The (Re)discovery of the Sogdians

From Ancient Texts to 3D Scanning

by Judith A. Lerner with Matthew Z. Dischner

The almond groves of Samarcand,

Bokhara, where red lilies blow,

And Oxus, by whose yellow sand

The grave white-turbaned merchants go.

—Oscar Wilde, “Ave Imperatrix” (1881)

Oscar Wilde’s poem of the late 19th century offers a quintessential western image of the imagined “East”—a heady brew of evocative names, bright colors, and exotic dress. Such an image was the product of a romantic mind, driven by ignorance and distance as much as knowledge; Oscar Wilde never traveled to Central Asia and most likely never met a white-turbaned merchant, grave or otherwise. Those few Westerners who had first-hand knowledge of Central Asia in the 19th century were a mixed bag of explorers, diplomats, government officials, and military officers. Many of them were players in the “Great Game” that pitted the Russian and British empires against each other for influence and control of the borderlands dividing them. Even if some had an interest in history, their knowledge was primarily military and sociopolitical, focused on their own present rather than the ancient past.

Western knowledge of ancient Central Asia, and of the Sogdians in particular, was thus extremely limited in the times of Oscar Wilde. Classical scholars with good memories might remember a reference to the Sogdians in Book Three of Herodotus’s Histories. Perhaps they had read the scattered references to Sogdiana in works by the classical geographers Ptolemy and Strabo, or by historians Arrian and Quintus Curtius. Scholars and practitioners of Zoroastrianism would have known the name of Sogdiana from the Avesta (a collection of Zoroastrian sacred texts), in which the region is listed as the second of sixteen “Great Districts” created by the supreme deity, Ahura Mazda. Scholars of “oriental” languages might also have read of Sogdia as a subject land of the Achaemenid king Darius the Great, as mentioned in Darius’s inscription on Mount Bisitun in northwestern Iran, which Colonel Henry C. Rawlinson translated in 1848. Yet these were brief, tantalizing references, with little insight about the lived experience of Sogdian history.

It is remarkable to think how different things are today. Over the last 120 years the Sogdians have become increasingly understood as a culture of major influence and import. Their history, archaeology, and language figure in university courses and are topics of significant scholarly interest. We now know the Sogdians were a people of great mercantile, agricultural, and artistic ability, who played crucial roles in the exchange of goods and ideas between China and other parts of Asia. While doing so, they also produced their own unique culture in their homelands around Bukhara and Samarkand , in present-day Uzbekistan. This essay briefly tells the story of this discovery of the Sogdians—or “rediscovery,” as perhaps we should more accurately describe it.

Surviving Textual Sources on the Sogdians

We use the term rediscovery because there has long existed a rich range of sources offering detailed historical and cultural information on Sogdiana and the Sogdians. In fact, it stretches back almost two thousand years and runs through medieval times. The issue for Western scholars was that this information was recorded in languages and texts that were little read or largely inaccessible: accounts by medieval Arab and Persian historians and geographers, official Chinese dynastic annals, and Chinese travelers’ reports Xuanzang Learn more about the Chinese Buddhist traveler Xuanzang. From such sources we now glean valuable knowledge about some of the Sogdian city-states and their rulers, specific historical events involving them, and Sogdian customs and religious rites.

Xuanzang Learn more about the Chinese Buddhist traveler Xuanzang. From such sources we now glean valuable knowledge about some of the Sogdian city-states and their rulers, specific historical events involving them, and Sogdian customs and religious rites.

In contrast with those in the West, Chinese scholars were well acquainted with the Sute ren 粟特人—Chinese for Sogdians—because Sogdian place names, geographic descriptions, and historical events were abundantly recorded in Chinese dynastic histories and other writing. Such dynastic chronicles helped illuminate the period from Alexander’s brief rule in the late 4th century BCE into the Tang dynasty and the 9th century CE. From as early as about 116 BCE, with the Shiji 史記 [Records of the Grand Historian], Chinese sources mention the Sogdians as sending tribute, although the actual name used for their country or region is ambiguous. Nevertheless, from this time on, Chinese historical records and accounts describe Sogdian cities and regions, often in detail. These records also reflect establishment of a Sogdian trading network as early as the 4th century CE, as well as the influx of Sogdian émigrés into China. Many of these immigrants received Chinese surnames to reflect their origins in “the Western RegionsThe Nine Sogdian Surnames Learn more about the Chinese names for Sogdian families in China,” the Chinese designation for Sogdiana and other Central Asian areas. Even after the disastrous rebellion of the half-Sogdian general An Lushan in 750 and well into the Song period (960–1279), echoes of Sogdian immigrants persisted in Chinese culture. Among the most long-lived of these was the image of the dancing Sogdian; Figs. 1–3.

Fig. 1 Dancing Central Asian. From vicinity of Shandan, Gansu province, China, 7th century CE. Partly gilt bronze; H. 13.7 × W. 8 cm. Shandan Municipal Museum, China. View object page

Image after Annette L. Juliano and Judith A. Lerner, Monks and Merchants, (New York: Harry N. Abrams with the Asia Society, 2001), 255, cat. 82.

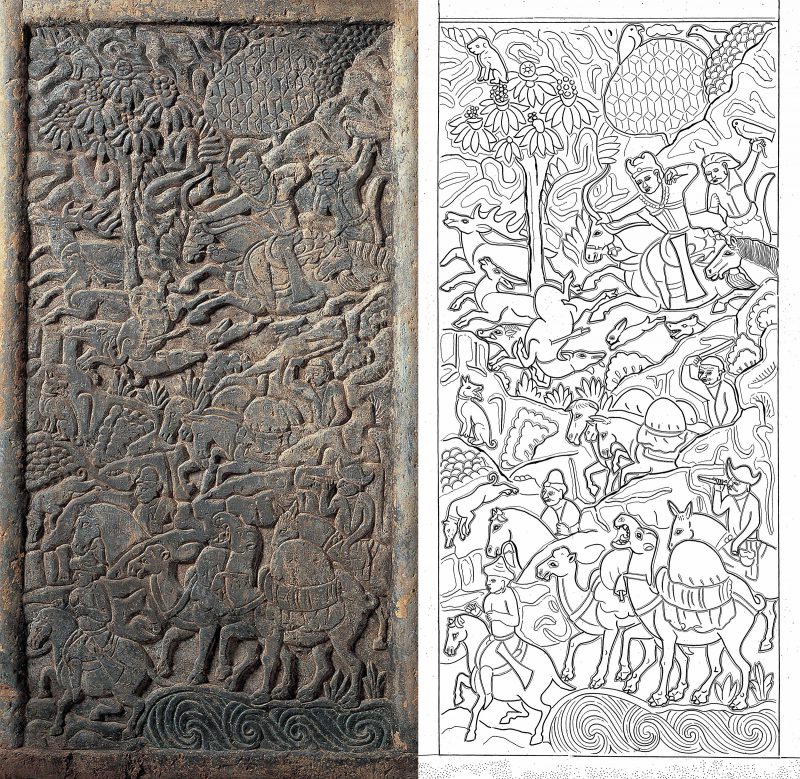

Fig. 2 Two Tomb Doors. From Tomb M6 of the He family cemetery at Yanchi 盐池县, Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region 宁夏回族自治区, China, Tang dynasty (618–907 CE), ca. 700 CE. Gray stone; H. 89 × W. 43 cm. Ningxia Hui Autonomous Regional Museum, Yinchuan 宁夏回族自治区博物馆,银川市.

After Juliano and Lerner, Monks and Merchants, 251, cat. 81.

Fig. 3 Tile with Image of a Central Asian Dancer. China, Xiuding Si 修定寺, Anyang 安陽, Henan Province, Tang dynasty (618–907 CE). Molded earthenware; H. 54.6 × W. 48.3 × D. 9.5 cm. Asian Art Museum of San Francisco, The Avery Brundage Collection, B60S74+ View object page

© Asian Art Museum of San Francisco.

