Believers, Proselytizers, & Translators

Religion among the Sogdians

by Judith A. Lerner

The Sogdians were as open, varied, and eclectic in their religious practices as in their arts. This essay explores the role of Sogdians as believers, translators, and transmitters of religious ideas both in Sogdiana and farther afield.

The great discoveries of archaeological sites and artifacts over the course of the 20th century have transformed our understanding of religious life along the Silk Roads. They have also allowed us to build an increasingly detailed picture of religion in the ancient Iranian culture of Sogdiana, whose influence stretched far beyond its geographical boundaries. Perhaps the most striking feature of these discoveries is the sheer variety of beliefs that existed in Sogdiana: Mazdaism (Zoroastrianism), Hinduism, Buddhism, Christianity, Shaivism, Judaism, and Manichaeism. This suggests that the Sogdians brought the same sense of tolerance, openness, and creativity to their practices of religion as they did to their arts. At times they created dizzying combinations of different religious beliefs and imagery, and they drew on varied traditions, depending on need and opportunity. Here, we first set out a broad overview of the variety of religious practices for which we have evidence, focusing on their pluralism and syncretism—that is, their ability to tolerate and incorporate different beliefs within their communities. In doing so, we also note the crucial role of Sogdians as translators and transmitters of religious ideas and texts across tracts of the Silk Roads.

Mazdaism: The Primary Religion of Sogdiana

Any discussion of Sogdian religious life must start with the dominant and most widely practiced: Zoroastrianism, or more precisely, Mazdaism, after the deity Ahura Mazda (“All-Knowing Lord”), whom the Sogdians called Adhvagh. Mazdaism is a dualistic religion, that is, a belief in two supreme, opposed powers. Zoroastrianism is the more generally recognized name today, but actually it is a form of Mazdaism that was institutionalized as the official religion in neighboring Sasanian Iran. In Zoroastrian/Mazdean belief, Good (Ahura Mazda and his divine forces) is in perpetual battle with Evil (Ahriman and his followers). Through these two supreme opposing powers, the world was made. The conflict of Ahura Mazda and Ahriman also plays out through the opposition of purity and pollution. Mazdaism holds that the elements—fire, water, earth, and wind—are sacred and pure, and great care is taken not to pollute them in both religious rituals and daily life. Indeed, some have claimed this to be the first ecological religion. Of the four elements, fire, the source of light, represents truth and wisdom. Thus the fire altar plays a central role in religious ceremonies, such as the Afrinagan rite, in which celebrants offer incense, fruit, eggs, water, flowers, and other products of the earth’s bounty to Ahura Mazda.

The religion had its roots in eastern Iran and Central Asia, and at least some of its practices may date to the end of the third millennium BCE in Central Asia. By the early centuries of the first millennium CE, Mazdaism had already become the state religion of the Sasanian empire, and it was widely practiced in Sogdiana. Sogdian wall paintings offer us glimpses of the ways Sogdian Mazdaism could vary from Zoroastrianism. In the “Mourning Scene” from Temple II in Panjikent , Fig. 1, for example, the women we see in the pavilion wail and tear their hair, which Zoroastrianism would have prohibited. According to its tenets, such shows of emotion allow evil to enter.

Ossuaries: Protecting the Sacred Elements

Some of the richest sources for understanding Mazdaism as practiced in Sogdiana are ossuaries: lidded containers, usually of ceramic, used for storing the bones of the deceased. They have been discovered in different regions of Sogdiana (as well as at sites elsewhere in Central Asia, such as Chorasmia and Semirechye ). Ossuaries were necessary to Mazdaism, which was concerned with keeping away contamination and disease. In Mazdean belief, once life had left the body, it was defenseless against decomposition, which was viewed as the work of a demon. Following the proper prayers and offerings, Sogdian community members would transport the corpse to barren ground or a dakhma (an open-air platform often known as a “tower of silence”) and leave the body exposed to birds of prey. Burial or cremation practices were avoided in Mazdaism, for they would pollute the earth and fire, respectively. When the bones of the deceased had been defleshed, they would be gathered and placed in an ossuary.

Fig. 2 Ossuary. Mulla Kurgan (near Samarkand, Uzbekistan), ca. 7th century. Baked clay; 52 × 28 × 69 cm. Samarkand State Museum of History, Art and Architecture. View object page

After Sarah Stewart, ed., The Everlasting Flame: Zoroastrianism in History and Imagination (London and New York: I. B. Tauris, 2013), 100, pl. 36.

Fig. 3 Detail, lower part of the Ossuary from Mulla Kurgan: Two Mazdaean Priests Perfoming the Afrinagan Ceremony. Samarkand State Museum of History, Art and Architecture. View object page

Image courtesy of Frantz Grenet.

Over the centuries, ossuaries became increasingly ornate, illustrating Mazdean deities and religious practices. One such example from the 8th century is a stamped clay ossuary from Mulla Kurgan , Fig. 2, found not far from Samarkand . On the front, before a stepped fire altar from which leaves appear to sprout, are two priests. One stands with bellows or tongs to keep the fire going, while the other, holding short barsom bundles or sticks, kneels to recite the ancient liturgy. They may be officiating at the Afrinagan ceremony, performed on the morning of the fourth day after death—an appropriate subject for an ossuary; Fig. 3. The lower part of each face is protected by a mouth covering (padam), worn so that breath and spittle will not defile the sacred fire. Several interpretations have been offered for the single and paired female figures that decorate the pyramidal roof. They seem to be dancing, perhaps an indication that this upper portion of the ossuary represents the heavenly plane, as the joys of Zoroastrian paradise include music, song, and dance.

