Banqueting in Sogdiana

by Betty Hensellek

The Western Regions possess a grape wine which is not spoiled by the accumulation of years. A popular tradition among them states that it is drinkable up to ten years, but if you drink it then, you will be drunk for the fullness of a month, and only then be relieved of it.

—from the Taiping Yulan 太平御覽 (Imperial Readings of the Taiping Era), 977–983

And from this wine I immediately delivered three small containers of wine for that evening’s banquet.

—from the Sogdian Mt. Mugh Documents, early 8th century

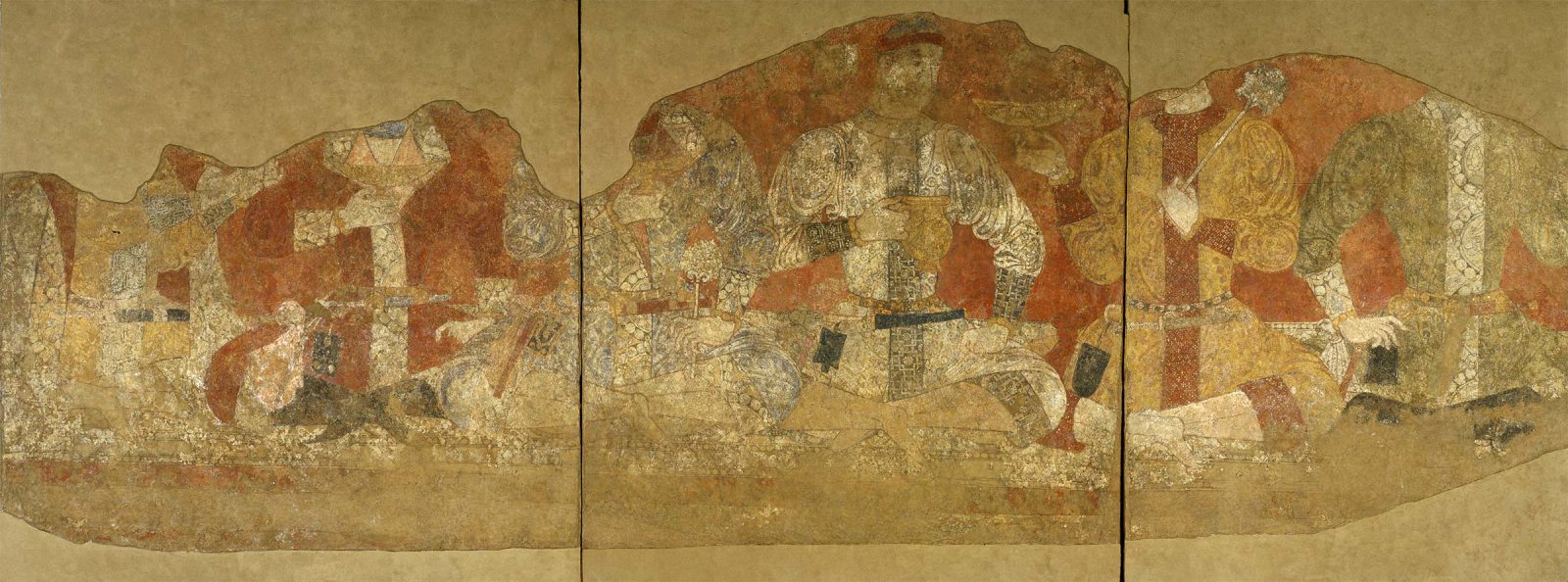

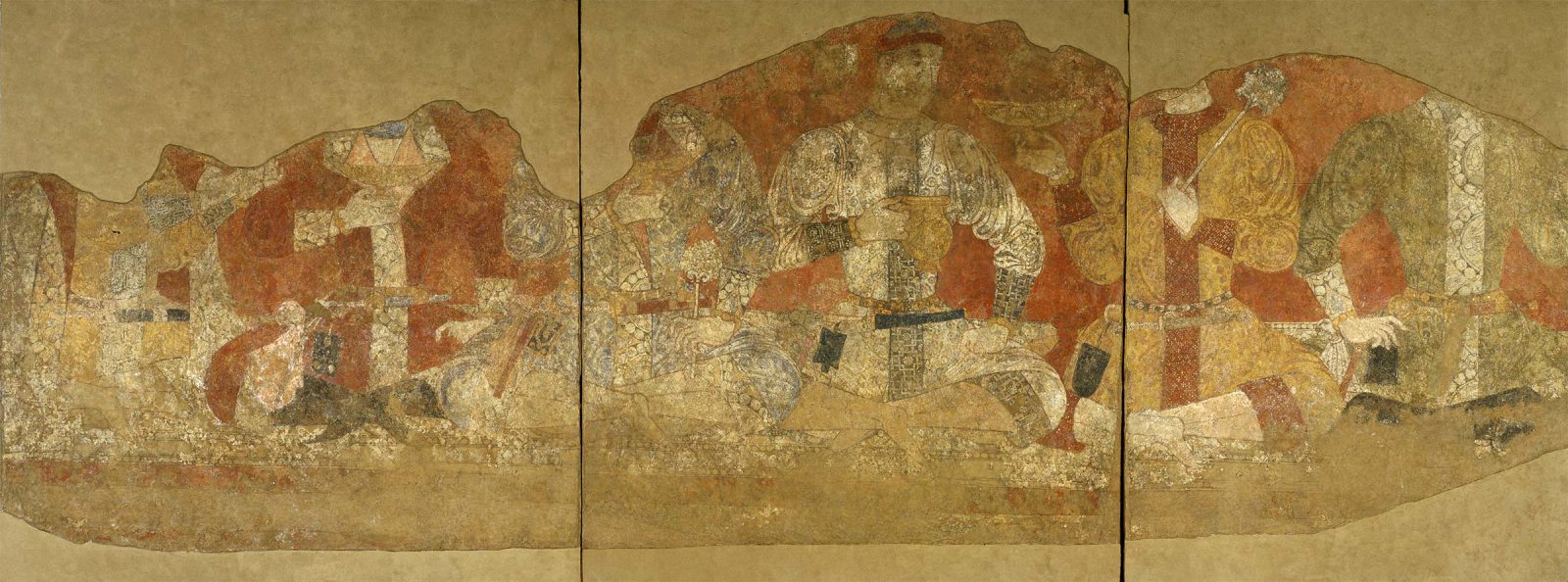

Sipping wine from gilt silver cups and dressed to the nines in vividly patterned kaftans, banqueters revel in convivial company amid beautifully decorated surroundings. Several wall paintings at Panjikent depict such vibrant social festivities, associated with a variety of occasions, both secular and sacred; Figs. 1 and 2. These paintings, along with actual metalwork, Figs. 3–5, and some Sogdian texts, provide us with a glimpse into the 8th-century Sogdian banquet. This essay explores the spaces in which these banquets were held, the refreshments served, and the vessels used, along with the appearance and etiquette of those attending the festivities.

Fig. 3 Cup with Goats. Ancient region of Sogdiana, 8th century CE. Gilded silver; H. 7.3 cm × W. 12 cm. The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, S-251. View object page

Photograph © The State Hermitage Museum.

Fig. 4 Fluted Cup with Ring Handle Decorated with Elephant Heads. Possibly Uzbekistan (in ancient Sogdiana), 7th century CE. Gilded silver; H. 6.3 x W. 8.9 cm. View object page

Purchase, Charles Lang Freer Endowment, Freer Gallery of Art, F2012.1.

Fig. 5 Winged Camel Ewer. Ancient Sogdiana, late 7th–early 8th century CE. Gilded silver; H. 39.7 cm. The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, S-11. View object page

Photograph © The State Hermitage Museum.