Another valuable Chinese source is the Hou Han Shu 後漢書 [History of the Later Han], compiled in the mid-5th century. The chapter on the kingdom of “Liyi” 栗弋 (correctly, Suyi 粟弋) or Sogdiana, is described thus: “a dependency of Kangju 康居 [a federation of tribes in the Talas Basin, Tashkent , and Sogdiana]. It produces famous horses, cattle, sheep, grapes, and all sorts of fruit. The water and soil of this country are excellent, which is why its grape wine is so famous.” Such sources have to be read carefully, however, since their information can mislead. For example, Sogdian colonial expansion to the north for purposes of trade had led the Chinese Buddhist pilgrim Xuanzang in the mid-7th century to define Sogdiana as the entire region stretching from the Ozero Issyk-Kul Озеро Иссык-Куль [lit., “hot lake”] in eastern Kyrgyzstan to the river Oxus, or Amu Darya —a much larger area than Sogdiana’s true geographic reach.

If knowledge of Sogdian interactions with China survived enshrined in Chinese historical sources, the Muslim sources that survived offered a different perspective. Largely written some centuries after the Muslim takeover of Sogdiana, they are copies of now-vanished earlier writings, almost contemporary with that event. Their focus is more on the Islamic conquests in Central Asia; thus, events and personages are viewed through the lens of the Sogdians’ conquerors. Nonetheless, an essential source for information on Sogdiana is the Persian historian Abu Jaʿfar Muhammad ibn Jarir al-Tabari (839–923). Written in Arabic, his chronicle Tarikh al-Rusul wa al-Muluk تاريخ الرسل والملوك [History of the Prophets and Kings, often called the Tarikh al-Tabari], is a universal history beginning with the Creation and concluding with events of 915 CE. Tabari draws on earlier works, such as eyewitness accounts and local chronicles no longer available to us, to include different versions of the same event with different interpretations and perspectives—a rather modern, or even postmodern, approach. In fact, historian Étienne de la Vaissière has shown the accuracy of Tabari’s writing about the conquest of Sogdiana—specifically the defeat of Panjikent’s leader, Devashtich, at Mount MughThe Castle on Mount Mugh and Its Documents Learn more about Mount Mugh—by matching it with Sogdian documentary sources that only in the last century have become available to us (see below). Other Muslim sources—both historians (including Tabari) and geographers—allow us to understand the extent of Sogdian influence and actual geographic expansion.

Such Arabic, Persian, and Chinese sources, some stretching back to the glory days of the Sogdians, thus contained significant information about Sogdiana. However, with much of the data coming from secondary rather than primary sources, and being purely textual in nature, these sources were still limited in how much they could clarify about Sogdian culture. Moreover, these texts were written by outsiders to Sogdian culture. There was no means of understanding Sogdian life from the “inside,” through Sogdian writings or material culture. But that was all to change during the age of imperial expansions in the late 19th century.

Sogdian Discoveries in the Age of Empire

The key to the rediscovery of the Sogdians in the 19th century was the convergence of Western imperialism in Central Asia with the growth of archaeology as a discipline. As the Russian empire spread east and Central Asia became Russian Turkestan by the mid-19th century, Russian explorers and geographers began to note architectural remains surviving as crumbling city walls and towers. These remnants had naturally been noted by the local populace, who called them by such terms as tepe (hill) or kala or qal’a (fort), usually adding the name of an epic character such as Afrasiab (a king and hero in the epic Shahnameh) or a name based on the mound’s appearance or topography.

Excavations began in 1867 at the once-thriving 10th–11th-century trading center of Jankent (east of the Aral Sea in the valley of the lower Syr-Darya, in present-day Kazakhstan). Exaggerated reports of its “treasures” fueled archaeological interest in other sites, including those of Sogdiana. In 1875, excavation began on the mound known as Afrasiab , the name given to the ruins of ancient and early medieval Samarkand (Marakanda in the 4th century BCE, known from Alexander’s Sogdian expedition)—the chief city of Sogdiana.

As Russia gathered Central Asia into the folds of its empire, public interest in the area and its antiquities grew, with local archaeological and antiquarian societies appearing in the now-Russified Central Asian cities. The first of these, founded at Tashkent in 1894, thrived until 1916, publishing in its Transactions articles and communications about the archaeology and history of the region. Among these articles were several about the clay ossuaries discovered in the region.

Fig. 4 Ruins of an ancient watchtower near Dunhuang, in Gansu Province, Western China. It was in the ruins of a tower such as this that Sir Aurel Stein found the mail pouch containing the Sogdian Ancient Letters.

“Summer Vacation 2007, 263, Watchtower In the Morning Light, Dunhuang, Gansu Province” by The Real Bear is licensed under CC BY 2.0. https://flic.kr/p/4onCCH.