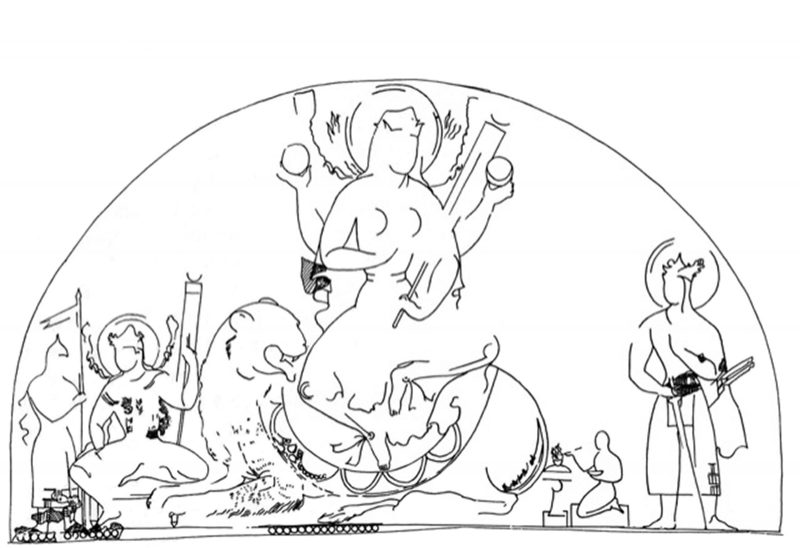

Other decorated ossuaries provide further insight into Sogdian conceptions of the afterlife. From the Shahr-i Sabz oasis south of Samarkand comes one that illustrates the weighing of the soul by Rashn, the god of justice; with the deities Mihr and Srosh, he judges the soul’s worthiness to cross the Chinvat Bridge into paradise; Figs. 4 and 5.

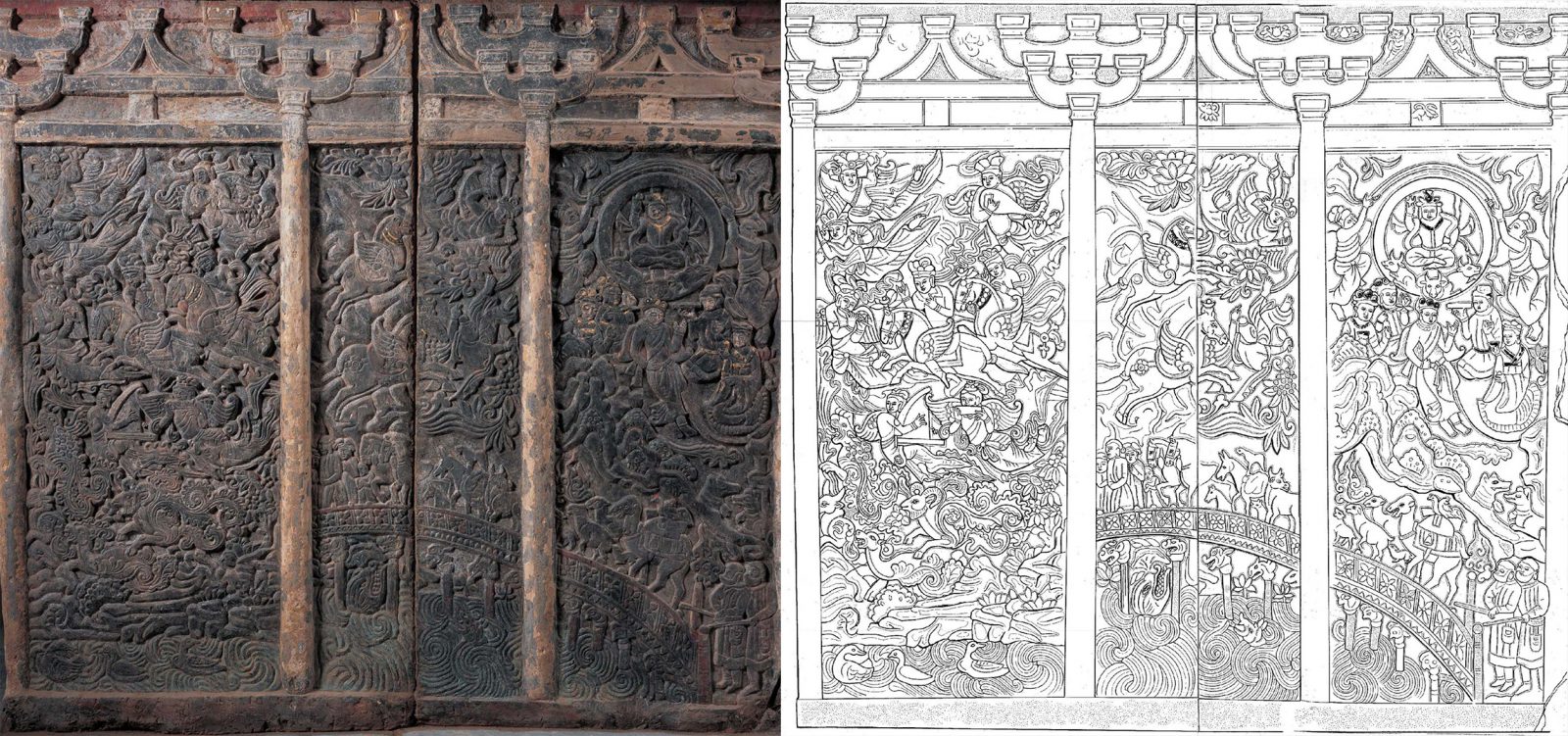

This crossing appears, too, on a house-shaped sarcophagus (which functions like an ossuary) excavated in Xi’an, Shaanxi province . The occupant, a man of Sogdian descent named Wirkak (or Shi Jun 史君), was a leader (sabao 薩保) of one of the Sogdian communities there. The three carved panels that form the eastern wall of the sarcophagus show the passage of the deceased (with his family) to the Zoroastrian or Mazdean heaven; Fig. 6.

