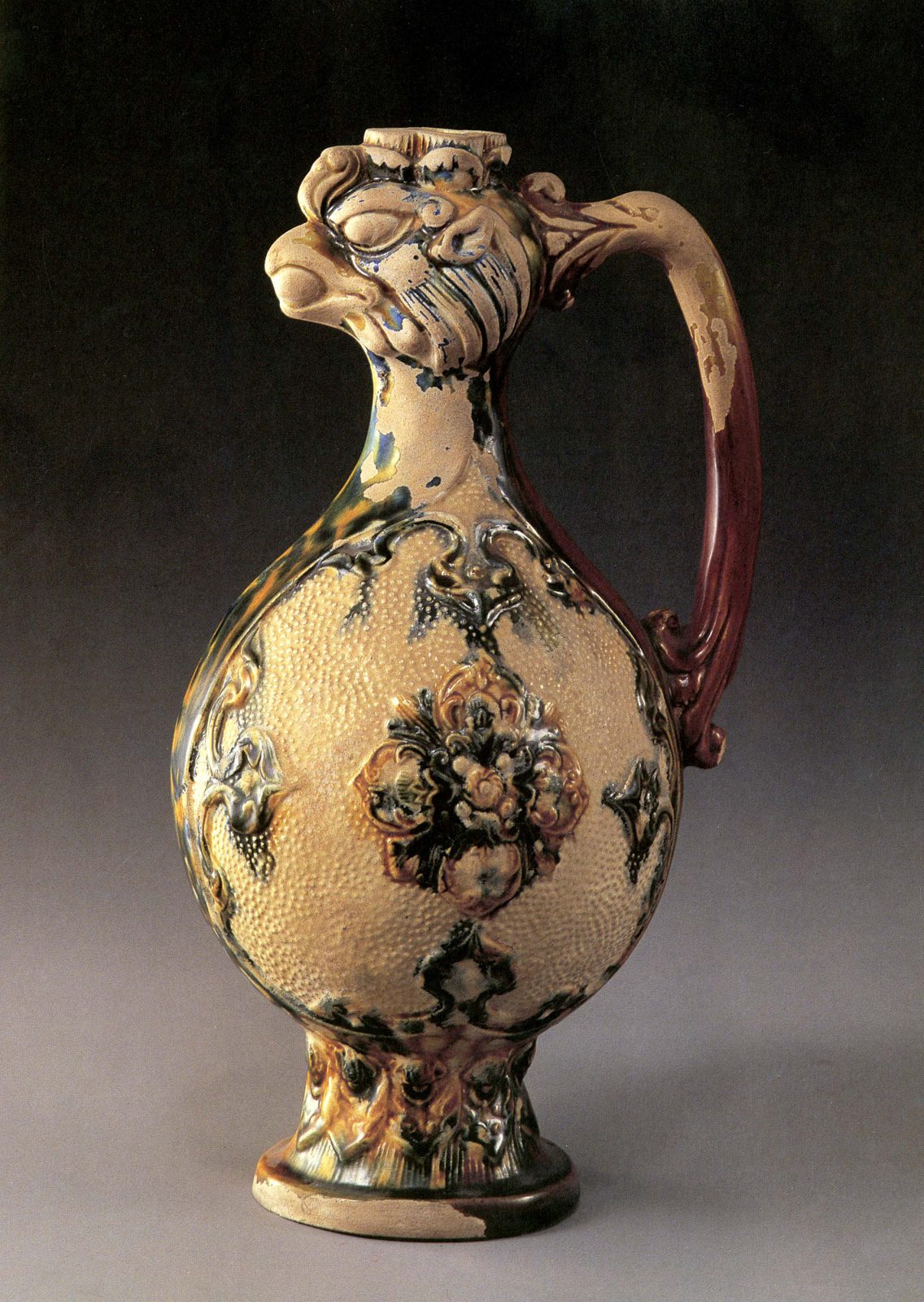

Winged Camel Ewer

Sogdian, late 7th–beginning of 8th century CE

Silver with gilding, Khwarezmian inscription on base, indicating weight; H. 40 cm

Found in 1878, Mal’tsevo, Perm Province, Russia ; ex–S. G. Stroganov Collection, SPb; acquired by The State Hermitage in 1925

The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Inv. No. S-11.

