Sogdian Metalworking

by Judith A. Lerner

Metalworking in gold, silver, and bronze was one of the crafts in which Sogdian artisans particularly excelled. Many Sogdian metalwork shapes and techniques influenced Chinese metalwork and continued, with modifications over time, in Muslim Central Asia and Iran. The value of the Sogdian workmanship was such that their metalcrafts were traded extensively. Sogdian vessels—mainly silver—have been found in diverse regions of Asia, from points along the east–west Silk and northern Fur Routes in northern and southern Russia to areas of Central Asia beyond Sogdiana, and in China; Fig. 1.

Although often found with Sasanian silver vessels, no Sogdian vessels have yet been excavated in Iran, and with one exception, no Sogdian inscription has been found on Sasanian silver to indicate Sogdian ownership. What accounts for this? Most likely, it was the Sasanians’ “blockade” of Sogdian trade, especially silk, from their territory. True to the Chinese saying that “men of Sogdiana go wherever profit is to be found,” Sogdian merchants persuaded their new Turkic overlords to send a delegation to Constantinople via a northern route (avoiding Sasanian territory) to establish a market for Sogdian silk in Byzantium; Fig. 2.

At first glance, Sogdian metalwork resembles that of the Sasanians (and, indeed, some scholars still confuse the two), but differences, subtle and otherwise, differentiate them by shape, technique, and iconography. Boris I. Marshak, the Russian archaeologist most identified with the Sogdian town of Panjikent , as well as an expert on Sogdian metalwork, has demonstrated several characteristics of Sogdian vessels; Fig. 3.

Fig. 3 Pavel Lurje (The State Hermitage Museum) presents Sogdian metalwork on display at the State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg.

Marshak determined that Sogdian vessels tend to be less massive than the Sasanian works, with different shapes, made using different techniques, and showing a greater dynamism in their designs. The static figures of ruling kings popular in Sasanian metalwork appear in Sogdian pieces only at the end of the 8th century, when Sogdiana finally came under Muslim rule. Instead, Sogdian artisans preferred medallions, each enclosing a single animal Figs. 4 and 5.

Fig. 4 Cup with Goats. Ancient region of Sogdiana, 8th century CE. Gilded silver; H. 7.3 cm × W. 12 cm. The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, S-251. View object page

Photograph © The State Hermitage Museum.

Fig. 6 Silver and Gilt Plate Showing the Siege of a Castle Sogdian, 9th–10th century Cast, engraved, and gilded silver; Diam. 23.7 cm Found in 1909 near village of Anikova, Perm Province , Russia The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, S-46 View object page

Photograph © The State Hermitage Museum

Because so little has been scientifically excavated, it is difficult to date Sogdian metalwork, but what survives comes mostly from the last centuries of the Sogdian city-states, the late 7th and 8th centuries. A few examples of metalwork, however, are later copies, thus providing evidence of the styles and subject matter of some Sogdian metalwork that is otherwise lost; Fig. 6.