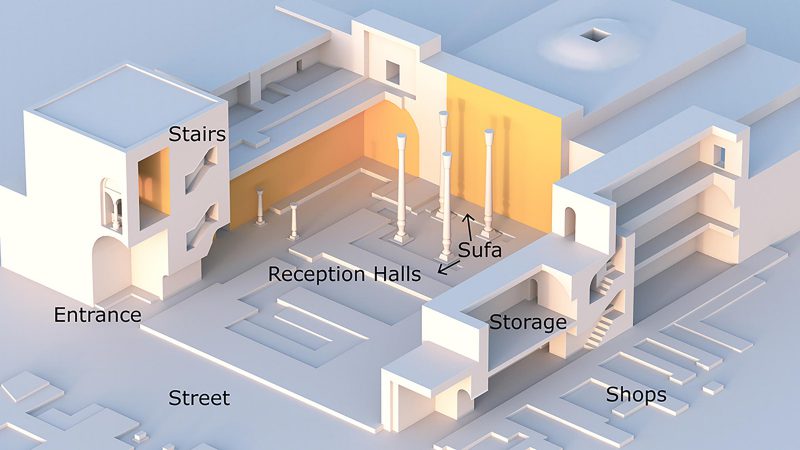

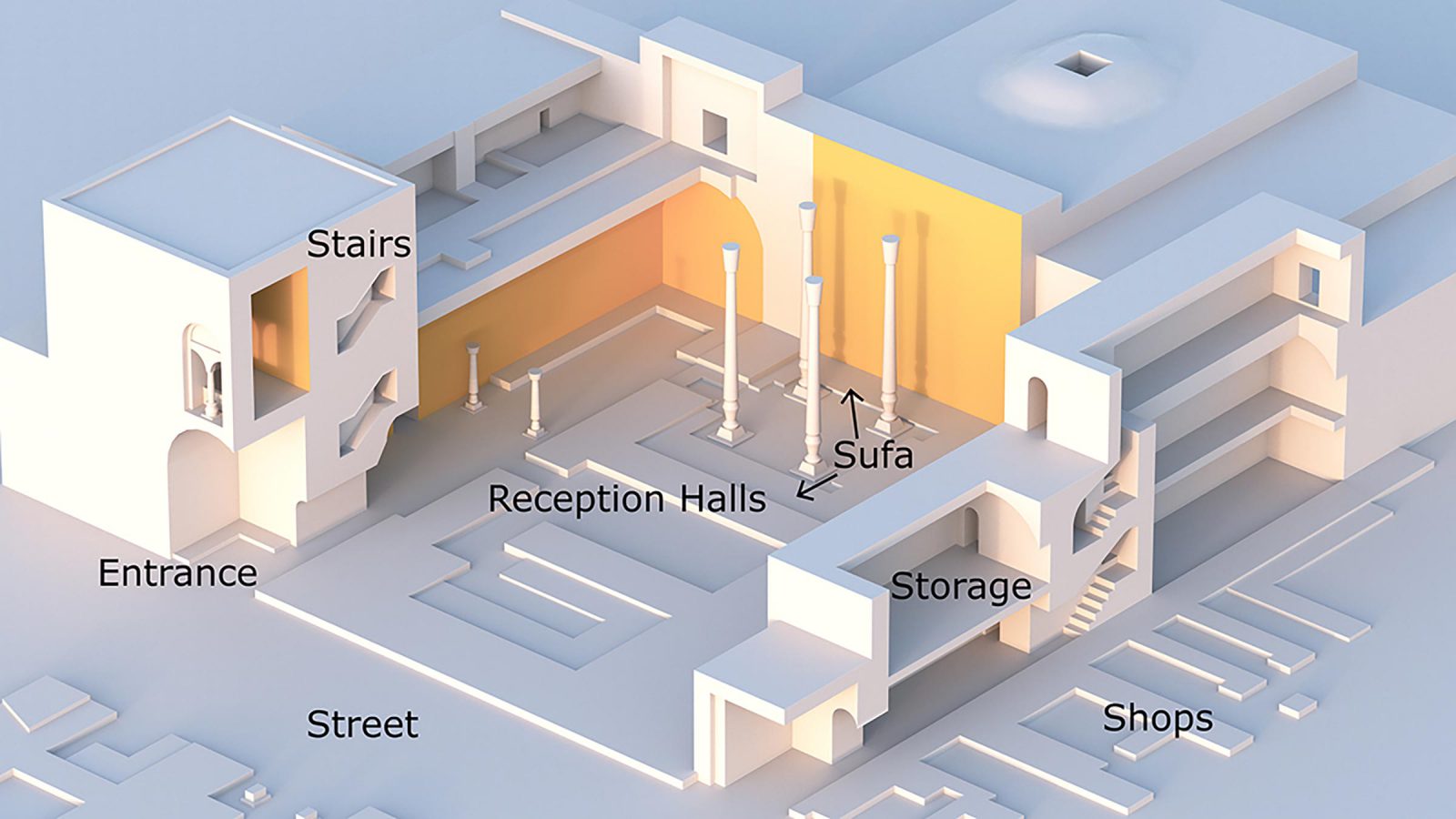