Photograph © The State Hermitage Museum

Made to hold and pour water or wine, this pear-shaped gilt silver ewer is adorned on each side by an extravagantly winged Bactrian camel enclosed within a rope-bordered medallion. The remaining surface of the ewer’s body, along with its neck and base, are engraved with floral and foliate designs on a ring-punched ground. The vessel’s sinuous handle is attached to its neck by a leafy form that issues from the mouth of a dragon’s head that marks the uppermost curve of the ewer’s handle; Fig. 1.

Its overall shape and decoration with a single creature in a medallion recall certain ewers manufactured in Sasanian Persia in the late 6th and early 7th centuries; Fig. 2. Yet closer inspection reveals some notable differences in the Sogdian vessel:

- There is greater dynamism in the representation of the animal, especially in the depiction of its wing. Unlike those of the fantastic beasts that adorn many Sasanian ewers, the camel’s wing feathers are not static and clustered together; rather, each long feather seems to writhe with a life of its own.

- The allover patterning of the ewer’s background is not found in Sasanian metalwork, although it is a characteristic of many Chinese silver works of the Tang period.

- Most revealing, however, is the attachment of the handle to the ewer’s neck instead of to its shoulder. It is this type of ewer—the Sogdian, not the Sasanian—that appears in the banquet scenes on some of the Sino-Sogdian funerary furnishings, such as those of An Qie and Wirkak.

Fig. 3 Judith A. Lerner (Institute for the Study of the Ancient World, New York University) talks about her favorite Sogdian object, the Winged Camel Ewer.

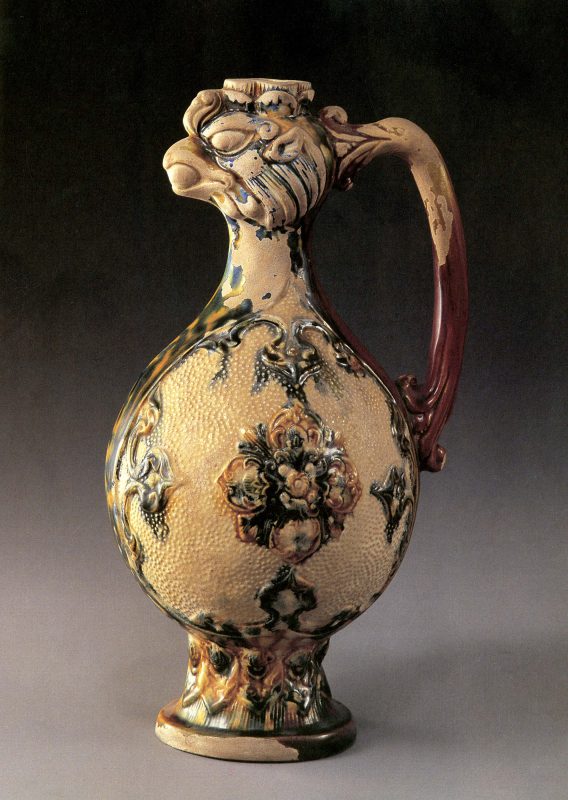

Fig. 4 Phoenix-Headed Ewer. Tang dynasty (618–906 CE), from a Tang tomb. Polychrome lead glazes over buff earthenware with molded relief decoration. H: 31 cm. Gansu Provincial Museum, Lanzhou 兰州.

After Annette L. Juliano and Judith A. Lerner, Monks and Merchants: Silk Road Treasures from Northwest China (New York: Harry N. Abrams and Asia Society Museum, 2001), 316, no. 111.

