1862 (Budapest, Hungary)—1943 (Kabul, Afganistan).

Photograph by Thompson, The Grosvenor Studios, 1909. Photograph © Wellcome Collection, V 27218

Marc Aurel Stein

by Matthew Z. Dischner

Marc Aurel Stein would become quite likely “the most prodigious combination of scholar, explorer, archaeologist and geographer of his generation.” His wide-ranging interests took him to India, Iran, and Iraq, but he is best remembered for his explorations and discoveries of Silk Road sites in the bleakest regions of Chinese Turkestan (now Xinjiang ) and at Dunhuang . A talented linguist, Stein had mastered Greek, Latin, French, and English while still in his teens (he spoke Hungarian and German at home) and did his advanced studies at the Universities of Vienna, Leipzig, and Tübingen. It was from the last that in 1883 he received his PhD in Indology and Old Iranian. The next year found him in England, where he pursued his studies in “oriental” languages and in archaeology. His linguistic skills, along with mapmaking learned during military service in Hungary, suited him well for his future adventures in Central Asia.

In 1904 Stein became a British citizen. He went to India in 1887 to be Registrar of the University of the Punjab. The following year he became Principal of Oriental College, Lahore, until 1899. This afforded the time and setting in which to gain greater familiarity with the travels (and particularly the routes) of Alexander the Great through Iran and India, and of the Chinese Buddhist pilgrim Xuanzang 玄奘, into Central Asia. The British had become interested in what was then known as Chinese Turkestan, since Russia and Germany were vying for influence in the region. Even though the “Great Game” that Britain played with Russia over Afghanistan and neighboring territories had largely ended by 1895, Stein cleverly capitalized on his adopted country’s sense of competition and obtained funding for his expedition. Thus, in 1900, Stein left the comfort of Kashmir to retrace a part of Xuanzang’s journey and explore the route to Khotan , along the southern route of the Silk Road. There, in the past, Iranian, Indian, and Chinese cultures had met. This would be the first of his four archaeological, geographical, and ethnological expeditions to Turkestan or eastern Central Asia.