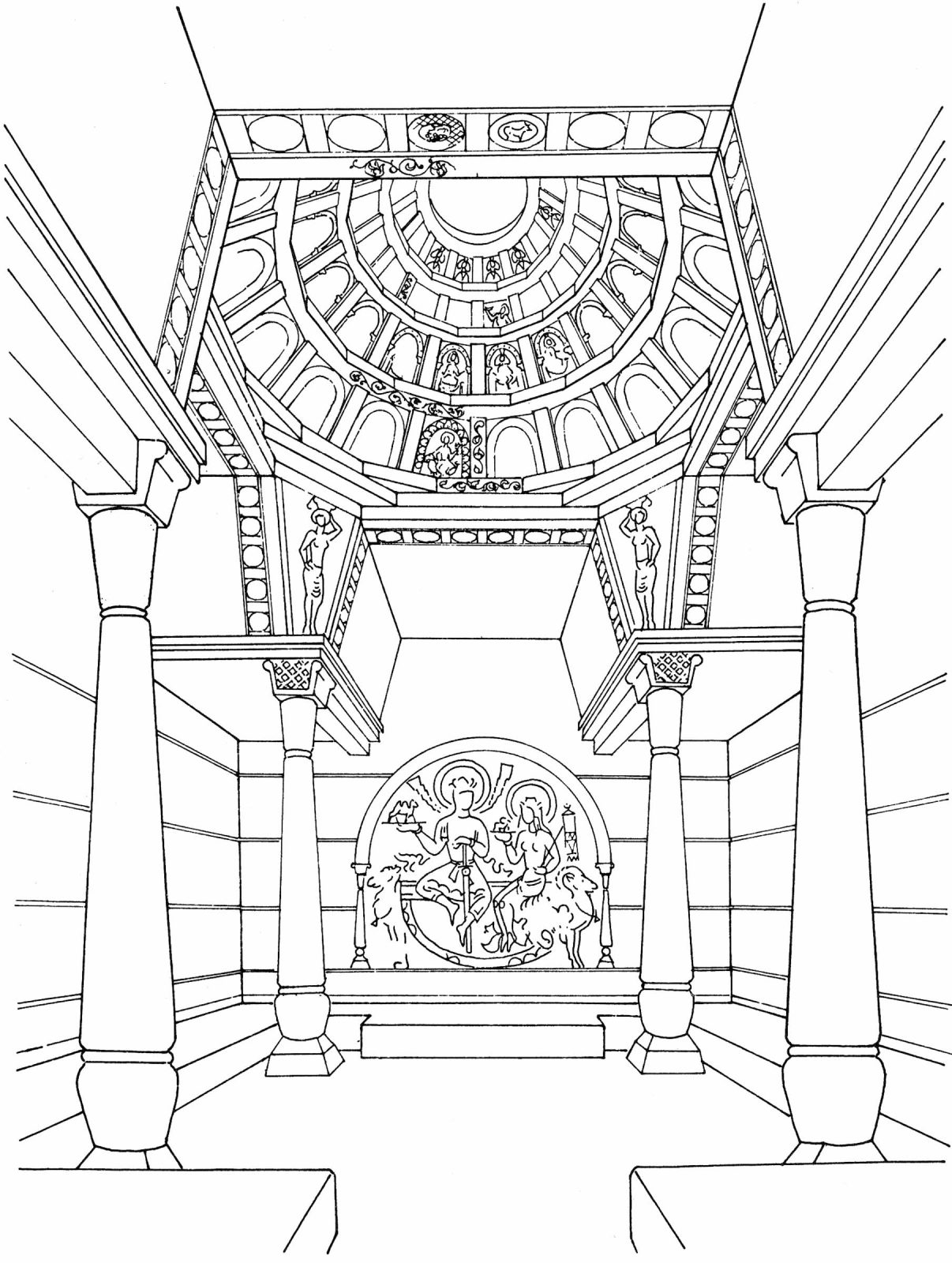

Where did Sogdians banquet?