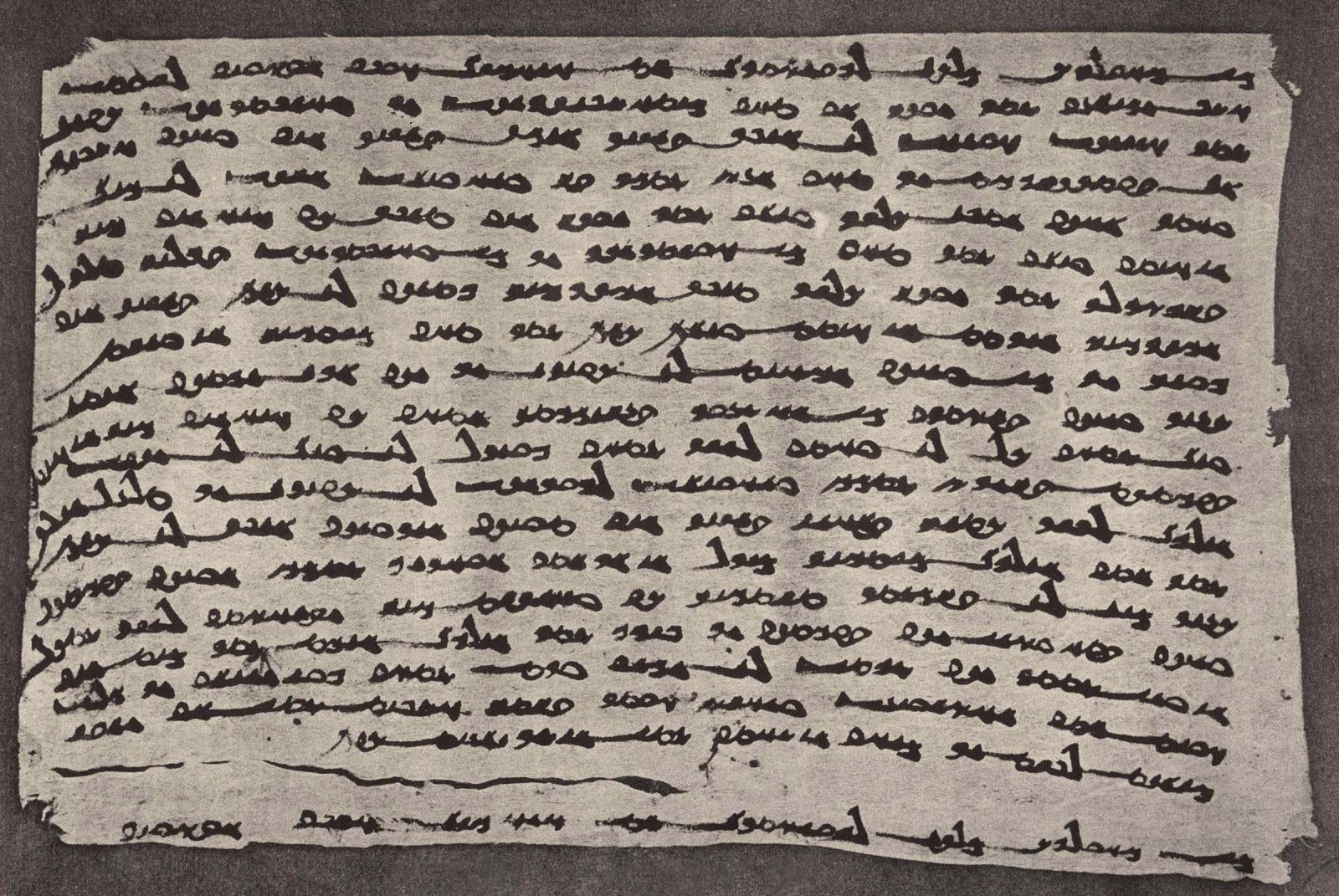

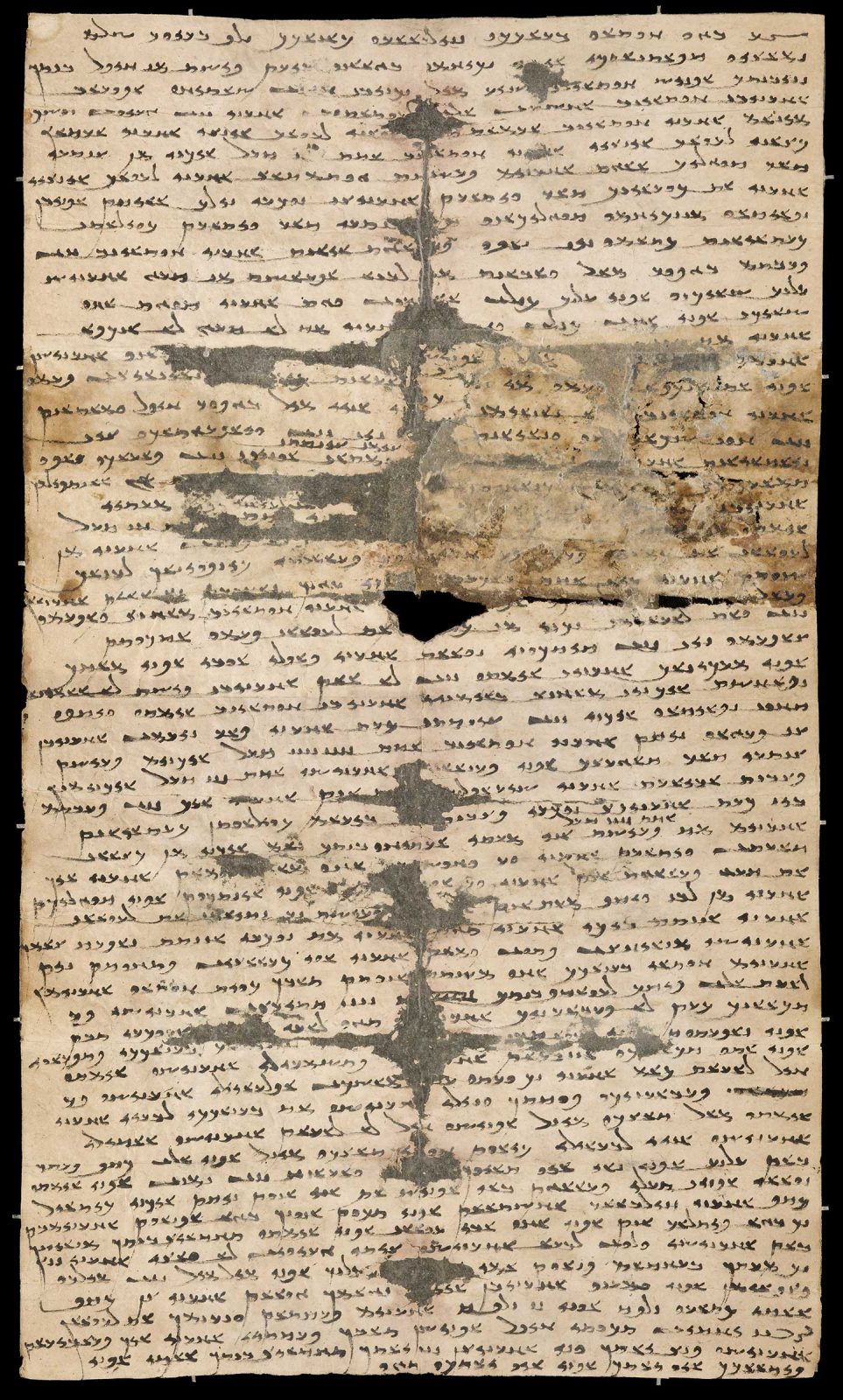

At the same time as the Russians were making extraordinary finds across its imperial territories, British and French explorers were also busy making their own discoveries, driven by the intertwined motives of imperial rivalry and thirst for knowledge. In 1907 it was the great explorer and polymath Marc Aurel Stein (1862–1943) who discovered the so-called “Ancient Letters” at Dunhuang in western China; Figs. 4–6. These not only advanced our knowledge of the Sogdian language but offered a view into the lives of Sogdians living in China in the early 4th century CE; Fig. 7.

Fig. 5 Sogdian Ancient Letter 1. 4th century CE. Discovered in 1907 at watchtower (T.XII.A), west of Dunhuang 敦煌, Gansu Province, China. Ink on paper; H. 42 × W. 24.3 cm. View object page

© The British Library Board, Or. 8212/92.

Fig. 6 Sogdian Ancient Letter 2, 312 or 313 CE. Discovered in 1907 at watchtower (T.XII.A), west of Dunhuang 敦煌, Gansu Province, China. Ink on paper; H. 42 × W. 24.3 cm. View object page

© The British Library Board, Or. 8212/95.

Fig. 7 Nicholas Sims-Williams (School of Oriental and African Studies) talks about the rediscovery of the Sogdian language.

This interest in Central Asian archaeology was not confined to European powers. The discoveries by Stein and others, and the resulting network of Western scholarship on Central Asia prompted Count Otani Kozui 大谷光瑞 (1876–1948), abbot of a Japanese Buddhist sect, to organize three archaeological expeditions between 1902 and 1914 to what was then Eastern Turkestan (today’s Xinjiang , China); Fig. 8. Not only did Count Otani hope his explorations would place Japan on par with European scholarship, he sought traces of his own Buddhist religion and to understand how Buddhism found its way to Japan. The results of these explorations in Xinjiang were, unfortunately, mixed. Financial scandal forced Otani to withdraw after the first expedition, but a highlight of his team’s discoveries was the Buddhist cave temple complex of Kizil with its astounding wall paintings. The two subsequent expeditions to Turfan, Karashahr, Kucha, and to Dunhuang (Gansu Province) yielded manuscripts as well as silk and other objects; Fig. 8.

These forays into western China and eastern Central Asia did result in manuscript finds similar in scope and variety to those acquired by Europeans. Importantly, though, the Japanese explorers’ main interest in tracing the roots of Buddhism led to their launching expeditions into many other regions where Buddhism had been established, such as India, Tibet, Thailand, Cambodia, Mongolia, and China.

Such archaeological discoveries spurred a return to textual sources about the Sogdians among scholars, now keen to link what they found in the soil to what could be found in the library. In 1926, Kuwabara Jitsuzo 桑原 隲藏 (1871–1931) collected references and other traces of Sogdians in the Chinese sources, making these valuable sources more accessible to scholars. Although Chinese scholars were not so quick to send archaeological expeditions as the Europeans and Japanese, they—like the Japanese—also showed a renewed interest in ancient textual sources on Central Asia. One important text in this regard was a work by Zhang Xinglang 張星烺, Compendium of historical documents on Sino-foreign communications, published in Chinese in the 1930s, which touched on Chinese historical references to Sogdiana and Sogdians.

Soviet Archaeology and the Discoveries in Sogdiana

As Imperial Russia turned into the postrevolutionary Soviet Union, the new Soviet regime supported archaeological exploration in its five Central Asian republics (the “-stans”). This work was conducted by Russian and Central Asian archaeologists affiliated with local universities or branches of the Soviet Academy of Sciences, or institutions such as the State Hermitage Museum, Leningrad (now St. Petersburg). Among the most significant Sogdian finds of this time were the palace at Varakhsha in the Bukhara oasis, the documents and other finds on Mount Mugh, the town of Panjikent, and the discovery of wall paintings at Afrasiab. These individual excavations are outlined below.

Varakhsha

It was in 1937, when archaeologist Vasilii A. Shishkin observed the outlines of rooms on the surface of the mound of Varakhsha, that scientific excavation of a Sogdian site began. Situated northwest of Bukhara, Varakhsha was well known to historians for the role it had played in the history of Bukhara during the Arab conquests of the early 8th century; see Fig. 9. From the later written sources—in particular, the History of Bukhara by Muhammad Narshakhi (943–44 CE)—we know of its importance in the annual religious and agricultural festival presided over by the ruler of Bukhara, the Bukhar Khuda. The history tells, too, of Varakhsha’s becoming the residence of the Bukhar Khuda when he moved the royal court there from Bukhara; that it was also a major crafts production center; and that, thanks to an extensive irrigation system of canals, it encompassed a vast agricultural area. One of the rooms that Shishkin first excavated was filled with ornamental and figurative stuccos; Figs. 10 and 11.