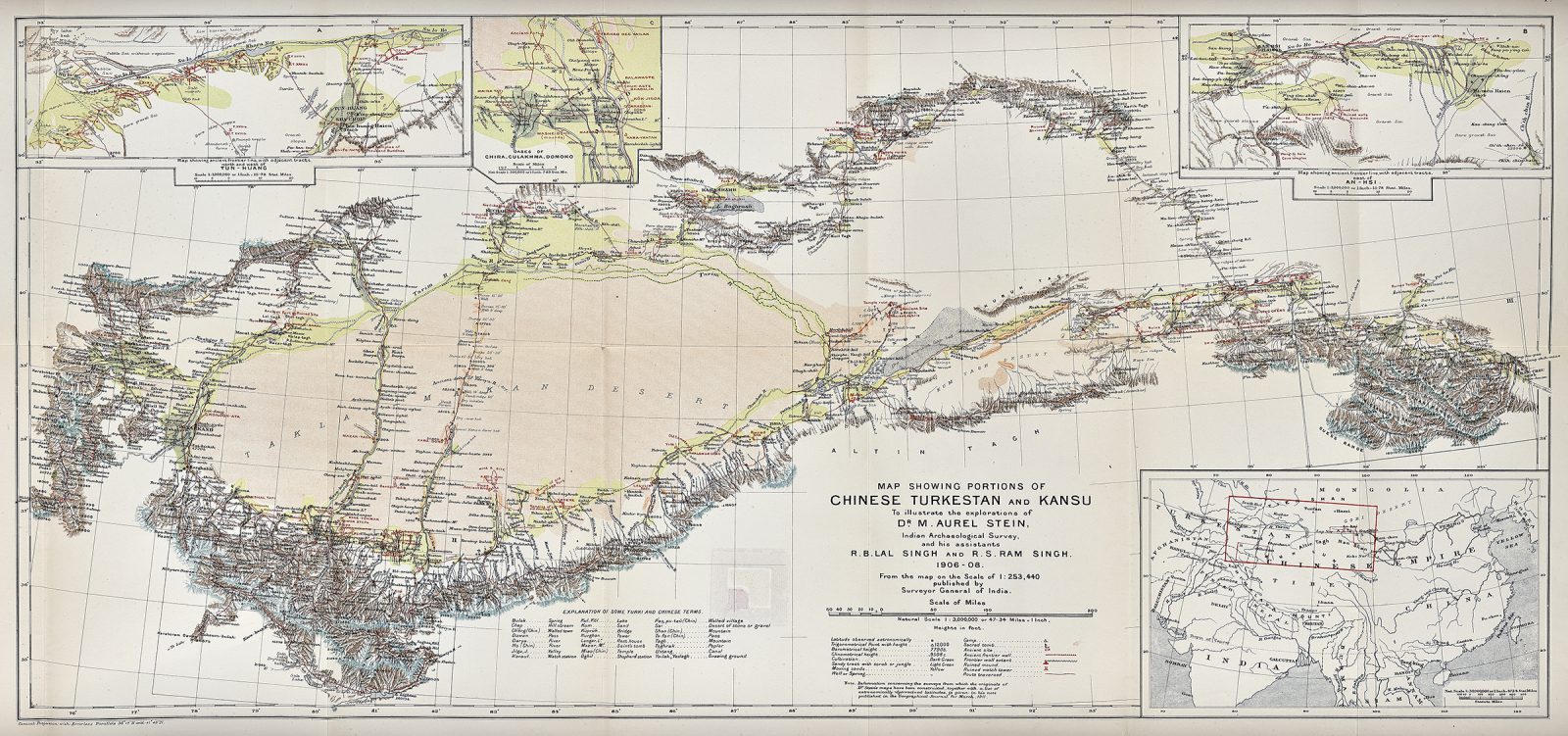

Fig. 1. Map of the Second Central Asian Expedition by Stein (1906–8). Map made with assistance of Stein’s Indian surveyors, Rai Bahadur Lal Singh and Naik Ram Singh. Red line indicates the route followed; archaeological sites are also shown in red.

Photograph © Library of Hungarian Academy of Sciences, LHAS 717.918.

Stein’s second expedition (1906–8) is one of particular relevance to the study of the Sogdians; Fig. 1. He traveled, mostly on foot, between Lahore (in present-day Pakistan) and Dunhuang , in the northwestern Chinese province of Gansu, where the northern and southern Silk Roads converge after circling the Taklamakan Desert ; Fig. 2.

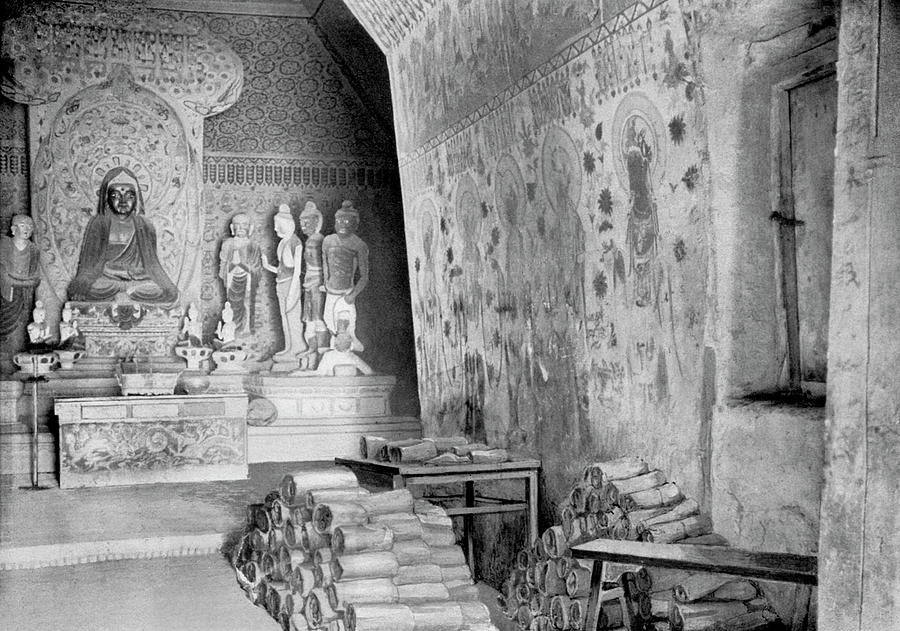

Among the many Buddhist caves near Dunhuang are the Mogao Grottoes , also known as the Qianfodong, or “Caves of the Thousand Buddhas.” Stein had learned of a recent discovery there: a small cave (No. 17), hidden for 900 years, filled with manuscripts in several languages; Figs. 3–5.