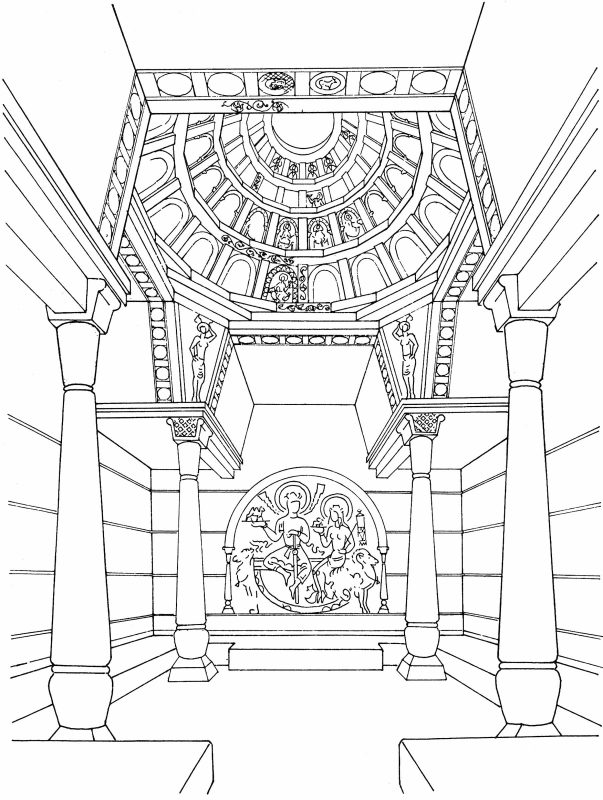

Sogdians built their homes with rooms for gathering with business associates, friends, and family, located directly off a main corridor. Guests could enter the home and arrive at these rooms without passing through more private familial spaces. Whether in a palatial or elite private residence, such rooms had a built-in bench (or sufa), constructed of plaster-covered clay, which ran around the entire room. The sufa, around 16 inches (approx. 40 cm) high and about 39 inches (1 m) deep, was covered with rugs; the rooms could accommodate between ten and thirty guests. At Panjikent and in greater Sogdiana, the most common type of room for holding banquets was the reception hall; Fig. 6. Seated, cross-legged guests could enjoy food laid out on the sufa, while the open center of the room allowed for servants to move about, alongside dancers and musicians; Fig. 7.

What did Sogdians eat and drink?

Sogdians indulged in wine at banquets. In the paintings at Panjikent, the stream of liquid flowing from drinking vessels is always red, and wine is the only beverage mentioned among other foodstuffs in the 8th-century Sogdian documents discovered at the Mount Mugh citadel. One document, written by a wine distributor, lists how many kapicha (a Sogdian measure) of wine had been delivered on specific days, including wine for an evening banquet that was held on the 28th day of the second month of the Sogdian calendar (equivalent to July 30th in the year of 720, 721, or 722). Another, a letter from Devashtich, Panjikent’s ruler, states that upon the arrival of his letter to the addressee, aromatic wine should be sent to the Turkic military commander. As in neighboring Iran, imbibing wine was central to the banquet; in fact, Chinese sources comment on the variety and potency of the wines produced in Central Asia and Iran.

From the wall paintings we see that banqueters enjoyed a variety of fruit, such as grapes, melons, and peaches. More substantial foods are not pictured, but a number of products—barley, wheat, oil, peas, and sheep meat—are mentioned in the Mount Mugh documents, and would have been part of the meals served.

Fig. 9 Fluted Cup with Ring Handle Decorated with Elephant Heads. Possibly Uzbekistan (in ancient Sogdiana), 7th century CE. Gilded silver; H. 6.3 x W. 8.9 cm. View object page

Purchase, Charles Lang Freer Endowment, Freer Gallery of Art, F2012.1.

What tableware did Sogdians use?

In addition to ceramic plates and vessels, elite Sogdians dined and drank from cups and bowls of silver, which were often gilded. Two distinctive types of personal cups are a small, shallow bowl without a handle (similar to the piala from which tea is drunk in Uzbekistan and Tajikistan today; Fig. 8), and a cup with a small ring handle (one subtype looking much like a modern teacup; Fig. 9). The shallow bowls are between 10 and 20 cm in diameter, and are typically decorated with fluting or vegetal designs. Sogdian craftsmen liked to engrave an animal or a vegetal design at the bottom so that as the drinker drained the bowl, the image would emerge from the liquid. The ring-handled cup, typically 6 to 9 cm in height, is distinctive for its ornamented thumb rest and variety of exterior decoration; Figs. 10 and 11.

Fig. 10 Cup with Goats. Ancient region of Sogdiana, 8th century CE. Gilded silver; H. 7.3 cm × W. 12 cm. The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, S-251. View object page

Photograph © The State Hermitage Museum.

Fig. 11 Detail of the Cup with Goats: Thumbrest. View object page

Photograph © The State Hermitage Museum, S-251.

A larger, communal vessel is the rhyton, which must have enlivened the Sogdian banquet; Fig. 12. Horn-shaped, its narrow end terminates in an animal’s head, from which the liquid pours into the drinker’s open mouth. Several paintings show banqueters drinking from a ram-headed rhyton . Servants could pour the wine from tall, bulbous-bodied ewers; Fig. 13.

Fig. 13 Winged Camel Ewer. Ancient Sogdiana, late 7th–early 8th century CE. Gilded silver; H. 39.7 cm. The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, S-11. View object page

Photograph © The State Hermitage Museum.

Larger serving bowls and plates with lobed or radiating embossed shapes were particularly well suited for stacking fruits and other foods; Figs. 14 and 15.

Fig. 14 Lobed Bowl with Lion, Foliage Enclosed in a Medallion. Possibly Uzbekistan (in ancient Sogdiana), late 6th–early 7th century CE. Silver; H. 4.8 × Diam. 15.3 cm. View object page

Purchase, Charles Lang Freer Endowment, Freer Gallery of Art, F1997.13.