Reading from right to left, the lower register shows the entrance to the bridge, guarded by two dogs and two priests. Wirkak with his wife, Wiyusi, and their children cross the bridge, accompanied by a caravan (perhaps a reference to Wirkak’s mercantile life). On the other side is a rocky landscape, described in a Sasanian Zoroastrian text as “a mountain over which the soul ascends” to reach the celestial garden that is paradise.

Wirkak’s soul has already been weighed, so the bridge is wide enough for him and his party to pass. Had his life and deeds been wanting, the bridge would have narrowed to razor thinness and Wirkak would have plunged into hell, depicted below as churning waters inhabited by monstrous creatures. According to a 9th-century post-Sasanian Zoroastrian text, on reaching the Chinvat Bridge, the soul of the deceased would encounter the embodiment of its thoughts, words, and deeds—the dēn. If these had been good, the dēn would be a radiantly beautiful young woman and would escort the deceased across the bridge, to the top of the mountain, and into paradise. (If the soul were to fail its weighing, the dēn would appear as an ugly hag.) In the upper right of the first panel of Wirkak’s sarcophagus, the dēn, a winged woman, is already in the heavenly realm and welcomes the couple. In the upper part of the other two panels, the god Mithra’s chariot (drawn by winged horses) bears them heavenward to the music of a celestial orchestra.

While illustrating various widely held beliefs from Mazdaism, this sarcophagus also provides a rare glimpse into how this religion was practiced in Sogdiana, whose rich culture brought together both West Asian and South Asian traditions. In the same panel we see a god who presides over heaven, seen beneath a billowing scarf held by two attendants; Fig. 7.

Fig. 7 Detail of east wall of Sarcophagus of Shi Jun (Wirkak) and Wiyusi: The Wind God Weshparkar. Excavated in Xi’an, Shaanxi Province, China, dated to 579–80 CE. Stone relief with traces of pigment and gilding; H. 1.58 × L. 2.45 × D. 1.55 m. Shaanxi History Museum, China. View object page

Image courtesy of Shaanxi Provincial Institute of Archaeology. Drawing after Xi’an Municipal Institute for the Conservation of Cultural Relics and Archaeology, “Xi’an Bei Zhou Liangzhou Sabao Shi Jun mu fajue jianbao,” fig. 27.

One might expect this to be Adhvagh (the Sogdian counterpart of Ahura Mazda). However, this deity sits on reclining bulls, holding a trident, neither of which is an attribute of Adhvagh/Ahura Mazda. Rather, here we seem to have a representation of the ancient Iranian god of wind and air, Vayu (Sogdian: Weshparkar), as the billowing veil would suggest, but he has the additional attributes of the Hindu god Shiva Maheshvara. The Iranian Vayu has been conflated with the Indian Shiva; iconography and belief from varied traditions have been fused to create something distinctively Sogdian.

Still another instance of ossuary usage may be among Jews who lived in Sogdiana. It is now widely accepted that ossuaries were a part of funerary practice among wealthier members of Jewish society in Roman Palestine. Yet Jewish adherents in Central Asia may have followed such secondary burial customs as well, as this essay will discuss.

Sogdian Pluralism and the Goddess Nana

The ease with which Sogdian religious practice incorporated elements of other traditions is clear in the figure of the goddess Nana. No discussion of the Sogdian pantheon, religion, and deities would be complete without her, even though her cult seems to have little (if anything) to do with Mazdaism. Of Mesopotamian or Babylonian origin, Nana’s worship has been attested in the Eastern Iranian lands of Parthia, Bactria, and Sogdiana since at least the first millennium BCE. It most likely entered Eastern Iran during the Hellenistic period or even earlier, when the region was under Achaemenid rule. It was not until the Kushans controlled northwestern India and adjoining regions, however, that Nana acquired her distinctive visual identity as a young woman with halo, typically with a diadem and crescent moon on her head and seated on a lion.

Fig. 8 Sogdian rock inscriptions. Shatial, Pakistan, 3rd–7th century CE.

Photograph after Nicholas Sims-Williams, Sogdian and Other Iranian Inscriptions of the Upper Indus, Section II.I, Plate 10b (1989) of Vol. III, Sogdian, in Part II, Inscriptions of the Seleucid and Parthian Periods and of Eastern Iran and Central Asia, of Corpus Inscriptionum Iranicarum (London: School of Oriental and African Studies [SOAS]).

While there is no evidence that the Kushans ever ruled in Sogdiana, this originally nomadic group seems to have exerted some degree of influence there, and Nana appears as an astral deity on the first copper coins struck in the Sogdian city of Bukhara . She rose to being patron goddess of the city of Panjikent and, to judge from Sogdian rock inscriptions in the Upper Indus River Valley route between Gandhara and Sogdiana, Figs. 8, to being one of the most revered deities of Sogdian merchants.