Fig. 3. Aurel Stein’s view of Mogao Cave 16, in Dunhuang 敦煌, Gansu Province 甘肅省, China, with a number of manuscripts from Cave 17 bundled on the floor.

After Aurel Stein, Serindia: Detailed report of explorations in Central Asia and westernmost China (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1932), vol. 2, fig. 200.

Fig. 4. Manuscripts in Qianfodong 千佛洞 (Cave of a Thousand Buddhas) at Dunhuang. The Library Cave contained some 15 cubic meters of manuscripts and paintings, dating from 406–1002 CE. Religious texts are mostly Buddhist, but include Manichean, Nestorian Christian, Daoist, and Confucian works. Secular documents offer glimpses of everyday life as well. The cave was likely sealed to protect records from invaders.

Photograph © Library of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Stein LHAS Photo 13/1 (56).

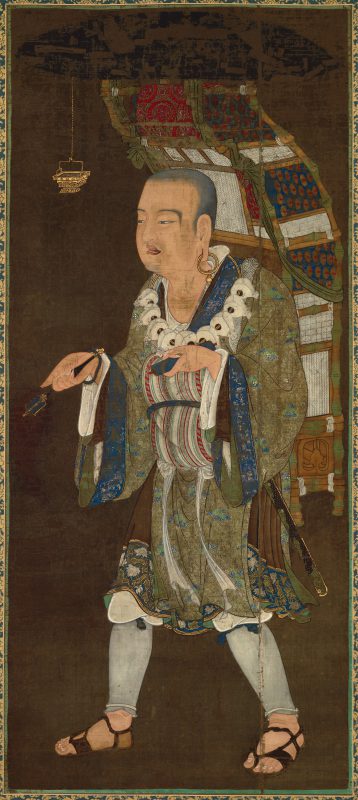

Fig. 6. Painting of Chinese monk Xuanzang 玄奘, also called Tang Seng 唐僧, on his quest to India to obtain Buddhist sutras. Born in 602 CE in Luoyang 落陽市, Henan Province 河南省, China, he died in 664 CE in Chang’an 長安市, now Xi’an 西安市, in Shaanxi Province 陝西省.

Image “Xuanzang w” by Alexcn is released to public domain.

Stein expressed his admiration for the great Buddhist scholar-monk Xuanzang Fig. 6 to a certain Taoist monk who was the self-appointed guardian of Dunhuang. Having unsuccessfully sought funds from local officials to restore the caves, the monk agreed to sell Stein the many thousands of religious and secular manuscripts, as well as paintings and textiles. Among them were a printed copy of the Diamond Sutra, dating to 868 and the oldest printed text known, and documents written in Sogdian, Tibetan, Sanskrit, and Khotanese, among other languages.