Fig. 10 Figural and Ornamental Stuccos. Large iwan [hall], Palace at Varakhsha, Uzbekistan (in ancient Sogdiana), late 7th–early 8th century CE. Stucco; H. 23 × W. 57 cm (mouflon ram). State Museum of History, Moscow.

After V. A. Shishkin, Varakhsha (Moscow: USSR Academy of Science Publishing, 1963), 168 (fig. 77) and 182 (fig. 99). Photograph © The State Hermitage Museum.

Fig. 11 Figural and Ornamental Stuccos. Large iwan [hall], Palace at Varakhsha, Uzbekistan (in ancient Sogdiana), late 7th–early 8th century CE. Stucco; H. 23 × W. 57 cm (mouflon ram). State Museum of History, Moscow.

After V. A. Shishkin, Varakhsha (Moscow: USSR Academy of Science Publishing, 1963), 168 (fig. 77) and 182 (fig. 99). Photograph © The State Hermitage Museum.

Another room—which became known as the Red Hall—contained extraordinary paintings; Fig. 12. Excavations halted during World War II, but afterward resumed and continued until 1954. During this time, due to the exactitude of its excavation, recording system, and preservation, Varakhsha became (as Panjikent still is) a training ground for future archaeologists, conservators, restorers, architects, and others interested in premodern Central Asia.

Subsequent expeditions to the site have not greatly advanced our knowledge of the palace building, except to determine three different stages for one part of the structure. Even so, Narshakhi’s discussion of the palace has allowed archaeologist/numismatist Aleksandr Naymark (with the help of other Islamic period sources, careful study of coins associated with the rulers of Bukhara, and art historical analysis) to suggest five datable building phases for the palace. These range from the last quarter of the 7th century into the third quarter of the 8th.

Mount Mugh

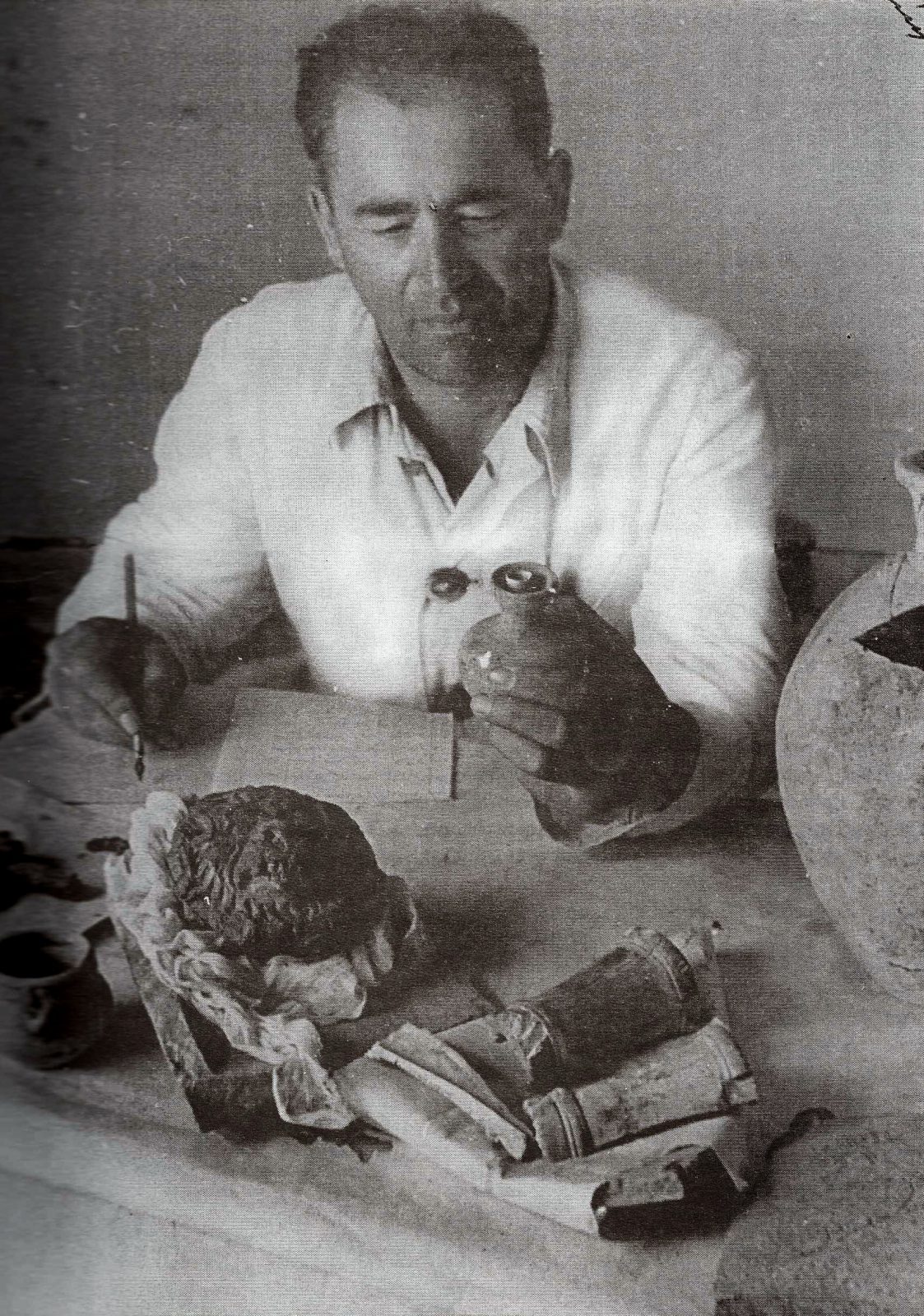

In a remote mountain area, 150 meters (492 feet) above the confluence of two rivers, the Zerafshan and the Qom, stands the fortress of Mount Mugh, a site both famous and infamous for the history of Sogdiana and our knowledge of that history; Figs. 14–15. There, in 1932, a shepherd from a nearby village found a scrap of manuscript with writing on it in an alphabet that, at the time, only a few scholars could read; Fig. 16.

Miraculously, the scrap found its way to Leningrad (now St. Petersburg), where Aleksandr A. Freiman (1879–1968), a specialist in Iranian studies, recognized the script as Sogdian. Because of the discoveries made decades earlier at Dunhuang and other sites in western China and present-day Xinjiang, the Sogdian language was becoming better understood. Yet this was the first piece of Sogdian writingSogdian Language and Its Scripts Learn more about the Sogdian language ever found in Sogdian territory. The next year saw the dispatch of an expedition from Leningrad to Mount Mugh, where excavation revealed over 400 items relating to Sogdian material culture, 6 coins, and 81 documents written on Chinese paper, parchment, and wooden sticks. In addition to 74 documents in the Sogdian language, excavators found one written in Arabic, one in Turkish runic script, and several in Chinese—a miscellany of records (including a marriage contract) that fleeing Panjikenters had brought with them to Mount Mugh.

What the Mount Mugh expedition had discovered was the archive of the “lord of Panj” and self-proclaimed “king of Sogd, lord of Samarkand”—Devashtich (r. 708?–722), the last ruler of Panjikent, some 60 km (37 miles) to the west. With the Turkic wresting of Sogdian territory from the Hephthalites (another Central Asian group), it seems that most if not all rulers of Sogdian cities were Turks. Although it is uncertain whether Devastich himself was Turkic or Sogdian, he seems to have shared power with Panjikent’s nobles. The latest document recovered at Mugh states that Devashtich had ruled in Panjikent for fourteen years and was in his second year of rule at Samarkand. These and related events have been reconstructed from Devashtich’s surviving letters but they remain murky. It appears, however, that despite having professed fealty to the Arabs (and possibly converting to Islam), Devashtich declared himself the legitimate ruler of Sogdian Samarkand—and essentially, all of Sogdiana. Fleeing Panjikent with his loyalists, Devashtich clashed with the Arab army and sought refuge in his citadel atop Mount Mugh. Outnumbered, he and his followers surrendered, Although promised safe passage into captivity, Devashtich was eventually crucified and beheaded.