What to wear and how to behave at a Sogdian banquet

On taking a seat on the cushioned sufa, guests would have met the eyes of fellow banqueters, but also those of the painted banqueters on the walls. The idealized guests in these paintings illustrate what guests were expected to wear and how they were to behave, and also reflect their actual dress and behavior.

The wall paintings at Panjikent present two distinct types of banqueting festivities: a formal banquet and a drinking party. This distinction is based on sitting posture, the drinking vessels used, and the styling of the kaftans. The known Sogdian painting corpus confirms only men’s attendance at either kind of banquet, but in southern Uzbekistan (neighboring Tokharistan), wall paintings of formal banquets show that women actively engaged in this activity alongside men.

In the painting of a formal banquet, the banqueters seat themselves cross-legged at regular intervals from their fellow banqueters; Fig. 16. With upright posture, they turn their heads somewhat stiffly to converse. Some attendees hold a fly-whisk or fan, and each drinks from his own vessel. The men wear belted kaftans, which accentuate the idealized masculine body type of broad shoulders and a wasp-thin waist. Most attendees wear their kaftans closed, with the lapels turned up and buttoned closely around the neck. Only a few open the lapels of their kaftans and expose the contrasting-colored inner linings and tunics worn underneath. This social distinction of wearing the lapels pulled open corresponds to accessorizing with the most gold-encrusted adornments, as well as sitting farther forward than other attendees, as indicated by the wearer’s knees overlapping those of his neighbors.

In contrast, at the drinking party in Fig. 17, the banqueters sit in more relaxed postures, turning freely to their neighbors and moving their arms in animated conversation. Each sits farther apart from his neighbor and this spacing is often irregular, with servants, entertainers, or fruit dishes situated in between. Attendees do not hold and drink from individual vessels as do those at the formal banquet. Instead, they share a single vessel: the horn-shaped, animal-headed rhyton. As at the formal banquet, attendees wear kaftans, but there is a range of ways in which they are styled. These men wear their kaftans more casually, with either one or both lapels open, or even more informally, completely unbuttoned and with no tunic underneath.

Edward H. Schafer, The Golden Peaches of Samarkand: A Study of T’ang Exotics, quoting from T’ai-p’ing yü-lan [1892 edition] (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985), 144.

Document B-2 [Б-2], M. N. Bogolyubov and O. I. Smirnova, Sogdiyskie dokumenty s Gory Mug: Chteniye, perevod, i kommentariy, vypusk III, khozyaystvennye dokumenty Согдийские документы с Горы Муг: чтение, перевод и комментарий, выпуск III, хозяйственные документы [Sogdian Documents from Mount Mugh: Reading, Translation, and Commentary. Volume III, Economic Documents](Moscow: Eastern Literature Publishing House, 1963), 29–30 (author’s translation from the Russian).

For example, in XXV:28 Panjikent, a private residence, banqueters painted in the lower register of a room celebrate a successful harvest; see Boris I. Marshak [Marschak/Maršak] and Valentina I. Raspopova, “Wall Paintings from a House with a Granary, Panjikent, 1st Quarter of the Eighth Century A.D.” Silk Road Art and Archaeology 1 (1990): 123–76. In contrast, painted on the walls of a small room associated with Panjikent’s Temple I is what seems to be a more sacred religious festivity; see A. Yu. Yakubovskiy, M. M. D’yakonov, A. M. Belenitskiy, and P. I. Kostrov, Zhivopis’ drevnego Pandzhikenta Живопись древнего Панджикента [Paintings of Ancient Panjikent] (Moscow: Nauka Publishing House, 1954), pls. 9 and 10.

A second type of room for gatherings—for example, XVI:10 at Panjikent—is termed a “chapel” or a “home sanctuary.” This room would share the architectural features of a built-in bench and an open central floor plan with the reception hall, but differences would include an entrance through a vestibule, a lower ceiling, and a niche atop a podium in place of a painted deity wall.

Document B-2 [Б-2], M. N. Bogolyubov and O. I. Smirnova, Sogdiyskie dokumenty s Gory Mug: Chteniye, perevod, i kommentariy, vypusk III, khozyaystvennye dokumenty Согдийские документы с Горы Муг: чтение, перевод, и комментарий, выпуск III, хозяйственные документы [Sogdian Documents from Mount Mugh: Reading, Translation, and Commentary. Volume III, Economic Documents] (Moscow: Eastern Literature Publishing House, 1963), 29–31. My thanks to Frantz Grenet for supplying the Gregorian calendar date. See also Frantz Grenet and Boris I. Marshak, “Le mythe de Nana dans l’art de la Sogdiane,” Arts Asiatiques, 53 (1998): 5–18, especially page 6, for a discussion of a festival, which began on July 30 and lasted seven days.