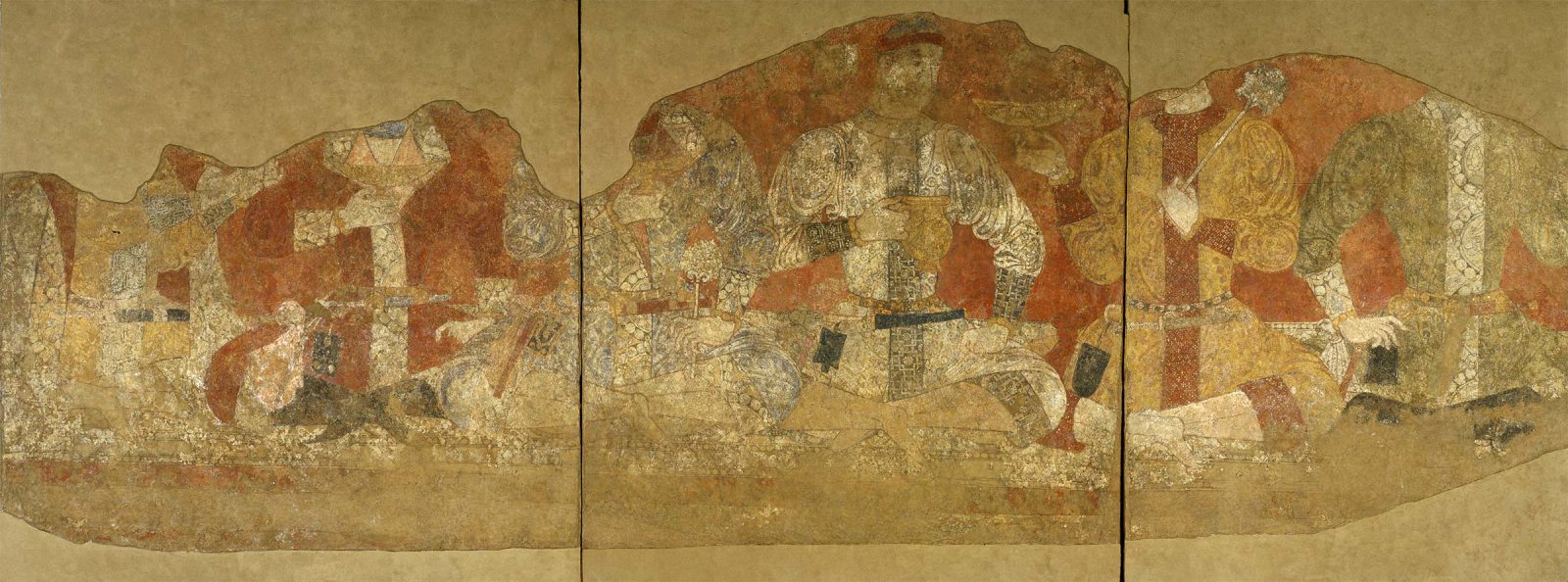

Furthermore, even though they are not actual vessels, we do get a sense of the sundry kinds of vessels and their decoration from the banqueting scenes painted at Panjikent Fig. 7 and 8. Among the varied containers for foods and liquids, we see a horn-shaped wine vessel, or rhyton, terminating in an animal head a tankardlike cup engraved with a female figure; and several shallow bowls with ring bases, also made for imbibing.

In addition to silver, Sogdian craftsmen fashioned vessels in gold, although only a single example survives Fig. 9. Its exact find spot is unknown, but it dates to the late 7th or early 8th century. Its handle is joined to its neck by the foreparts of a winged and horned dragon, a creature that has roots in ancient Eastern Iranian art and appears in metalwork of the early Islamic period. Similarly, the magnificent ewer emblazoned with a winged camel Figs. 10 and 11 shows the same type of handle attachment—an influence from Late Antique/Byzantine metalwork examples.

Fig. 10 Winged Camel Ewer. Ancient Sogdiana, late 7th–early 8th century CE. Gilded silver; H. 39.7 cm. The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, S-11. View object page

Photograph © The State Hermitage Museum.