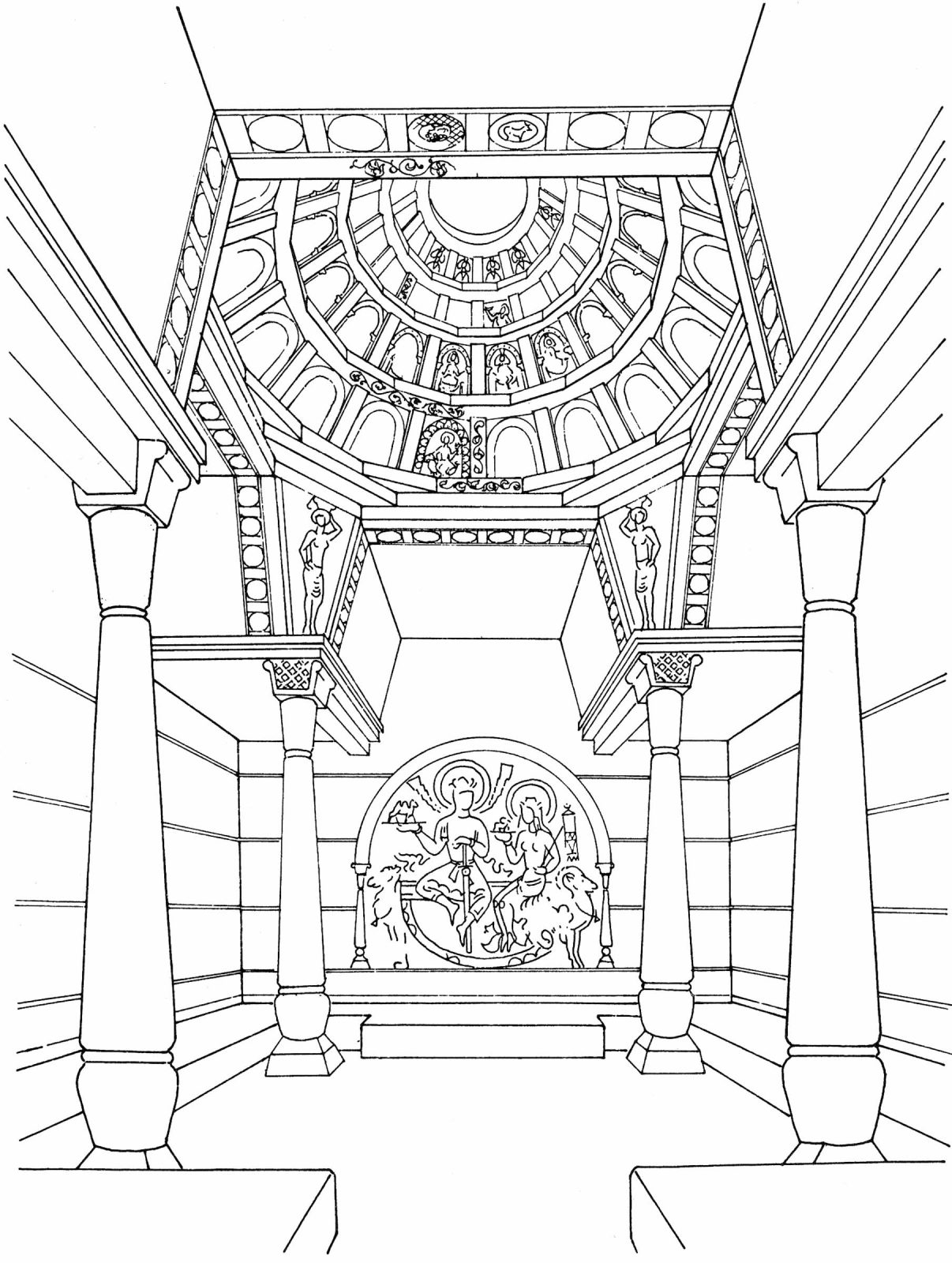

Such examples of Sogdian metalwork entered China through trade or as diplomatic gifts; once there, they inspired Chinese craftsmen. The vessel’s shape and decoration—a figured medallion in relief on an ornamented background—were imitated in Tang-period metalwork and ceramics. A number of glazed ceramic ewers with phoenix-head spouts have been found in 7th- and 8th-century Tang tombs and reveal their debt to the Sogdian ewer type: a high foot, flattened bulbous body, slender neck, and an elongated handle attached to the back of a phoenix head; Fig. 4.