Document A-16 [A-16], Vladimir A. Livshits [Livšic], Sogdian Epigraphy of Central Asia and Semirech’e, ed. Nicholas Sims-Williams, trans. Tom Stableford. Vol. III, Corpus Inscriptionum Iranicarum,, Part II, Inscriptions of the Seleucid and Parthian Periods and of Eastern Iran and Central Asia (London: School of Oriental and African Studies, 2015), 115–18.

For wine consumption and banqueting in Iran, see Touraj Daryaee, Sasanian Persia: The Rise and Fall of an Empire (New York: I. B. Tauris, 2013), 51. For Chinese views on Iranian and Central Asian wines, see Edward H. Schafer, The Golden Peaches of Samarkand: A Study of T’ang Exotics (Berkeley, London, and New York: University of California Press, 1985), 144.

For instance, grains are mentioned in documents Б-8 [B-8] and Б-20 [B-20]; peas in Б-8 [B8]; meat in Б-11p [В-11R]; and fruits in Б-13 [B-13]. See M. N. Bogolyubov and O. I. Smirnova, Sogdiyskie dokumenty s Gory Mug: Chteniye, perevod, i kommentariy, vypusk III, khozyaystvennye dokumenty Согдийские документы с Горы Муг: чтение, перевод и комментарий, выпуск III, хозяйственные документы [Sogdian Documents from Mount Mugh: Reading, Translation, and Commentary. Volume III, Economic Documents] (Moscow: Eastern Literature Publishing House, 1963).

Ceramic vessels come from excavated sites in Sogdiana. For a comprehensive study of the ceramic corpus of Sogdiana in the 5th–7th centuries, see Boris. I. Marshak [Marschak/Maršak], Keramika Sogda V–VII vekov kak istoriko-kul’turnyy pamyatnik (k metodike izucheniya keramicheskikh kompleksov) Керамика Согда V–VII веков как историко-культурный памятник (к методике изучения керамических комплексов) [Sogdian Ceramics of the 5th–7th Centuries as Historical and Cultural Phenomenon (On the Methods of the Study of Pottery Complexes)] (St. Petersburg: The State Hermitage Publishing House, 2012). For a concise discussion of ceramic table-vessel types of Panjikent in the 8th century, see A[lexandr] M. Belenitskiy [Belenitskiĭ/Belenizki/Belenitski], I. B. Bentovich, and O. G. Bolshakov, Srednevekovyy gorod sredney Azii Средневековый город средней Азии [The Medieval City of Central Asia] (Leningrad: Nauka Publishing House 1973), 51–58, figs. 24–27.

Those in precious metals are found by chance, often in hoards, in areas outside of Sogdiana proper. For silverware of greater Late Antique Central Asia and Iran, see Boris I. Marshak [Marschak/Maršak], Silberschätze des Orients: Metallkunst des 3.–13. Jahrhunderts und ihre Kontinuität (Leipzig: E. A. Seemann 1986).

Boris. I. Marshak [Marschak/Maršak], Silberschätze des Orients: Metallkunst des 3.–13. Jahrhunderts und Ihre Kontinuität (Leipzig: E. A. Seemann 1986), pl. 67. Similarly shaped cups were made in Khwarezmia, pls. 86, 87; and several have been found in China, pls. 69, 112.

For an in-depth study of the formal banquet in Sogdiana according to the wall painting in XVI:10 Panjikent, see Betty Hensellek, “Banqueting, Dress, and the Idealised Sogdian Merchant” in Fashioned Selves, ed. Megan Cifarelli (forthcoming from Oxbow Books; Oxford, 2019). For an in-depth study on the drinking party according to several wall paintings from Panjikent see Betty Hensellek, “A Sogdian Drinking Game at Panjikent,” Iranian Studies, forthcoming. A subcategory of the formal banquet was a type set within a hallowed space and probably representing a sacred festivity. This type of banquet scene decorated Room 10 in the Temple I complex at Panjikent. See A. Yu. Yakubovsky, M. M. D’yakonov, A. M. Belenitsky, and P. I. Kostrov, Zhivopis’ drevnego Pandzhikenta Живопись древнего Панджикента[Paintings of Ancient Panjikent] (Moscow: Nauka Publishing House, 1954), pls. 9, 10.

The author is investigating the ways in which both men and women wore the kaftan for a formal banquet in Tokharistan according to the wall paintings from Balalyk Tepe in a future publication with the German Archaeological Institute.