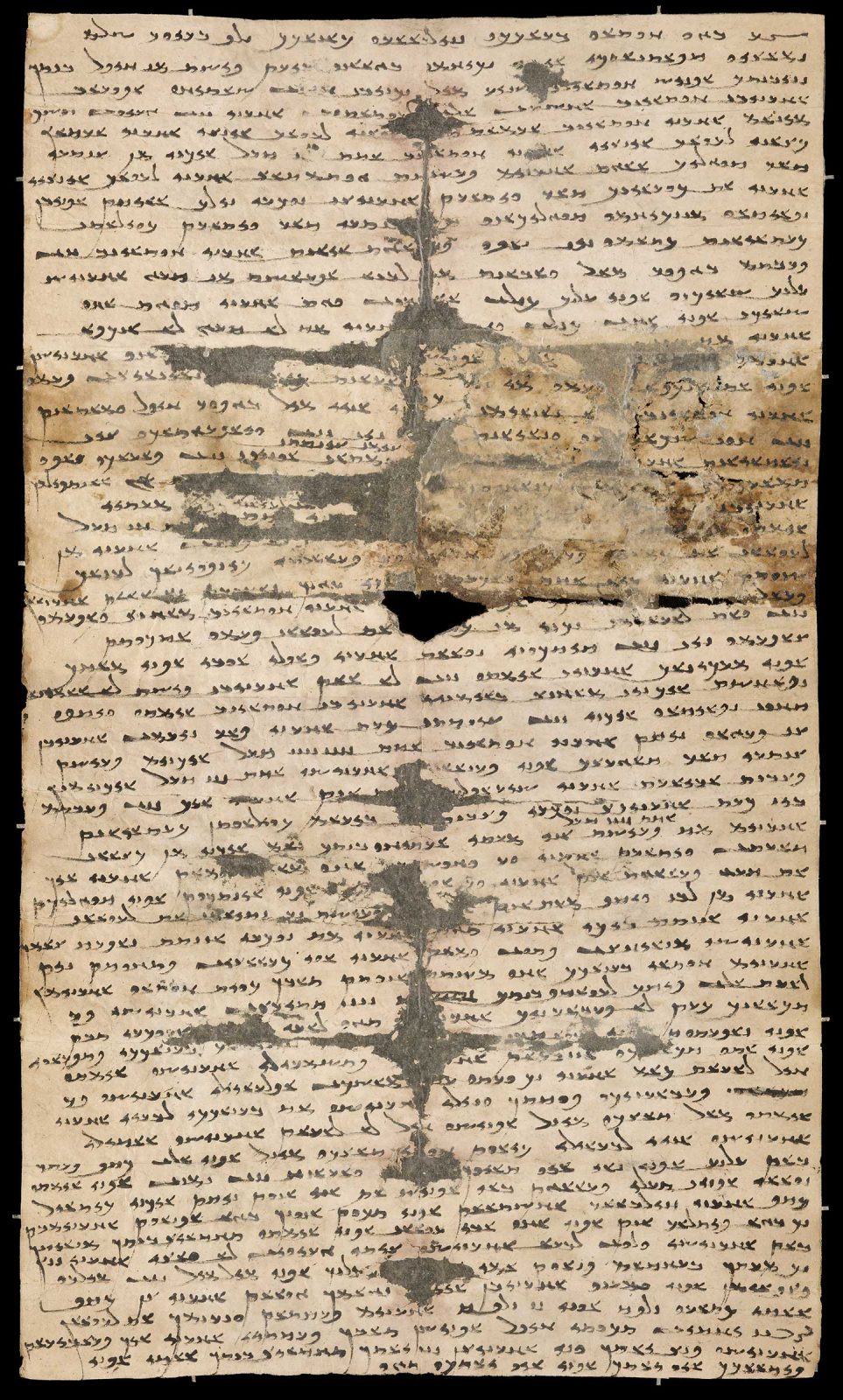

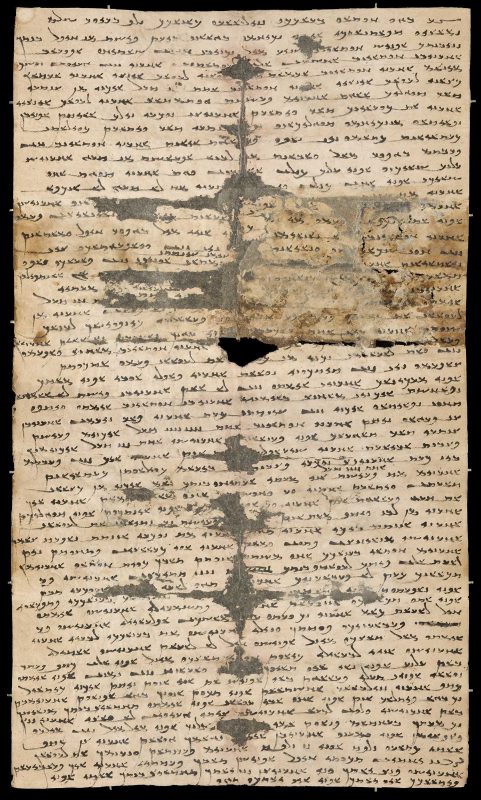

Fig. 9 Sogdian Ancient Letter 2, 312 or 313 CE. Discovered in 1907 at watchtower (T.XII.A), west of Dunhuang 敦煌, Gansu Province, China. Ink on paper; H. 42 × W. 24.3 cm. The British Library, Or. 8212/95. View object page

Photograph © The British Library Board.

Indeed, several Sogdian personal names contain hers, such as that of Nanai-vandak, the writer of Sogdian Letter 2; Fig. 9. Temple II at Panjikent likely was dedicated to her, as pieces of several statues were found there, as well as several fragmentary paintings that show her seated on her lion mount; Fig. 10. These depictions follow an established iconography for Nana; in addition to the lion, she has four arms—another feature borrowed from Hindu representations of deities—and her upraised pair holds the sun and the moon. Temple II housed the Mourning Scene (previously mentioned) in its main hall, and the four-armed goddess there may well be Nana; Fig. 11. As the main deity of Panjikent and apparently of other Sogdian towns (if not all of Sogdiana), her image adorned the reception halls of several residents’ houses within the city.

Fig. 12 Battle between a Deity and Beasts of Prey. Red Hall, Palace at Varakhsha, Uzbekistan, late 7th–early 8th century CE. Wall painting; H. 163 × W. 902 cm. The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, SA-14658-14675. View object page

Photograph © The State Hermitage Museum.

Fig. 13 Shiva with Trisula. Sogdian, 7th–8th century CE. Room in a Panjikent house, VII/24. Sogdian, 7th-8th century. Painted wood panel; H: 154 x L:147 cm. The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg, V-2704. View object page

Photograph © The State Hermitage Museum.