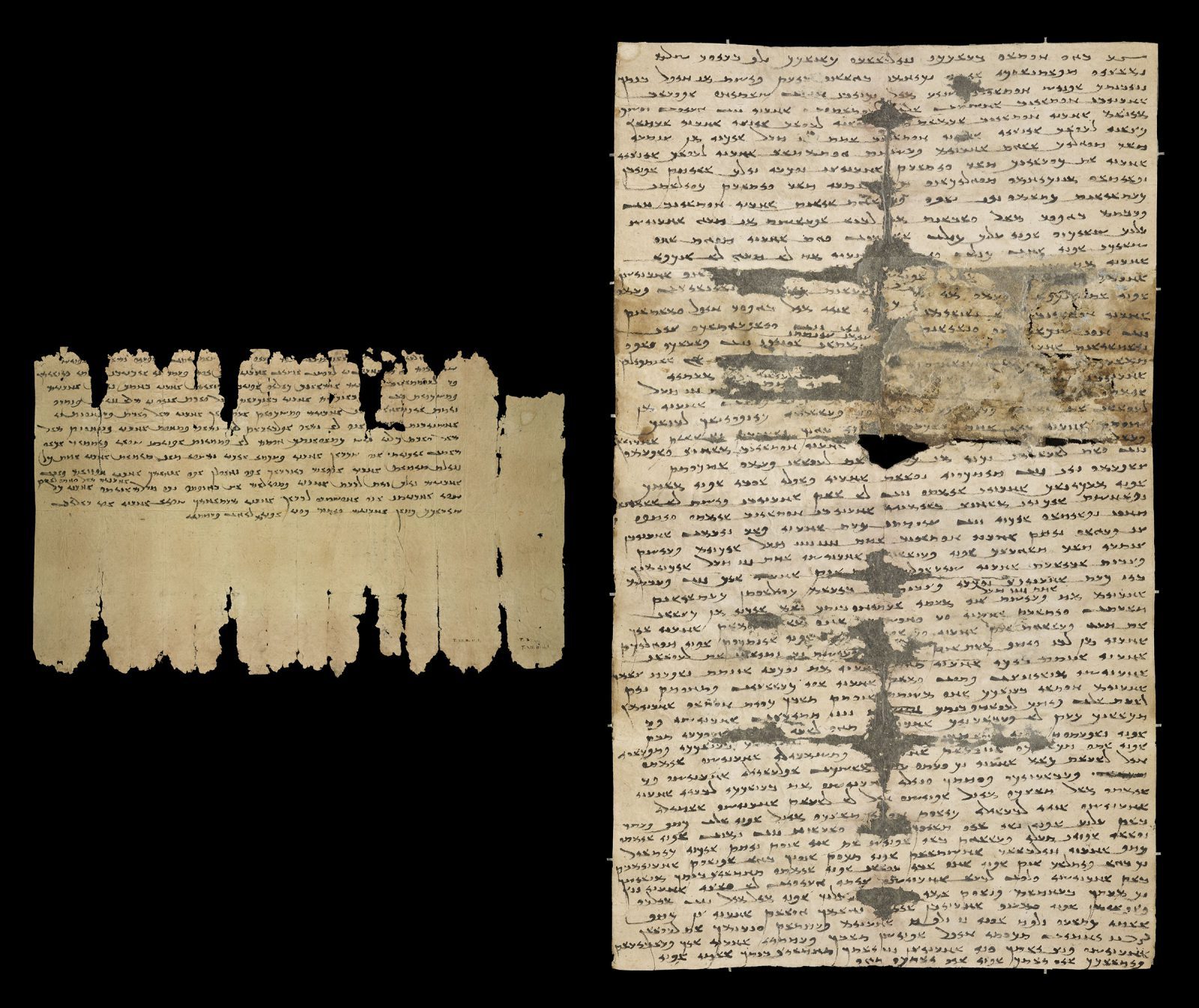

Another spectacular find that Stein made was pure chance. While exploring an area some ninety kilometers west of Dunhuang, he and his team stumbled across an abandoned mailbag in a ruined watchtower ; Fig. 7.

Fig. 7. Ruins of an ancient watchtower near Dunhuang, in Gansu Province, Western China. It was in the ruins of a tower such as this that Sir Aurel Stein found the mail pouch containing the Sogdian Ancient Letters.

“Summer Vacation 2007, 263, Watchtower In the Morning Light, Dunhuang, Gansu Province” by The Real Bear is licensed under CC BY 2.0. https://flic.kr/p/4onCCH.

Preserved by the arid climate and the shelter provided by the ruins, the mailbag and its contents—five nearly complete letters written in Sogdian from Sogdians living in different parts of China. These have proved invaluable for our understanding of various dimensions of Sogdian trade and culture. Datable to 313–14 CE, they are the earliest substantial examples of Sogdian writing and provide insights into the lives of these “expatriates” and the turbulent events in China at the time. Although Stein could not recognize the content of the ancient letters, he knew they were significant; Fig. 8.

Fig. 8. Sogdian Ancient Letters 1 and 2, rectos, 312 or 313 CE. Ink on paper; H. 42 × W. 24.3 cm. View object page

Photograph © The British Library, Or. 8212/92 and Or. 8212/95.

Stein was an avid and meticulous writer. Despite the punishing cold of the desert, each night he recorded the day’s activities in his neat copperplate script. His massive Ruins of Desert Cathay is his detailed narrative of the entire journey. Aided by a talented group of Sikh guides, Stein passed through areas that even now are considered dangerous. On a number of occasions he narrowly avoided avalanches, crossing mountain passes at midnight to ensure the snow stayed cold and frozen. In this and other expeditions, Stein was accompanied by a dog—rather, a series of dogs, each of whom he named Dash; Fig. 9.

Fig. 9. Group with Stein and assistants at Ulugh-Mazar (north of Chira, in Xinjiang, now China). Left to right, seated: Jiang Xiaowang, Stein with his dog Dash, Rai Bahadur Lal Singh. Standing: Ibrahim Beg, Jaswant Singh, Naik Ram Singh.

Photograph © Library of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Stein LHAS Photo 37/5 (79).

