Seal and Its Impression

Double- portrait stamp-seal and impression, with Sogdian inscription of owner’s name.

Ancient Sogdiana, 4th–6th century CE

Carnelian; H. 3.3 × W. 2.6 cm

The British Museum, London, 1870.1210.3.

Photograph © Trustees of the British Museum

Engraved semiprecious stones (and other materials that can be carved in intaglio) have been used since the late 4th millennium BCE in the ancient world. Used for both personal and administrative purposes, seals helped to authenticate, identify, and secure documents, packages, and other property. Seal ownership protected not only property but the individual who owned it, for it could serve as an amulet, offering defense through the image or text engraved on the seal. It was also a mark of prestige.

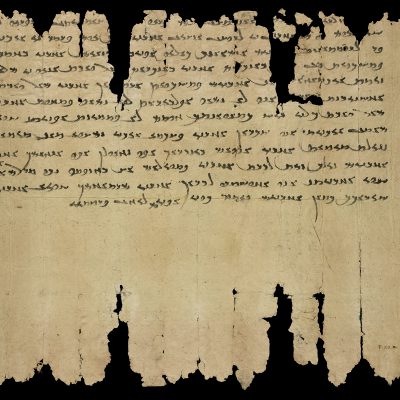

Thus it is not surprising that a mercantile society such as the Sogdians’ used seals. From Mount MughThe Castle on Mount Mugh and Its Documents Learn more about Mount Mugh we possess two clay impressions from such signets, each still attached to the document it once closed; Fig. 1.

Fig. 1 Seal impression of male head with Sogdian inscription, still attached to document it secured, B-4. Mount Mugh, Panjikent (in modern-day Tajikistan), before 722 CE. Unbaked clay with cord of parchment strip. Institute for Oriental Studies of Russian Academy of Sciences, St. Petersburg.

After Wilfried Seipel, Weihrauch und Seide: Alte Kulturen an der Seidenstrasse (Vienna: Kunsthistorisches Museum, 1996), 299, no. 165.

Other Sogdian sites have yielded a number of clay sealings that had been detached from whatever they had secured and been purposely saved. Relatively few Sogdian seal stones, however, have survived. An exception is this carnelian seal with a double-portrait bust of a man and a woman, each wearing an elaborate headdress and jewelry. He sports a pointed beard that grows from the edge of his chin or just under it, as do the beards of several kings depicted in the paintings at Panjikent . The couple’s flamboyant appearance contrasts with the profile male head on the Mount Mugh sealing: short beard, precisely curled hair, simple upper garment, and a pearl earring; Figs. 2 and 3. By no means a “true” portrait, the Mugh sealing nonetheless conveys a sense of how this individual might have looked. In contrast, the intaglio emphasizes the couple’s nobility not only by their dress but by the Sogdian inscription engraved above their heads: “This gem is from (the property of the) Indian mistress (or “princess, empress”) Nandy.” It is possible, though, that the inscription was added to the stone sometime between the 4th and 6th centuries, and that the intaglio itself is earlier.