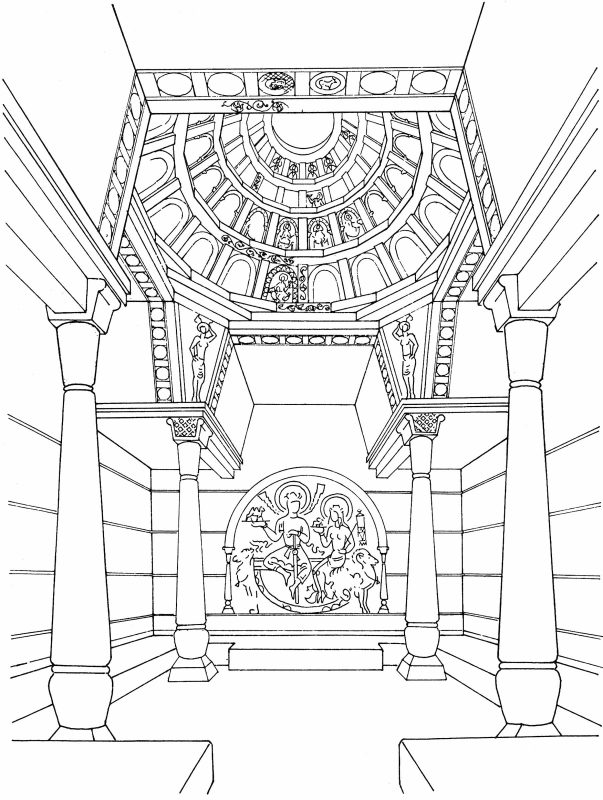

It is not surprising that a winged camel decorates this particular ewer. As the prime movers of the overland caravan trade, the Sogdians had a special relationship with the god of victory, Verethragna (Sogdian: Wasagn or Washagn), whose functions included serving as patron of travelers. One of his avatars was the two-humped Bactrian camel, which often appeared winged, as on the ewer. On the main wall of a well-to-do house in Panjikent, a male and a female deity sit on a bench-throne with animal-shaped supports; Fig. 5. The support on his side is a camel, while that on her side is a ram. Each holds a plate on which stands the figure of an avatar—his a Bactrian camel, hers a ram. Most likely, they are the camel-god Wasagn and his consort, Wannanc/Wannanch, who were probably the patrons of the family that occupied that house.

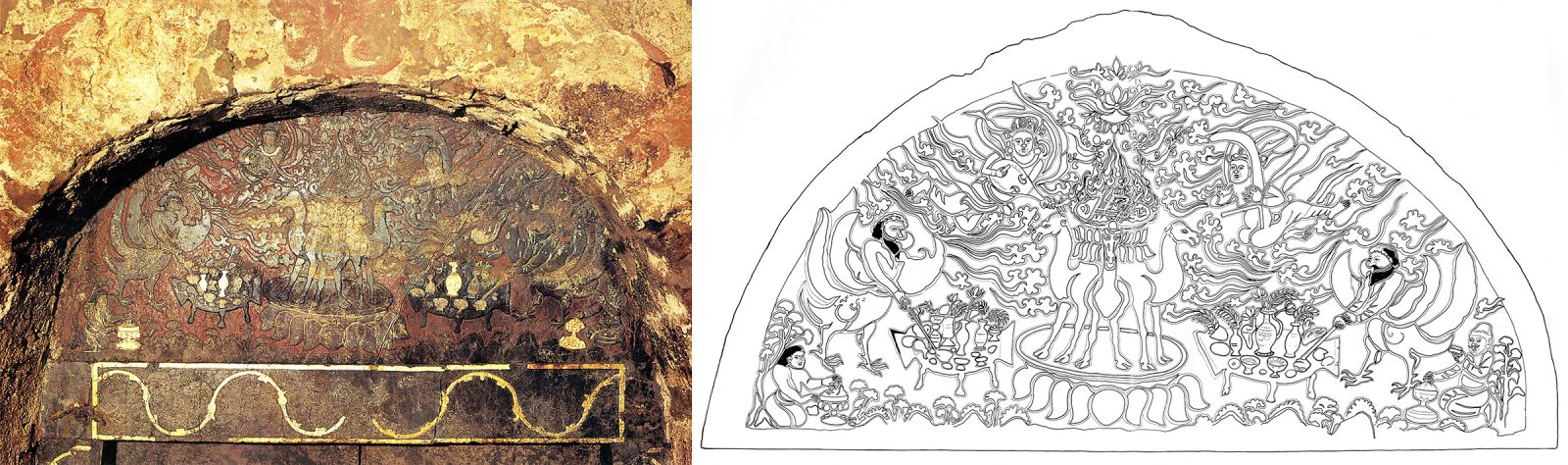

Wasagn was worshipped by at least some Sogdians living in China. An Qie, whose Chinese surname, An, indicates that his family came from Bukhara, had ordered a painting above the door to his burial chamber that shows the sacred fire of Mazdaism, supported by the foreparts of three camels; Fig. 6.

To each side, a birdman wearing a mouth-covering, or padam, perform the Afrinagan ceremony to praise the god Ahura Mazda, while at the lower edges of the composition An Qie and his son kneel before small fire holders.

by Judith A. Lerner