Despite the impact of his discoveries, Stein was never much concerned with the Sogdians. His expeditions never took him through the heartland of Sogdiana, and his encounters with their material culture were incidental. Their paths crossed because Stein sought out the same places that Sogdian traders had sought out centuries before.

In 1943 Stein died at age eighty-one in Kabul, one week after arrival and in the midst of planning for an Afghan expedition. In 1932, Freya Stark (1893–1993), herself an intrepid explorer and accomplished linguist, had described Stein as “a little gnome of a man with apple cheeks and the eyes of youth.” His unwavering enthusiasm for Central Asia was inspiring then and has inspired countless researchers since.

To read more on Stein and see a number of images and maps from his expeditions, visit http://stein.mtak.hu/index-en.html and http://dunhuang.mtak.hu/index-en.html. These two Hungarian websites explore the relationship between Hungarian explorers and Asia, shown mainly through the lens of Sir Aurel Stein.

Owen Latimore, quoted in Jeannette Mirsky, Sir Aurel Stein: Archaeological Explorer, New ed. (paperback); original ed. 1977 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998), ix.

Marc Aurel Stein, Ruins of Desert Cathay: Personal narrative of explorations in Central Asia and westernmost China, 2 vols. (London: Macmillan, 1912).

Jeannette Mirsky in Marc Aurel Stein, On Central-Asian Tracks: Brief Narrative of Three Expeditions in Innermost Asia and Northwestern China, reprint with introduction by Jeannette Mirsky (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1964), ix.

Map of the Second Central Asian Expedition by Stein (1906–8). Map made with assistance of Stein’s Indian surveyors, Rai Bahadur Lal Singh and Naik Ram Singh. Red line indicates the route followed; archaeological sites are also shown in red.

Photograph © Library of Hungarian Academy of Sciences, LHAS 717.918.

The march across high dunes in the Taklamakan Desert, toward the end of the Keriya River. Oriental Collection, Stein LHAS Photo 12/1 (10).

Photograph © Library of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences.

Aurel Stein’s view of Mogao Cave 16, in Dunhuang 敦煌, Gansu Province 甘肅省, China, with a number of manuscripts from Cave 17 bundled on the floor.

After Aurel Stein, Serindia: Detailed report of explorations in Central Asia and westernmost China (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1932), vol. 2, fig. 200.

Manuscripts in Qianfodong 千佛洞 (Cave of a Thousand Buddhas) at Dunhuang. The Library Cave contained some 15 cubic meters of manuscripts and paintings, dating from 406–1002 CE. Religious texts are mostly Buddhist, but include Manichean, Nestorian Christian, Daoist, and Confucian works. Secular documents offer glimpses of everyday life as well. The cave was likely sealed to protect records from invaders.

Photograph © Library of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Stein LHAS Photo 13/1 (56).

Paul Pelliot examining manuscripts in Library Cave (Cave 17) at Dunhuang in 1908, a year after Stein’s expedition.

Charles Nouette Grotte 163. Niche aux manuscrits. Photograph © Musée Guimet, archives photographiques, AP8186.

Painting of Chinese monk Xuanzang 玄奘, also called Tang Seng 唐僧, on his quest to India to obtain Buddhist sutras. Born in 602 CE in Luoyang 落陽市, Henan Province 河南省, China, he died in 664 CE in Chang’an 長安市, now Xi’an 西安市, in Shaanxi Province 陝西省.

Image “Xuanzang w” by Alexcn is released to public domain.

Ruins of an ancient watchtower near Dunhuang, in Gansu Province, Western China. It was in the ruins of a tower such as this that Sir Aurel Stein found the mail pouch containing the Sogdian Ancient Letters.

“Summer Vacation 2007, 263, Watchtower In the Morning Light, Dunhuang, Gansu Province” by The Real Bear is licensed under CC BY 2.0. https://flic.kr/p/4onCCH.

Sogdian Ancient Letters 1 and 2, rectos, 312 or 313 CE. Ink on paper; H. 42 × W. 24.3 cm.

Photograph © The British Library, Or. 8212/92 and Or. 8212/95.

Group with Stein and assistants at Ulugh-Mazar (north of Chira, in Xinjiang, now China). Left to right, seated: Jiang Xiaowang, Stein with his dog Dash, Rai Bahadur Lal Singh. Standing: Ibrahim Beg, Jaswant Singh, Naik Ram Singh.

Photograph © Library of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Stein LHAS Photo 37/5 (79).