Panjikent

Although the site of Panjikent had been known since 1870, the Mount Mugh discoveries of the 1930s prompted Russian archaeologists to excavate there. Situated about 60 km (ca. 37 miles) from both Samarkand and Mount Mugh, and thus equidistant between them, Panjikent is the easternmost city of ancient Sogdiana. Limited explorations were conducted from 1937 to 1940. Yet it was not until 1947 that a team of archaeologists, architects, historians, art historians, philologists, and numismatists assembled by Aleksandr Yakubovsky (1886–1953) brought the remains of 6th- to mid-8th century Sogdian Panjikent so fully to light (and to life, earning the town the nickname “the Sogdian Pompeii”). Meticulous excavation, recording, analysis, and conservation have produced the extraordinary results visible in this digital exhibition. After Yakubovsky’s death, Aleksandr A. Belenitsky (1904–1993), a member of the original team, took over its direction and made significant excavations, including the famous Rustam Cycle wall paintings Fig. 18-20.

Fig. 18 Rustam Cycle (installation view of north and east walls). Panjikent, Tajikistan (in ancient Sogdiana), Site VI:41, ca. 740 CE. Wall painting. The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, SA-15901-15904. View object page

Photograph © The State Hermitage Museum.

Fig. 20 Archival footage from Aleksandr M. Belenitsky’s excavations of the Rustam Cycle.

Courtesy of the archive of Galina Aleksandrovna Belenitskaya

Over the decades, Panjikent has been a training ground for archaeologists; Fig. 22. These have included Boris I. Marshak (1933–2006) Boris Marshak Learn more about the Russian scholar Boris Marshak and his wife and frequent coauthor, Valentina I. Raspopova; philologists, especially the late Vladimir A. Livshits (1923–2017), who produced definitive translations of the Mount Mugh Sogdian documents; the historian of ancient Iranian history and culture Vladimir G. Lukonin (1932–1984); and conservators from the State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg, which has been the organizing institution since the early days of the excavations. In 1978, with Belenitsky’s retirement, Marshak assumed directorship, developing new excavating techniques and contributing to the expertise of younger archaeologists. With Marshak’s untimely death, Pavel B. Lurje took on leadership along with Tajik archaeologist Sharofuddin Kurbanov.

Boris Marshak Learn more about the Russian scholar Boris Marshak and his wife and frequent coauthor, Valentina I. Raspopova; philologists, especially the late Vladimir A. Livshits (1923–2017), who produced definitive translations of the Mount Mugh Sogdian documents; the historian of ancient Iranian history and culture Vladimir G. Lukonin (1932–1984); and conservators from the State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg, which has been the organizing institution since the early days of the excavations. In 1978, with Belenitsky’s retirement, Marshak assumed directorship, developing new excavating techniques and contributing to the expertise of younger archaeologists. With Marshak’s untimely death, Pavel B. Lurje took on leadership along with Tajik archaeologist Sharofuddin Kurbanov.

As a wealthy mercantile town within the oasis of Samarkand, Panjikent commands a perhaps disproportionate yet well-deserved place as the quintessential Sogdian city. This is in large part because of the range and quality of the finds there, and the careful way in which they have been excavated, recorded, and conserved. Without deflecting awe and appreciation of the art and lifestyle of the ancient Panjikenters, we eagerly anticipate the results from other excavations, such as at Paikend , in the Bukhara oasis.

Afrasiab

At the beginning of the 20th century, fragments of wall paintings had been discovered in Afrasiab, but it was only in 1965, when bulldozers ran through the middle of the site to build a roadway, that the remains of Afrasiab’s magnificent wall paintings were fully revealed. Although destruction of the upper portion of the walls had already occurred in the 10th and 11th centuries, this modern shaving of the surface afforded archaeologists access to a series of rooms that had been adorned with paintings during the middle of the 7th century. Now known as the Hall of the Ambassadors, the walls of this relatively small square room are covered with a figural cycle depicting Sogdiana and its neighbors with references to specific festivals—all, unfortunately, in fragmentary condition; Fig. 22. Despite lengthy interruptions, excavations continue to the present, now under the direction of an Uzbek-French archaeological team.

Fig. 22 Click to enlarge and scroll through the South wall of the “Hall of the Ambassadors.” Afrasiab (present-day Samarkand), Uzbekistan (in ancient Sogdiana), Site XXIII:1, mid-7th century CE. Wall painting; H. 3.4 × W. 11.52 m. Afrasiab Museum. View object page

Photograph by Thorsten Greve © Association pour la sauvegarde de la peinture d’Afrasiab, and Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

The Last Fifty Years: Uncovering the Sogdians Farther Afield

Alongside the archaeological discoveries of the Sogdians at home in Sogdiana, the last fifty years have seen a transformation in our understanding of the Sogdians abroad, too. For evidence of them in South Asia, Nicholas Sims-Williams has deciphered many Sogdian (and other) inscriptions on the rocks of the Upper Indus River Valley . Carved by merchants and pilgrims on their journeys to and from eastern Central Asia and China, these words and occasional drawings show the extent of overland travel associated with Sogdian mercantile activity (and, to a lesser extent, with Buddhist pilgrimages).

More recently, another group of documents has shed light on the region during the last century of the Achaemenid rule. Numbering thirty in all, they are written on leather in Aramaic, the lingua franca of the time, and were composed in the 4th-century BCE court of the Achaemenid satrap, who governed land that extended into Sogdiana, although he resided in Bactria . Thus, these “ancient Aramaic documents” have confirmed for scholars that Sogdiana did not have its own satrap, or governor. Even though Cyrus the Great had conquered Sogdiana around 540 BCE and established the town of Kyreschata (Cyropolis)—modern Kurkath on the river Jaxartes (Syr Darya) as the farthest northeastern reach of his empire, Sogdiana apparently never became a full-blown Achaemenid satrapy. Governed from Bactria, Sogdiana was considered a distant frontier province—similar perhaps to the way the British crown in the late 18th century viewed its Australian colony. More significantly, the Bactrian Aramaic documents reflect Achaemenid administrative practices in Bactria and Sogdiana and provide valuable place names. In short, these scraps of leather opened a previously unknown window onto the lives of soldiers, farmers, and others living under Persian rule.

