkand, and date from the late 6th or early 7th century into the 8th. Individual molds were combined in different orders to embellish all four sides of an ossuary. Lesser craftsmen who re-used and recarved the molds produced ossuaries of lower quality so that in some cases, the details are unreadable. The example shown here from Durman Tepe comes closest to the original stamps to show extraordinary detail; Figs. 52–54. From the time of the first discovery over 100 years ago, arguments have swirled around the identities of the figures. It may be that the figures chosen for a particular ossuary are associated with the afterlife of the deceased whose bones are kept within. Regardless of their precise identities, the art that inspired these figures’ individual appearances—physical characteristics, clothing, and stance—and their placement within an arcade can be traced to Early Christian and Late Roman (Byzantine) sarcophagi and the designs on small metal caskets. Such items and designs were carried eastward by direct import as well as through ivory carvings, Buddhist reliquaries, and other portable objects that made their way from Afghanistan and Northwest India to Sogdian Central Asia.

A last example is an ossuary from the Shahr-i Sabz Oasis (Sogdian Kesh, south of Samarkand); Fig. 55. One of several that illustrate the soul’s journey to paradise, its surface is covered with two registers of stamped figures in low relief, each illustrating a particular phase of the journey. Thus, the ossuaries make tangible the complex eschatology of Sogdian religion: that is, the death, judgment, and final destiny of each individual soul. Just as these three examples of Sogdian funerary art illustrate a wide range of styles and iconography, so do the paintings, sculpture, and metalwork of Sogdian artists and artisans capture the richness and diversity of the Sogdian worldview. It is due to these surviving works of art that we are able to experience the vibrancy of Sogdian life and imagination.

Adapted from Nicholas Sims-Williams, trans., “The Sogdian Fragments of the British Library,” Indo-Iranian Journal 18, no. 1–2 (1976): 56–57.

Boris I. Marshak [Marschak/Maršak], Legends, Tales, and Fables in the Art of Sogdiana (New York: Bibliotheca Persia Press, 2002), 25–54.

Boris I. Marshak [Marschak/Maršak], “Remarks on the Murals of the Ambassadors Hall,” Rivista degli Studi Orientali 78, supp. no. 1: Royal Naurūz in Samarkand: Proceedings of the Conference held in Venice on the Pre-Islamic Paintings at Afrasiab (2006): 75–85, esp. 75.

Aleksandr Naymark [Naimark], “Returning to Varakhsha,” The Silk Road Foundation Newsletter 1, no. 2 (2003). Available online: http://www.silkroadfoundation.org/newsletter/december/varakhsha.htm

Frantz Grenet, “The Self-Image of the Sogdians,” in Étienne de la Vaissière and Éric Trombert, eds., Les Sogdiens en Chine (Paris: École français d’Etrême-Orient, 2005), 123–40.

See Frantz Grenet and Étienne de la Vaissière, “The Last Days of Panjikent,” Silk Road Art and Archaeology 8 (2002): 155–96; and Boris I. Marshak [Marschak/Maršak], “On the Iconography of Ossuaries from Biya-Naiman,” Silk Road Art and Archaeology 4 (1995 [1996]): 308.

Amriddin E. Berdimuradov, Gennadii Bogomolov, Margot Daeppen, and Nabi Khushvaktov, “New Discovery of Stamped Ossuaries near Shahr-i Sabz (Uzbekistan),” Bulletin of the Asia Institute, n.s. vol. 22 (2008 [2012]): 137–43.