Fig. 14 God Shiva with Goddess Parvati [together called Uma-Maheshvara], Seated on the Bull Nandi. Clay, gypsum. Temple II, Panjikent, Tajikistan. Early 8th century CE.

After National Museum of Antiquities of Tajikistan: The Album, ed. R. Masov, S. Bobomulloev, M. Bubnova (Dushanbe, National Museum of Antiquities: 2005), 170, pl. 2.

At times we find in Sogdiana not just the use of Indian models to represent homegrown Sogdian gods, but the actual representation of Indian gods. The most frequently depicted Indian deity at Panjikent is Shiva, who through his cosmic dance simultaneously creates and destroys the universe. From a room in a private house, for example, comes a wooden panel painted with the figure of the blue-skinned dancing Shiva dressed in a tiger skin; Fig. 13. At his feet, a diminutive couple in Sogdian garb kneel, he raising an incense burner and she bearing a sheaf of presumably aromatic herbs for the fire. More impressive—and remarkable—are the remains of a large clay statue showing the dhoti-clad Shiva sitting with his wife, Parvati, perched on his thigh, and both on his bull mount, Nandi; Fig. 14. Discovered in a separate chapel of Temple II (otherwise dedicated to Nana), the sculpture was installed at the beginning of the 8th century. The room in which it was placed was reoriented so that it could be entered only from the street, rather than through the temple entrance courtyard. We cannot know whether this represents beliefs of some native Panjikenters or those of a Hindu community residing there for commercial purposes. Either way, the representations of Shiva from Panjikent suggest the kind of pluralistic approach to religious belief common to Sogdiana at the time.

Translators of the Silk Road: Buddhism among the Sogdians and Its Spread, along with Christianity and Manichaeism

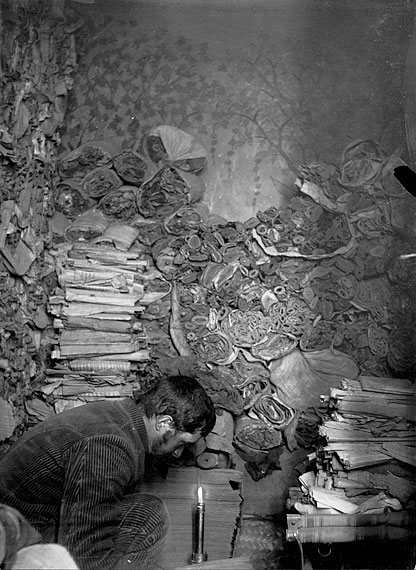

The picture painted of religion within Sogdiana and its communities along trading routes thus far suggests an ecumenical appreciation of various religious traditions, drawing on multiple sources and creating an idiosyncratic pantheon of gods. This all-embracing approach becomes further evident when we turn to the final section of this essay, which focuses on the role of Sogdians in the translation and transmission of religious texts and ideas from India and Central Asia to China. The discovery in the early 20th centuryMarc Aurel Stein Learn more about explorer and archaeologist Sir M. Aurel Stein of caches of documents in western China transformed our understanding of religion on the historic Silk Roads, Figs. 15–17, and of the ways that religious beliefs and texts spread among regions and cultures.

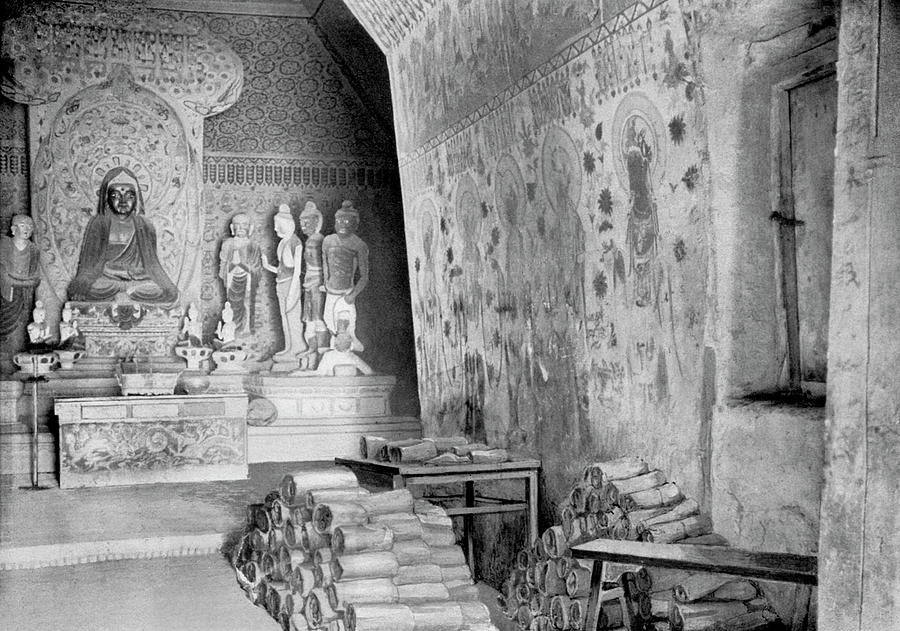

Fig. 15 Aurel Stein’s view of Mogao Cave 16, in Dunhuang 敦煌, Gansu Province 甘肅省, China, with a number of manuscripts from Cave 17 bundled on the floor.

After Aurel Stein, Serindia: Detailed report of explorations in Central Asia and westernmost China (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1932), vol. 2, fig. 200.

Fig. 16 Manuscripts in Qianfodong 千佛洞 (Cave of a Thousand Buddhas) at Dunhuang. The Library Cave contained some 15 cubic meters of manuscripts and paintings, dating from 406–1002 CE. Religious texts are mostly Buddhist, but include Manichean, Nestorian Christian, Daoist, and Confucian works. Secular documents offer glimpses of everyday life as well. The cave was likely sealed to protect records from invaders.

Photograph © Library of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Stein LHAS Photo 13/1 (56).