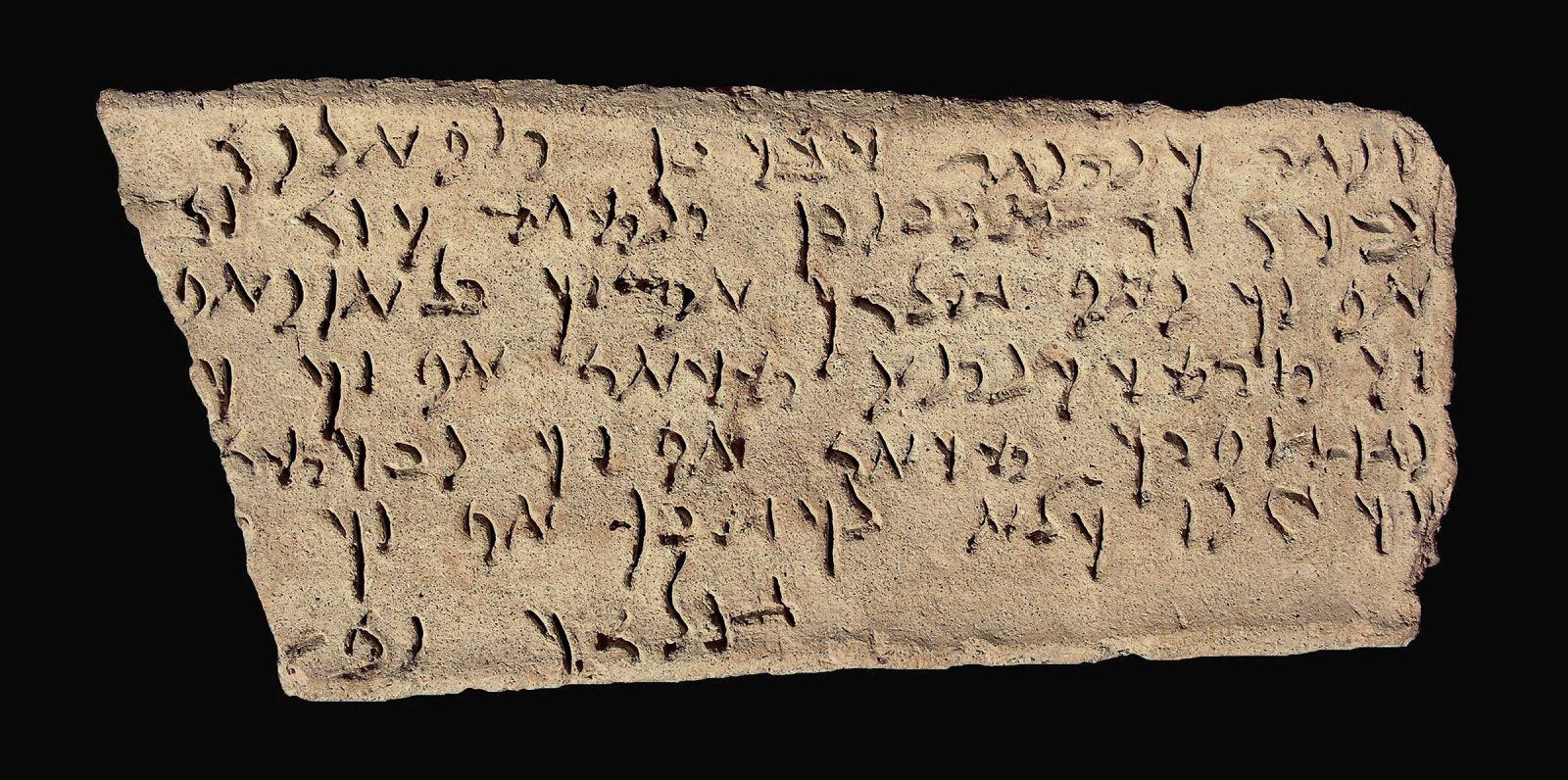

The most recent textual find—one that confirms the Hou Han Shu’s report about Sogdians well to the north of Sogdiana proper—are several fragmentary baked-clay plaques from Kultobe in southern Kazakhstan; Fig. 23. These may date to as early as the 1st or 2nd century CE. In an archaic Sogdian script, these plaques record the colonization of the region by Sogdians from Samarkand, Bukhara, and other cities, and the division of the land between them and the nomadic people already living there.