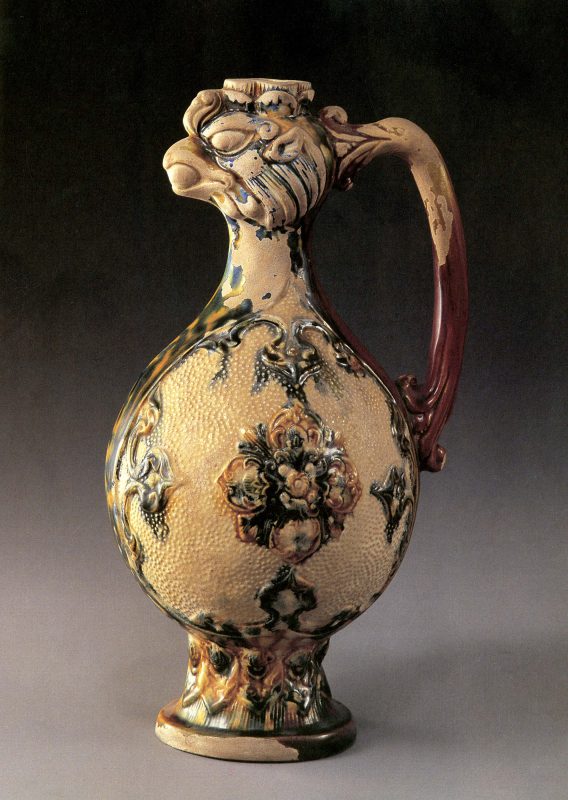

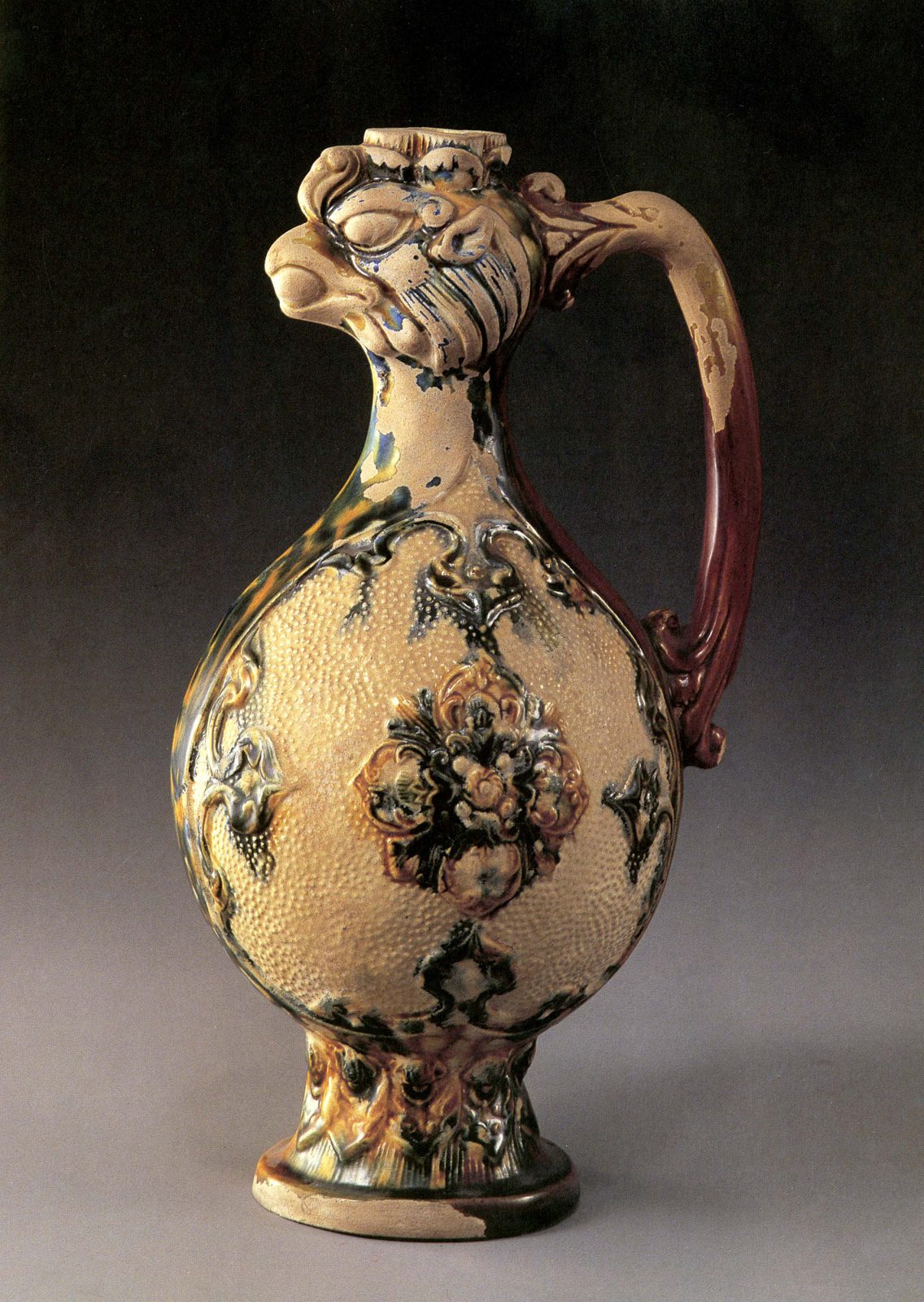

Sogdian metalwork greatly influenced that of Tang China, through imports as well as through Sogdian craftsmen working in China. We see this in the flat ring-matted background of Tang-period metalwork, which was reproduced on Tang-period ceramic ewers Fig. 13, themselves inspired by the shape of the Sogdian ewer. In like manner, the shape of the Freer Gallery cup is repeated by Tang silversmiths Fig. 14, although ultimately the shape is Greco-Roman. In fact, this cup, collected early in the last century, reportedly came from Luoyang 洛陽 (in Henan Province). Other vessels, including one akin to the fluted lion bowl in the Freer Gallery Fig. 15, were found near Xi’an 西安, and a wine service from a mid-6th-century tomb in Hebei Province contained a Chinese-made silver bowl inspired by Sogdian metalwork.

Fig. 12 Phoenix-Headed Ewer. Tang dynasty (618–906 CE), from a Tang tomb. Polychrome lead glazes over buff earthenware with molded relief decoration. H: 31 cm. Gansu Provincial Museum, Lanzhou 兰州.

After Annette L. Juliano and Judith A. Lerner, Monks and Merchants: Silk Road Treasures from Northwest China (New York: Harry N. Abrams and Asia Society Museum, 2001), 316, no. 111.

Fig. 13 Chinese wine cup of the Tang period (late 7th century CE) and a Sogdian cup (7th century CE). The Chinese example (F1930.51) follows the general outline of its Sogdian prototype (F2012.1) but is more compact and has a simpler ring. Its body, however, is more elaborate. Instead of the abstract S-shapes of the Sogdian vessel, the Chinese one is covered with chased and ring-punched designs of wildlife cavorting among grapes and foliage. View object page

Freer Gallery of Art, F1930.51 (left) and F2012.1 (right).