Fig. 17 Paul Pelliot examining manuscripts in Library Cave (Cave 17) at Dunhuang in 1908, a year after Stein’s expedition.

Charles Nouette Grotte 163. Niche aux manuscrits. Photograph © Musée Guimet, archives photographiques, AP8186.

A striking feature of these documents was how many were written in the Sogdian language, and often by Sogdians. With their mother tongue serving as the lingua franca of the trade routes, many Sogdians were able to speak multiple languages due to the necessities of trade, so they were ideally placed to act as transmitters of texts and ideas. We know now, for example, that some of the early translators of Buddhist scriptures were of Sogdian origin.

Sogdiana and the network of caravan trails stemming from Sogdiana to China also provided a key conduit for Buddhism to travel eastward. Having originated in northeastern India in the 6th century BCE, Buddhism rapidly spread throughout India and into Southeast Asia, parts of China, Tibet, Korea, and Japan. By the 1st century BCE, Buddhism was well established in Bactria (modern-day northern Afghanistan and southern Uzbekistan) and from there moved eastward into Sogdiana and other parts of Central Asia, then into the area that is now Xinjiang Autonomous Region and China proper; Fig. 18. Taking advantage of the established so-called northern and southern “Silk Routes” to carry their message, missionaries preached the dharma (the teaching of the Buddha) and translated Buddhist texts into local languages such as Khotanese, an Iranian tongue used by the inhabitants of Khotan , a major trading center on the southern route; Fig. 19.

The relative safety that Sogdian caravans offered to those plying the trade routes enabled these missionaries to carry their message eastward and also to move westward to India, seeking Buddhist texts to bring back to China and translate. Some missionaries left valuable accounts of their travels into these western territories, Sogdiana included. Among the most important was the 7th-century Chinese pilgrim XuanzangXuanzang Learn more about the Chinese Buddhist traveler Xuanzang, who on his way to India traveled through Sogdiana and left an important account of the people, cities, and events of the time.

The Sogdians and Christianity

Christianity was another religion that spread partly through Sogdiana and Sogdian hands. Soon after its inception, Christian belief spread quickly both westward and eastward via practitioners and is documented in Iran as early as the 4th century. In contrast to Judaism, Christianity is a religion that seeks new converts, and the network of trade routes through Central Asia and into China aided missionaries in spreading the new creed. In Iran, Central Asia, and China, the doctrine mostly followed the Syrian Church of the East (known in older literature as “Nestorianism”), which held that Christ was both Jesus the man and the Son of God. This contrasted with the Syrian Orthodox (in older literature, “Chalcedonian Christians”), who adhered to the resolutions of the Council of Chalcedon (451 CE) that in the person of Jesus Christ, divinity and humanity were united as one. Such Christians were a minority in these regions. A list of bishoprics compiled in 577 includes Samarkand , along with the Tarim Basin principality of Kashgar . Nothing survives of the episcopal cathedral of Samarkand, but at nearby Urgut —a site already known for its collection of East Syrian graffiti—archaeologists have excavated the remains of a monastic complex; presumably from Urgut, too, is a bronze thurible or censer featuring episodes in the life of Jesus Christ; Figs. 20–22.

Fig. 23 Dish Depicting Siege of a Castle. Uzbekistan or Tajikistan, 9th–10th century CE. Cast, engraved, and gilded silver; Diam. 23.3 cm. The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, S-46. View object page

Photograph © The State Hermitage Museum.

We also have evidence of Sogdian Christianity at Panjikent , where an ostracon (a potsherd used to write on) from the 7th or 8th century was found with portions of Psalms 1 and 2 in Syriac. Certain grammatical and spelling errors suggest that it was written from dictation, not by a Syrian, but by a Sogdian. Bukhara, too, seems to have had Christian inhabitants. Copper coins intended for local use were issued there with crosses on them. In fact, more coins with Christian symbols have been found around Bukhara than anywhere else in Central Asia, suggesting to Aleksandr Naymark that the issuing authority was Christian. Gilt silver plates with Christian themes also give evidence of Christian communities within Sogdiana itself or in its colonies to the east in Semirechye (now southeastern Kazakhstan and northern Kyrgyzstan). There the Church of the East apparently had more followers. All such plates, however, have been found beyond Sogdian territory, the result of trade transactions or booty. One from the village of Malaya Anikova in the Perm region of the Urals depicts Joshua’s siege of Jericho, Fig. 23, and is actually a copy made from a cast of an older plate that was recently found in northern Siberia; another silver plate, also found in the Perm region but at the village of Grigorovskoe , shows scenes related to the death and resurrection of Christ. If Christianity found some foothold in parts of Sogdiana, it also had a presence in the Sogdian language. Numerous Christian works in the East Syriac language were translated into Sogdian, with the greatest collection of these texts having been found at Turfan, on the northern Silk Route, and others in Dunhuang in western China; Fig. 24.

The Sogdians and Judaism

For the presence of Judaism in Sogdiana, there is indeed little, if any, material evidence. Instead, we must infer the presence of Sogdian Jewish communities from external conditions that go back to when the region was part of the Achaemenid empire. When the founder of the Achaemenid dynasty, Cyrus II (“the Great”; r. 553–ca. 529 BCE), captured Babylonia in 539 BCE, he allowed the Jews living in captivity there not only to return to Jerusalem to rebuild their temple, but to settle in other parts of the empire. It’s likely that some chose to move east with Cyrus’s conquests to live in his newly established Bactrian and Sogdian territories. Indeed, the biblical Book of Esther states that the Jews lived “in all the provinces” of the Empire.