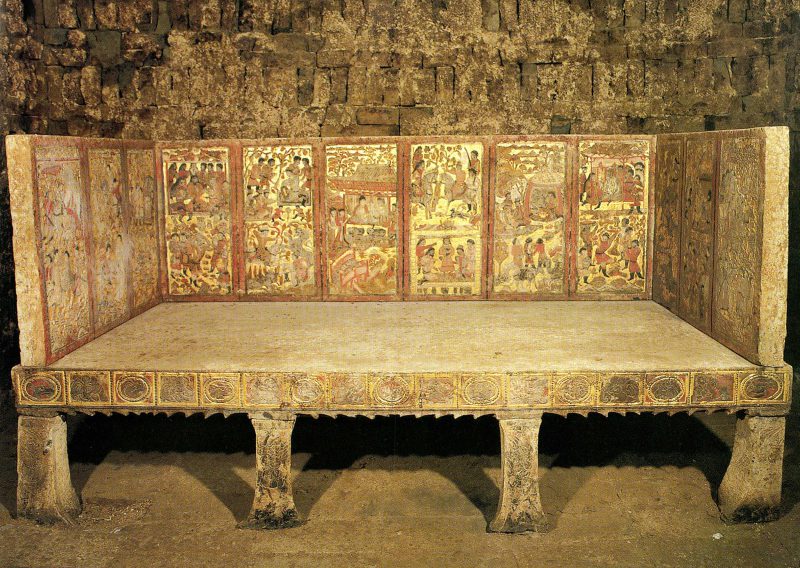

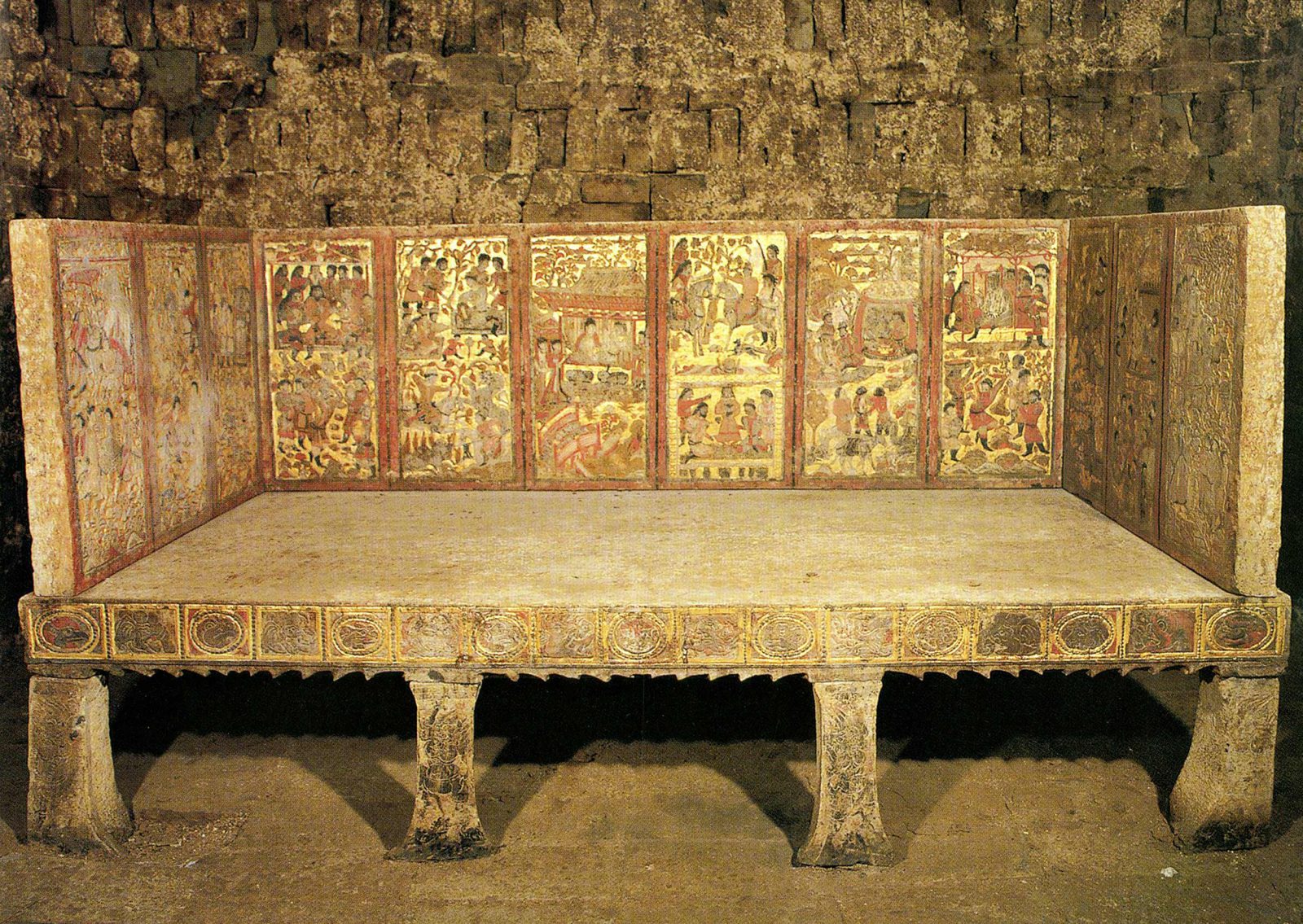

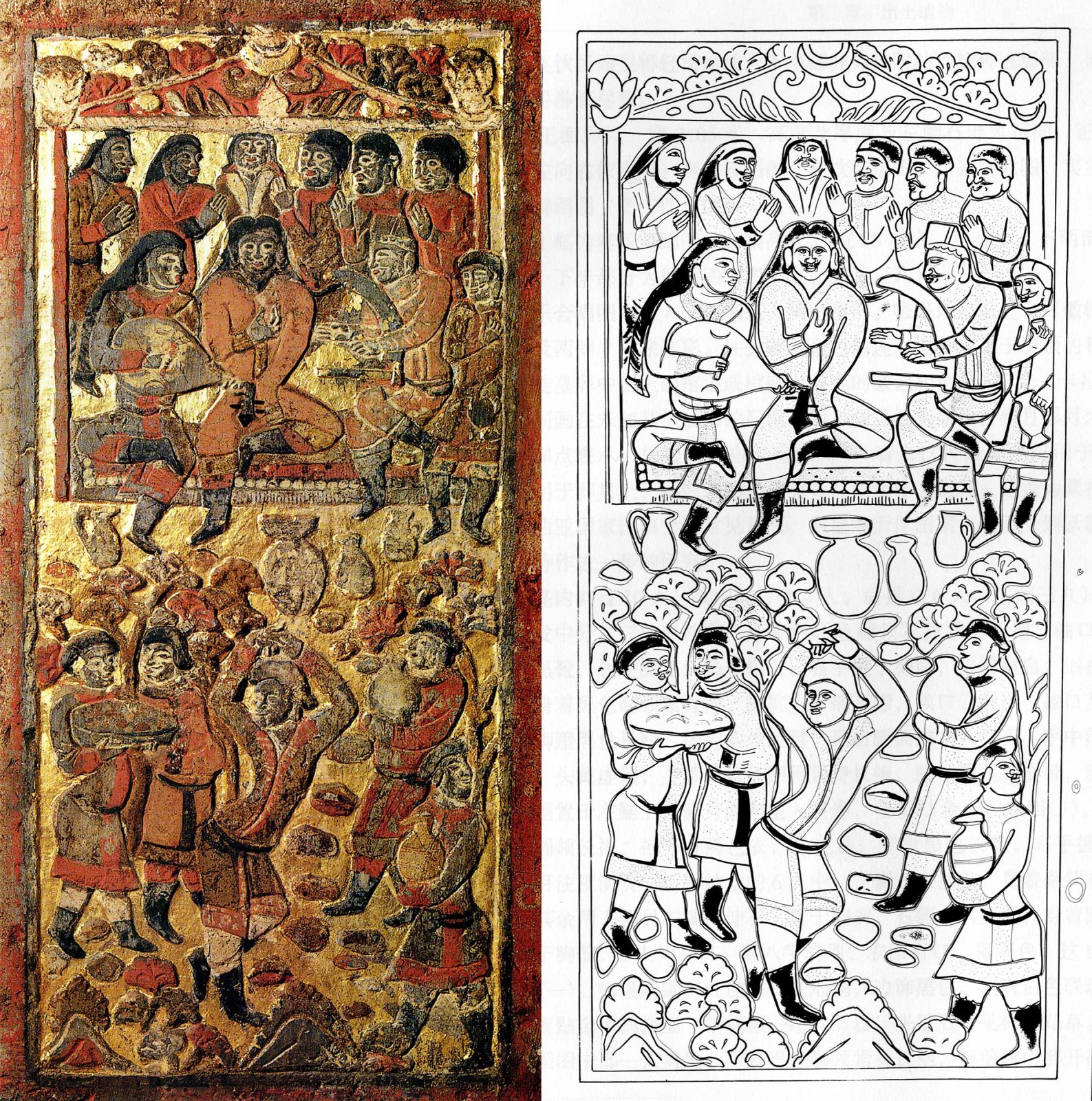

It was Giustina Scaglia who first recognized in the 1950s that such funerary furniture was made for privileged Sogdians residents in China. It was she who realized the connections among parts of a funerary bed that had been divided among several museums (side and back panels, a screen or possibly gate posts at the front, and a base); Figs. 27–30. The bed would be confirmed to be the resting place of a deceased Central Asian, specifically one who came from Sogdiana in the 6th century, at a time when the area was dominated by the Hephthalites. Since the beginning of the 1980s, a number of beds and sarcophagi from the 6th and early 7th centuries have come to light—some excavated, others by way of the art market. Most of the information we have from them is from their epitaphs, which show they belonged to Sogdians whose families had emigrated to China generations earlier.

Today, a truly international community of scholars is working separately and collaboratively on multiple research projects connected to Sogdiana. Archaeologist and historian Sören Stark, who teaches at the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World (New York University), is carrying out pioneering archaeological work in Central Asia in order to understand the life of Sogdian “non-elites” and rural life, a subject that has often been overlooked by scholars more interested in the more visually attractive and bountiful material culture of the urban elites of Sogdian society.

Fig. 31 Sören Stark (Institute for the Study of the Ancient World, New York University) discusses his research into the rural society of Sogdiana.

Fig. 32 Piece of sandalwood with Sogdian inscription.

After Tono Haruyuki, “Inscriptions on the Scented Woods in the Hōryuji Treasures and Ancient Incense Trade,” Museum: Art Magazine Edited by the Tokyo National Museum, No. 433 (April 1987): 10.

Fig. 33 Bilingual epitaph from the tomb of Shi Jun (Wirkak) and Wiyusi. China, Xi’an 西安市, Shaanxi Province 陝西省. Northern Zhou dynasty (557–581 CE); dated to 579–80 CE. Stone carvings with traces of pigment and gilding. Shaanxi History Museum, Xi’an, China. View object page

Image courtesy of Shaanxi Provincial Institute of Archaeology.

In Japan, interest in Sogdian culture, as well as in Sogdian and other Middle Iranian texts, remains strong, with one of its leading scholars being Yutaka Yoshida of Kyoto University. Among his other contributions, it was he who read Wirkak/Shi Jun’s Sogdian epitaph and published the pieces of sandalwood preserved in the Shoso-in Repository of the Todai-ji Temple, in Nara, Japan ; Fig. 32. In China, Rong Xinjiang 榮新江 has researched and written extensively on Sogdians in Xinjiang and in China proper, focusing on their mercantile activities, their relationship to the Chinese administration—in particular the office of sabao 薩保—and their Mazdean religious practices. The position of sabao has aroused debate among Chinese scholars. Rong and Jiang Boqin 姜伯勤 view the sabao as a leader of his local Central Asian and Iranian community for matters both political and religious, for the settlement and governance of foreign peoples in their respective communities, and for maintaining ritual activity. In contrast, Luo Feng 羅丰 argues that the sabao also played a role in the commercial transactions of these communities, especially in foreign trade. On the inscribed epitaph stones discovered in Shi Jun’s and An Qie’s tombs, Fig. 33, and on the decorated sarcophagus and bed in their respective tombs, the owner’s administrative and possibly diplomatic status is stressed. Shi Jun, however, is also depicted as part of a caravan, perhaps referring to his trading activities, whereas An Qie’s epitaph mentions an additional function, achieved later in life (and possibly honorific), as a military governor. In addition to illustrating these offices conferred by the Chinese government, both men represent themselves participating in the “good life” Banqueting in Sogdiana Learn more about banqueting in Sogdiana of a Sogdian aristocrat, feasting and hunting; Figs. 34 and 35.

New digital technologies are also allowing for increased collaboration and new research. Kansai University in Japan, for example, has created a digital 3-D model of the Anyang funerary bed, whose various parts had been divided and scattered across institutions across the world and had been brought together in print by Scaglia, as mentioned above; Fig. 36.

Three-dimensional scanning and photogrammetry technologies are making objects accessible to the public and scholars alike in a way never seen before. This digital exhibition is playing its own part in this endeavor, acting as a catalyst for the production and dissemination of high-resolution photography and 3-D scans of various objects connected to Sogdian culture, such as the cup and ewer below Figs. 37 and 38. The project has also involved the more old-fashioned approach of convening workshops and meetings in the United States and China for scholars of Sogdian art and culture from around the world.

Conclusion

This brief overview of the “rediscovery” of the Sogdians over the last 120 years has illustrated the various means by which scholars have been able to bring back a culture once thought in the West to be lost to time. First, the essay has illustrated how a surprising amount of information was preserved in texts in a variety of languages—Greek, Persian, Arabic, and Chinese. This has meant that a certain amount of valuable data has been gained from the collation of scattered references to the Sogdians found in multiple texts around the world. Second, we have seen how the “age of empire” of the late 19th and early 20th century led to a range of crucial discoveries of Sogdian material culture by British, Russian, French, German, and Japanese scholars. Such material culture has allowed the Sogdians to “speak,” as it were, for the first time since the disappearance of a coherent Sogdian political and cultural entity by the 9th century CE. Since the early 20th century, further archaeological discoveries, primarily by Soviet scholars but increasingly by an international community of researchers from across Europe and Asia, have deepened our understanding of various dimensions of Sogdian culture. These range from Sogdians’ views of the afterlife to the ways they dressed for dinner. It is an exciting thought to imagine what the next 100 years of research may uncover.

https://depts.washington.edu/silkroad/texts/hhshu/hou_han_shu.html#sec17 and https://depts.washington.edu/silkroad/texts/hhshu/notes17.html#1

John E. Hill, Through the Jade Gate to Rome: A Study of the Silk Routes during the Later Han Dynasty 1st to 2nd Centuries CE; An Annotated Translation of the Chronicle on the ‘Western Regions’ from the Hou Hanshu, 2-vol. revised and expanded 2nd ed., bilingual English/Chinese (www.booksurge.com 2009), 33 and 371.