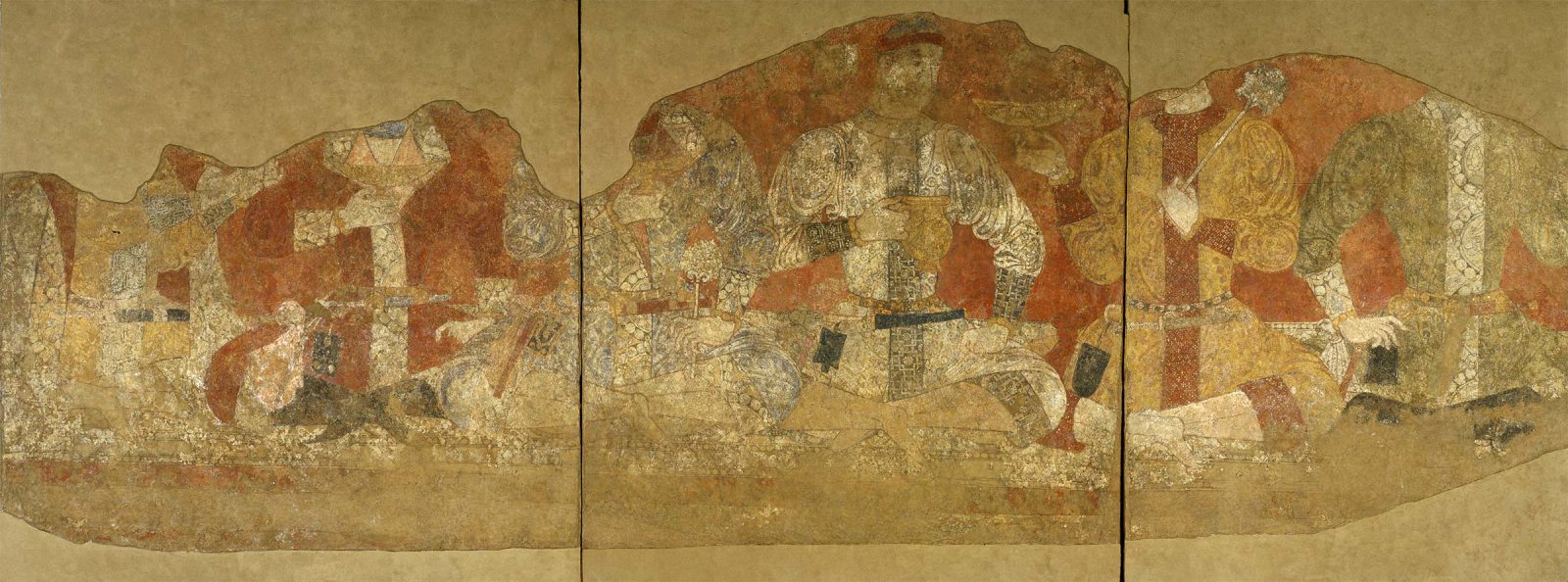

As they appear on the seal, the facial features of the couple are naturalistic. So, too, are those of the sender of the Mount Mugh seal, the individuals shown on other Sogdian seals, and the Sogdians represented elsewhere, as in the Panjikent wall paintings; Fig. 4. This naturalism contrasts with Chinese caricatures of Sogdians, although the exaggerations of the latter are generally confined to portrayals of servants and grooms; Fig. 5.

One exception, however, is the merchant who presents his wares to the occupant of the Yidu tomb; Fig. 6.

by Judith A. Lerner

Fig. 6 Sarcophagus Panel Showing Tomb Owner with Attendant and Sogdian Merchant. Yidu 益都, Qingzhou 青州, Shandong Province 山東省, China, dated to 573 CE. Incised limestone; H. 135 × W. 98 cm. Qingzhou Municipal Museum.

Drawing after Jiang Boqin 姜伯勤, Zhongguo Xianjiao yishushi yanjiu 中国祆教艺术史研究 [A History of Chinese Zoroastrian Art] (Beijing, 2004).

Dominique Collon, ed., 7000 Years of Seals (London: British Museum Press, 1997).

S. Cazzoli and C. G. Cereti, “Sealings from Kafir Kala: Preliminary Report,” Ancient Civilizations from Scythia to Siberia 11, nos. 1–2 (2005): 133–64; V[ladimir] A. Livshits [Livšic], “Sogdian Sānak, a Manichaean Bishop of the 5th–Early 6th Centuries,” Bulletin of the Asia Institute, n.s. 14 (2000 [2003]): 47–54; V[ladimir] A. Livshits [Livšic], “Sogdian Gems and Seals from the Collection of the Oriental Department of the State Hermitage,” in Exegisti Monumenta: Festschrift in Honour of Nicholas Sims-Williams, ed. Werner Sundermann, Almut Hintze, and François de Blois (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2009), 247–50, are a few of the publications of Sogdian seals and sealings.

The reading is by Livshits; see V[ladimir] A. Livshits [Livšic], “Sogdian Gems and Seals from the Collection of the Oriental Department of the State Hermitage,” in Exegisti Monumenta: Festschrift in Honour of Nicholas Sims-Williams, ed. Werner Sundermann, Almut Hintze, and François de Blois (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2009), 248. See also Judith A. Lerner, “Some Thoughts on a Sogdian Double Portrait Seal,” in Commentationes Iranicae: Vladimiro f. Aaron Livschits nonagenario donum natalicium, ed. Sergius Tokhtasev and Paulus Luria, Commentationes Iranicae: Sbornik statey k 90-letiyu V. A. Livshitsa, Pod red Под ред. С. Р. Тохтасьева и П. Б. Лурье, Сборник статей к 90-летию В. А. Лившица (Collection of articles for the 90th anniversary of VA Livshits, Ed.)] (St. Petersburg: Nestor-Istorija, 2013), 326–34.