Given the broad geographic spread of post-Exile Jewish communities, it is reasonable to assume that many embarked on overland trade, establishing a network from Babylonia to Iran and Central Asia and into China. Roman sources show that by the last centuries BCE, Palestinian and Babylonian Jews were participating in the silk trade from China; certainly, then, some resided in Sogdiana. Their only recognizable material remains, however, may be some ossuaries decorated with architectural or plant motifs. Aleksandr Naymark posits that these derive from the stone chests or ossuaries, already mentioned, that were used for secondary interment by some Jews during the Second Temple period (ca. 40 BCE–135 CE). Also suggesting the presence of Jews in Sogdiana are ossuaries with Hebrew inscriptions datable to the 6th and 7th centuries found at Merv , the northeastern outpost of the Sasanian empire. It is possible that the adoption of chestlike ossuaries with gabled roofs in Mazdean Sogdiana in the 5th or 6th centuries was at least partly inspired by this earlier Jewish practice. It is more likely, though, that persecution of Sasanian Jews (as well as Christians) by Shapur II (r. 309–379) and several of his successors caused some members of those groups to forgo burial and use ossuaries. Periodic Sasanian persecutions of non-Zoroastrians also prompted emigration to India. It is likely that others moved to more-tolerant Sogdiana and its colonies, such as Semirechye (southeastern Kazakhstan) and elsewhere, to the northeast.

The Sogdians and Manichaeism

Finally, the role of Sogdians as translators and transmitters is particularly striking when it comes to the religion of Manichaeism. Founded in Sasanian Mesopotamia by the prophet Mani (b. 216/7 CE near the capital, Seleucia-Ctesiphon in present-day Iraq), this new religion drew inspiration from Buddhism, Zoroastrianism, Judaism, and Christianity. Like Zoroastrianism (Mazdaism), and to some extent Christianity, Manichaeism was dualistic, based on the constant struggle between Good and Evil. It views the world and all within it as products of the opposition of these two powerful forces. Yet this “Religion of Light” is not so black-and-white—or “Manichaean”—as that term has come to connote. As Jason BeDuhn writes, “both light and darkness had ‘spiritual’ and ‘material’ aspects. Darkness was for Mani as much a motive force as it was a material [one], and the divine was present in the world as five substantial elements”—that is, air, wind, light, water, and fire.

Manichaeism was a mobile and syncretic religion, in some ways a natural fit for the culture-crossing Sogdian merchant communities. Mani traveled far as a missionary, and would adapt his message to the languages and concepts of the religions whose followers he strove to convert. Thus, although his religious roots were Judeo-Christian (rather, Elkhasaite, after one of the many sects of that time and place), his theology and cosmology seems to be Zoroastrian. The emphasis on monastic life and belief in the transmigration of the soul are to some extent Buddhist, although such connections with Buddhism are disputed. Nevertheless, Mani claimed to be Maitreya, the future Buddha who will appear on Earth and teach the pure dharma (Buddhist doctrine), according to the texts that describe his preaching in India (240–42 CE). In the West, Mani’s teachings were presented as a form of Christianity; in the East, they were portrayed as a form of Buddhism.

Figs. 25 and 26 Rock Crystal Seal of Manichaean Prophet Mani. Possibly Mesopotamia, Sasanian Dynasty, mid-3rd century CE. Carved rock crystal, H. 0.9 × Diam. 2.9 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, Inv. 58.1384bis.

After Zsuzsanna Gulácsi, “The Prophet’s Seal: A Contextualized Look at the Crystal Sealstone of Mani (216–276 CE) in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France.” Bulletin of the Asia Institute, n.s. 24 (2010 [2014]): 162, Pl. 4.

Although we have no archaeological evidence of Manichaeans in Sogdiana itself, Sogdian communities to the east (especially in the settlements in the Turfan oasis ) translated Manichaean texts, and many community members were themselves Manichaean. As A. K. Narain observes, “It was in Sogdiana that Manichaeism found its refuge when it was persecuted on all sides. Its syncretism found a good vehicle in the Sogdian merchant who traveled far and wide amidst people belonging to various religions and faiths.” An Arab source notes that Manichaeans were living in Sogdiana, particularly in Samarkand. When the Chinese pilgrim Xuanzang visited Samarkand in the seventh century, he met members of the community. At Kanka , southwest of modern Tashkent , not far from the banks of the Syr Darya, an important caravan stop on the southern caravan route, archaeologists found a number of clay seal impressions made by stone intaglios; one of the most popular among them is the image of a beardless man with a pageboy haircut, surrounded by an inscription; Figs. 25 and 26. Carved into the intaglio in reverse, the letters in the impression read, “[Manichaean] Bishop Sānak, son of Kawāt.” The letter shapes of the impression date the seal to no later than the 6th century—evidence of the spread of Manichaeism in the 5th and 6th centuries.

With their knowledge of many languages, the Sogdians, Manichaean or not, were the ideal translators of Manichaean texts from Syriac, Parthian, and Middle Persian into Turkish as well as Chinese. Indeed, Sogdian Manichaeans are credited with bringing the message of Mani to the Uighurs. In putting down the rebellion of An Lushan in China in 755, the Tang emperor was aided by the Turkic Uighurs. In the course of the conflict, the Uighur kaghan, or ruler, made the acquaintance of some Sogdian Manichaeans who converted him. In 763, the khaghan made Manichaeism the official religion of the Uighur state, and it remained so for almost a hundred years. Evidence of this remained unknown until the early 20th century. Then in 1905, in the cache of manuscripts in the “Library Cave” of , explorer-archaeologist Aurel SteinMarc Aurel Stein Learn more about explorer and archaeologist Sir M. Aurel Stein discovered Manichaean texts written in Old Turkish by Sogdian translatorsSogdian Language and Its Scripts Learn more about the Sogdian language.