Samuel Beal, trans., Si-Yu-Ki: Buddhist Records of the Western World Translated from the Chinese of Hiuen Tsiang (A.D. 629) (London: K. Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co., 1906).

For an accessible translation, see Ehsan Yarshater, ed., The History of al-Tabarī (Albany: State University of New York Press; New York: Bibliotheca Persia, 1987–97).

Étienne de la Vaissière, “Historiens arabes et manuscrits d’Asie centrale: quelques recoupements,” Revue des mondes musulmans et de la Méditerranée: Écriture de l’histoire et processus de canonisation dans le monde musulman des premiers siècles de l’islam, hommage à A.-L. de Prémare 129 (2011): 119–123.

Richard N. Frye, “Sughd and the Sogdians: A Comparison of Archaeological Discoveries with Arabic Sources,” Journal of the American Oriental Society 63, no. 1 (1943): 14–16.

Aleksandr Belenitsky [Belenizki], Archaeologia Mundi: Central Asia. Trans. James Hogarth (Cleveland and New York: The World Publishing Company, 1968), 18. For an overview, see also Boris A. Litvinskij, “Archaeology in Tadžikistan under Soviet Rule,” East and West 18, nos. 1–2 (1968): 125–46; and Grégoire Frumkin, Archaeology in Soviet Central Asia: Handbuch der Orientalistik, III: Innerasien (Leiden and Cologne: E. J. Brill, 1970).

John Timothy Wixted, “Some Sidelights on Japanese Sinologists of the Early Twentieth Century,” Sino-Japanese Studies 11, no. 1 (1998): 68–74.

See Zhang Xinglang 張星烺, Zhong xi jiaotong shiliao huibian 中西交通史料匯編 [Compendium of historical documents on Sino-foreign communications] (Beijing: Furen University Library, 1930). See also Rong Xinjiang 荣新江, “Research on Zoroastrianism in China 1923–2000,” China Archaeology and Art Digest 4, no. 1 (2000): 7–14; as well as the 1930 publication by historian Xiang Da 向达, Chang’an [Xi’an] and the Civilization of the Western Regions in the Tang Period, cited by Rong Xinjiang, “New Light on Sogdian Colonies along the Silk Road: Recent Archaeological Finds in Northern China [Lecture at the BBAW on 20th September 2001],” Berlin-Brandenburgischen Akademie der Wissenschaften Berichte und Abhandlungen 10 (2006): 147–60.

Richard N. Frye, The History of Bukhara: Translated from the Persian Abridgement of the Arabic Original by Narshakhi (Princeton: Markus Weiner Publishers, 2007).

Aleksandr Naymark [Naimark], “Returning to Varakhsha,” The Silk Road 1, no. 2 (2003): 18–39. Available online:

http://www.silkroadfoundation.org/newsletter/december/varakhsha.htm

Among the artifacts were a painted wooden shield, as well as objects and accoutrements of daily life made of wood (eating utensils, storage chests, combs), leather (shoes, bags), and textiles of cotton, wool, and silk (including carpet fragments and hairnets).

Regarding the marriage contract, see Ilya Yakubovich, “Marriage Sogdian Style,” in Heiner Eichner, Bert G. Fragner, Velizar Sadovski, and Rüdiger Schmitt, Iranistik in Europa—Gestern, Heute, Morgen (Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 2006), 307–44. On the documents generally, see Vladimir A. Livshits, Sogdian Epigraphy of Central Asia and Semirech’e, trans. Tom Stableford, ed. Nicholas Sims-Williams. Corpus Inscriptionum Iranicarum, Part II, Inscriptions of the Seleucid and Parthian Periods and of Eastern Iran and Central Asia (London: School of Oriental and African Studies [SOAS], 2015), with a list of his previous publications of the documents.

Frantz Grenet and Étienne de la Vaissière, “The Last Days of Panjikent,” Silk Road Art and Archaeology 8 (2002): 155–96.

This places it at the border of Ustrushana, a large region closely linked to Sogdiana, bordering it on the west and southwest, and sharing with it much of its lifestyle, language, religion, and culture. Ustrushana’s major city or capital was at Bunjikat, twenty kilometers to the south of modern Shahristan. Wall paintings in a style different from those of Panjikent adorned the walls of some of its buildings, but they are fewer and less complete. See N. N. Negamatov, “Ustrushana, Ferghana, Chach and Ilak,” in History of Civilizations of Central Asia III: The Crossroads of Civilizations, ed. B. A. Litvinsky, Zhang Guangda, and R. Shabani Samghabadi, III: The Crossroads of Civilizations, A.D. 250 to 750 (Paris: UNESCO Publishing, 1996): 259–77.

Vladimir A. Livshits, Sogdian Epigraphy of Central Asia and Semirech’e, trans. Tom Stableford, ed. Nicholas Sims-Williams. Corpus Inscriptionum Iranicarum, Part II: Inscriptions of the Seleucid and Parthian Periods and of Eastern Iran and Central Asia (London: School of Oriental and African Studies [SOAS], 2015), with a list of his previous publications of the documents.

Nicholas Sims-Williams, Sogdian and Other Iranian Inscriptions of the Upper Indus I. Corpus Inscriptionum Iranicarum, Part II: Inscriptions of the Seleucid and Parthian Periods and of Eastern Iran and Central Asia, III: Sogdian (London: School of Oriental African and Asian Studies [SOAS], 1989 and 1992). Also Nicholas Sims-Williams, “The Sogdian Merchants in China and India,” in Cina e Iran da Alessandro Magno alla dinastia Tang, vol. 5, ed. Alfredo Cadonna and Lionello Lanciotti (Florence: Leo S. Olschki Editore, 1996), 45–67.

Joseph Naveh and Shaul Shaked, The Khalili Collection: Ancient Aramaic Documents from Bactria (Fourth Century B.C.E.). Corpus Inscriptionum Iranicarum, Part 1: Inscriptions of Ancient Iran. Volume V: The Aramaic Versions of the Achaemenid Inscriptions, etc. Texts II (London: The Khalili Family Trust, 2012). Also included are eighteen inscribed wooden sticks used as tallies, recording amounts of provisions to certain persons from the satrap’s storehouse. Most are dated to the third year of the last Achaemenid monarch, Darius III (c. 377 BCE), and one is in the seventh year of Alexander (349 BCE).

Nicholas Sims-Williams and Frantz Grenet, “The Sogdian Inscriptions of Kultobe,” Shygys, no. 1 (2006): 95–111; Nicholas Sims-Williams, Frantz Grenet, and Aleksandr Podushkin, “Les plus ancient monuments de la langue sogdienne: Les inscriptions de Kultobe au Kazakhstan,” in CRAI (Comptes rendus des séances de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres) 151 (2007 [2009]): 1005–34. For a different view, see Étienne de la Vaissière, “Iranian in Wusun? A Tentative Reinterpretation of the Kultobe Inscriptions,” in Sergei Tokhtasev and Pavel B. Luria, ed., Commentationes Iranicae: Vladimiro f. Aaron Livschits nonagenario donum natalicium (St. Petersburg: Nestor-Historia, 2013), 320–25.

Giustina Scaglia, “Central Asians on a Northern Ch’i Gate Shrine,” Artibus Asiae 21 (1958): 2–18.

For the inscription, see Yutaka Yoshida, “The Sogdian Version of the New Xi’an Inscription,” in Étienne de la Vaissière and Éric Trombert, eds., Les Sogdiens en Chine (Paris: École français d’Extréme-Orient, 2005), 57–72. See also Yutaka Yoshida, “In Search of Traces of Sogdians: ‘Phoenicians of the Silk Road’ (Lecture at the BBAW on the 5th of October 1999),” Berlin-Brandenburgische Akademie der Wissenschaften. Berichte und Abhandlungen 9 (2002), 186–200.

Rong Xinjiang, “Sogdian Merchants and Sogdian Culture on the Silk Road,” in Empires and Exchanges in Eurasian Late Antiquity: Rome, China, Iran, and the Steppe, ca. 250–750, ed. Nicola Di Cosmo and Michael Maas (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018): 84–95.