See an in-depth study of this wall painting in Betty Hensellek, “Banqueting, Dress, and the Idealised Sogdian Merchant” in Fashioned Selves, ed. Megan Cifarelli (forthcoming from Oxbow Books; Oxford, 2019).

See an in-depth study of the Sogdian drinking party according to several wall paintings from Panjikent in Betty Hensellek, “A Sogdian Drinking Game at Panjikent,” Iranian Studies, forthcoming.

Sogdian Banqueters. Panjikent, Tajikistan (ancient Sogdiana), Site XVI:10, first half of 8th century. Wall painting; H. 136 cm × W. 364 cm. The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, SA-16215-16217.

Photograph © The State Hermitage Museum.

Banqueters. Panjikent, Tajikistan (in ancient Sogdiana), Site XXIV:1, first half of the 8th century CE. Wall painting; H. 94 x W. 192 cm (left), and H. 107 x W. 105 cm (right). The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia, SA–16235.

Photograph © The State Hermitage Museum.

Cup with Goats. Ancient region of Sogdiana, 8th century CE. Gilded silver; H. 7.3 cm × W. 12 cm. The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, S-251.

Photograph © The State Hermitage Museum.

Fluted Cup with Ring Handle Decorated with Elephant Heads. Possibly Uzbekistan (in ancient Sogdiana), 7th century CE. Gilded silver; H. 6.3 x W. 8.9 cm.

Purchase, Charles Lang Freer Endowment, Freer Gallery of Art, F2012.1.

Winged Camel Ewer. Ancient Sogdiana, late 7th–early 8th century CE. Gilded silver; H. 39.7 cm. The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, S-11.

Photograph © The State Hermitage Museum.

Reconstruction of a Panjikent house. Cut-away rendering of large house (Sector XXIV), Panjikent.

Courtesy of Alexander Brey.

Reconstruction of a reception hall of a Panjikent house, B. Marshak and E. Buklaeva.

After Boris Marshak, Legends, Tales, and Fables in the Art of Sogdiana (New York: Bibliotheca Persica Press, 2002), 16, fig. 10.

Detail, banqueter holding personal shallow, handleless cup. Panjikent, Tajikistan (in ancient Sogdiana), Site XVI:10, first half of 8th century CE. Wall painting; H. 136 × W. 364 cm. The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, SA-16215-16217.

Photograph © The State Hermitage Museum.

Fluted Cup with Ring Handle Decorated with Elephant Heads. Possibly Uzbekistan (in ancient Sogdiana), 7th century CE. Gilded silver; H. 6.3 x W. 8.9 cm.

Purchase, Charles Lang Freer Endowment, Freer Gallery of Art, F2012.1.

Cup with Goats. Ancient region of Sogdiana, 8th century CE. Gilded silver; H. 7.3 cm × W. 12 cm. The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, S-251.

Photograph © The State Hermitage Museum.

Detail of the Cup with Goats: Thumbrest.

Photograph © The State Hermitage Museum, S-251.

Banqueter Holding a Rhyton. Panjikent, Tajikistan (in ancient Sogdiana), Site XXIV:1, first half of the 8th century CE. Wall painting; H. 105 × W. 110 cm. The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia, SA–16235.

Photograph © The State Hermitage Museum.

Winged Camel Ewer. Ancient Sogdiana, late 7th–early 8th century CE. Gilded silver; H. 39.7 cm. The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, S-11.

Photograph © The State Hermitage Museum.

Lobed Bowl with Lion, Foliage Enclosed in a Medallion. Possibly Uzbekistan (in ancient Sogdiana), late 6th–early 7th century CE. Silver; H. 4.8 × Diam. 15.3 cm.

Purchase, Charles Lang Freer Endowment, Freer Gallery of Art, F1997.13.

Detail, Banqueters with Bowl of Fruit. Panjikent, Tajikistan (in ancient Sogdiana), Site XXIV:1, first half of the 8th century CE. Wall painting; The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia, SA–16235.

Photograph © The State Hermitage Museum.

Sogdian Banqueters. Panjikent, Tajikistan (ancient Sogdiana), Site XVI:10, first half of 8th century. Wall painting; H. 136 cm × W. 364 cm. The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, SA-16215-16217.

Photograph © The State Hermitage Museum.

Banqueters. Panjikent, Tajikistan (in ancient Sogdiana), Site XXIV:1, first half of the 8th century CE. Wall painting; H. 94 x W. 192 cm (left), and H. 107 x W. 105 cm (right). The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia, SA–16235.

Photograph © The State Hermitage Museum.