Conclusion

Manichaean religious texts found in western China were written in several languages, including Sogdian and Uighur (Old Turkish)—many by Sogdian translators and scribes. Such objects neatly encapsulate the religious life of Sogdian culture. Sogdian religious practices were persistently plural, the product of interactions taking place across a broad swathe of the Eurasian landmass. This essay has attempted to give a sense of some of that diversity. At the same time, it has also made a case for certain salient features of Sogdian religious life that are recognizable across time and space. First of all is a religious pluralism that allowed the representation and worship of a pantheon of deities, from Ahura Mazda to Shiva to Jesus Christ, within a single milieu. Second is a frequent syncretism that drew on multiple sources and could repurpose models found in other traditions for the particular context of Sogdian culture. Third is the widespread role of Sogdians as translators, in the Latin sense of “carrying across” (trans + latus) one set of religious ideas and texts from a particular culture into another. In religion—just as in the trade of silks, furs, and other precious goods—the Sogdians played the role of middlemen par excellence.

Michael Shenkar, Intangible Spirits and Graven Images: The Iconography of Deities in the Pre-Islamic World. Series, Magical and Religious Literature of Late Antiquity, Vol. 4. (Leiden and Boston: Brill 2014), 63–64.

Greek and Chinese literary evidence exists for the Sogdians also exposing the dead to dogs. As an early 7th-century Chinese traveler writes of Samarkand, “Outside the city walls there is a separate community of over two thousand households who specialize in funerary matters. There is also a separate building in which dogs are kept. Whenever a person dies [members of this community] will go and collect the corpse and place it inside this building and order the dogs to devour it.” Tongdian 通典193.1039b, translated in Samuel N. C. Lieu, Manichaeism in the Later Roman Empire and Medieval China: A Historical Survey, 2nd ed., expanded and revised (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1985), 183.

Frantz Grenet, “Religious Diversity among Sogdian Merchants in Sixth-Century China: Zoroastrianism, Buddhism, Manichaeism, and Hinduism,” Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 27 (2007): 47.

Boris Ilich Marshak [Marschak], “Les Fouilles de Pendjikent.” Comptes rendus de l’Academie des Inscriptions et Belles Lettres (CRAI) 134, no. 1 (1990): 307–8.

Jodi Magness, “Ossuaries and the Burials of Jesus and James.” Journal of Biblical Literature 124, no. 1 (2005): 121–54.

Michael Shenkar, Intangible Spirits and Graven Images: The Iconography of Deities in the Pre-Islamic World, in Magical and Religious Literature of Late Antiquity series, vol. 4 (Leiden and Boston: Brill 2014), 116–28; Joan Goodnick Westenholz, “Trading the Symbols of the Goddess Nanaya,” in Religions and Trade: Religious Formation, Transformation and Cross-Cultural Exchange between East and West, ed. Peter Wick and Volker Rabens (Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2013), 167–98.

Frantz Grenet, “Iranian Gods in Hindu Garb: The Zoroastrian Pantheon of the Bactrians and Sogdians, Second-Eighth Centuries.” Bulletin of the Asia Institute, n.s. 20 (2006, 2010) :87–99.

The labels “Nestorian” and “Monophysite” are now considered derogatory, and many contemporary scholars do not use them out of respect for modern-day members of these groups. Scott Fitzgerald Johnson, “Silk Road Christians and the Translation of Culture in Tang China,” Studies in Church History 53 (2017): n. 6.

Aza Vladimirovna Paykova [Pajkova], “The Syrian Ostracon from Panjikant.” Le Muséon 92, nos. 1–2 (1979): 159–69.

Aleksandr I. Naymark [Naimark], “Christians in Pre-Islamic Bukhara: Numismatic Evidence.” In Annual Central Eurasian Studies Conference. Abstracts of Papers 1994–1996. Eds. Johan Elverskog and Aleksandr Naymark (Bloomington: Indiana University, 1996), 11–13. Naymark [Naimark], Aleksandr I. “Sogdiana, Its Christians and Byzantium: A Study of Artistic and Cultural Connections in Late Antiquity and Early Middle Ages.” PhD diss., Indiana University (2001).

Ian Gilman and Hans-Joachim Klimkeit, Christians in Asia before 1500 (Richmond/Ann Arbor: Curzon/University of Michigan Press, 1999), 214–16.

Pavel Lurje, and Kira Samosyuk, eds. Expedition Silk Road: Journey to the West. Treasures from the Hermitage (Amsterdam: Hermitage Amsterdam, 2014), 205.

Nicholas Sims-Williams, “Sogdian and Turkish Christians in the Turfan and Tun-Huang [Dunhuang] Manuscripts.” In Turfan and Tun-Huang: The Texts—Encounter of Civilizations on the Silk Route, ed. Alfredo Cadonna. Orientalia Venetiana, vol. 4 (Florence: Leo S. Olschki, 1992), 43–61. See also Nicholas Sims-Williams, Biblical and Other Christian Sogdian Texts from the Turfan Collection (Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols, 2014).

Bible, Book of Esther 3:6, 8; 8:5, 12, and 9:20.

A[leksandr] Naymark [Naimark], “Sledy yevreyskoy kul’tury v Sogde” Следы Еврейской Кул’туры в Согде [Traces of Jewish Culture in Soghd]. Vestnik Evreiskogo Universiteta Вестник Еврейского Университета [Bulletin of the Hebrew University] 11, no. 1 (1996): 75–83.

Jason BeDuhn, “Review of Richard C. Foltz, Religions of the Silk Road: Overland Trade and Cultural Exchange from Antiquity to the Fifteenth Century.” (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1999. Journal of Chinese Religions 29 (2001): 294–96.

A. K. Narain, “Indo-Europeans in Inner Asia,” in The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia, ed. Denis Sinor (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1990), 175–76.

The title translated here as “bishop” was a specific term (‘spsg) for a Manichaean bishop. Vladimir A. Livshits, “Sogdian Sānak, a Manichaean Bishop of the 5th–Early 6th Centuries.” Bulletin of the Asia Institute, n.s. 14 (2000, 2003): 47–54.