Fig. 14 Lobed Bowl with Lion, Foliage Enclosed in a Medallion. Possibly Uzbekistan (in ancient Sogdiana), late 6th–early 7th century CE. Silver; H. 4.8 × Diam. 15.3 cm. View object page

Purchase, Charles Lang Freer Endowment, Freer Gallery of Art, F1997.13.

Fig. 15 Click and drag the cups above and below from Fig. 13 to rotate and explore the influence of Sogdian metalwork during the early Tang dynasty. The cup on the top was probably made in Xi’an in present-day Shaanxi Province, China (Freer Gallery of Art, F1930.51), while the cup below is the Sogdian Fluted Cup.

The Sogdian-inscribed piece is a silver-gilt plate showing a mounted hunter with a ram’s-horn headdress, fighting boar. Most likely made in the eastern part of the Sasanian Empire, in the former Kushan realm of Bactria (present-day northern Afghanistan), it bears in Sogdian the name of an owner and its weight. See Prudence O. Harper, Silver Vessels of the Sasanian Period: Volume One, Royal Imagery (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1981), pl. 23.

Boris I. Marschak [Marschak/Maršak], Silberschätze des Orients: Metallkunst des 3.–13. Jahrhunderts und ihre Kontinuität (Leipzig: E. A. Seemann, 1986), 103.

Boris I. Marshak [Marschak/Maršak], “132. Set of Wine Vessels and a Tray,” in China: Dawn of a Golden Age, 200–750 AD, ed. James C. Y. Watt. (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art; New Haven, CT, and London: Yale University Press, 2004), 252–53.

Map showing the “Silk Roads” running east–west and the various “Fur Routes” that headed to northern parts of Asia.

Map showing the possible routes running west from Sogdiana to reach Constantinople while avoiding the Sasanian Empire.

Cup with Goats. Ancient region of Sogdiana, 8th century CE. Gilded silver; H. 7.3 cm × W. 12 cm. The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, S-251.

Photograph © The State Hermitage Museum.

Silver and Gilt Plate Showing the Siege of a Castle

Sogdian, 9th–10th century

Cast, engraved, and gilded silver; Diam. 23.7 cm

Found in 1909 near village of Anikova, Perm Province , Russia

The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, S-46

Photograph © The State Hermitage Museum

Sogdian Banqueters. Panjikent, Tajikistan (ancient Sogdiana), Site XVI:10, first half of 8th century. Wall painting; H. 136 cm × W. 364 cm. The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, SA-16215-16217.

Photograph © The State Hermitage Museum.

Banqueters. Panjikent, Tajikistan (in ancient Sogdiana), Site XXIV:1, first half of the 8th century CE. Wall painting; H. 94 x W. 192 cm (left), and H. 107 x W. 105 cm (right). The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia, SA–16235.

Photograph © The State Hermitage Museum.

Ewer. Ancient Sogdiana, ca. late 7th–early 8th century CE. Gold; H. 30.5 cm. Moscow, State Historical Museum. OK 14083.

Photograph courtesy of Daniel C. Waugh.

Winged Camel Ewer. Ancient Sogdiana, late 7th–early 8th century CE. Gilded silver; H. 39.7 cm. The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, S-11.

Photograph © The State Hermitage Museum.

Phoenix-Headed Ewer. Tang dynasty (618–906 CE), from a Tang tomb. Polychrome lead glazes over buff earthenware with molded relief decoration. H: 31 cm. Gansu Provincial Museum, Lanzhou 兰州.

After Annette L. Juliano and Judith A. Lerner, Monks and Merchants: Silk Road Treasures from Northwest China (New York: Harry N. Abrams and Asia Society Museum, 2001), 316, no. 111.

Chinese wine cup of the Tang period (late 7th century CE) and a Sogdian cup (7th century CE). The Chinese example (F1930.51) follows the general outline of its Sogdian prototype (F2012.1) but is more compact and has a simpler ring. Its body, however, is more elaborate. Instead of the abstract S-shapes of the Sogdian vessel, the Chinese one is covered with chased and ring-punched designs of wildlife cavorting among grapes and foliage.

Freer Gallery of Art, F1930.51 (left) and F2012.1 (right).

Lobed Bowl with Lion, Foliage Enclosed in a Medallion. Possibly Uzbekistan (in ancient Sogdiana), late 6th–early 7th century CE. Silver; H. 4.8 × Diam. 15.3 cm.

Purchase, Charles Lang Freer Endowment, Freer Gallery of Art, F1997.13.