The Sogdians Abroad

Life and Death in China

by Julie Bellemare and Judith A. Lerner

Iranian whirling girl, Iranian whirling girl…

At the sound of the string and drums, she raises her arms,

Like swirling snowflakes tossed about, she turns in her twirling dance.

Whirling to the left, turning to the right, she never feels exhausted,

A thousand rounds, ten thousand circuits—it never seems to end…

Compared to her, the wheels of a racing chariot revolve slowly and a whirlwind is sluggish.

Iranian whirling girl,

You came from Sogdiana…

So runs a Chinese poem by the famed Tang-dynasty poet Bo Juyi 白居易 (772–846 CE), describing a Sogdian dancer at the imperial court. The Sogdian Whirl (huxuan wu 胡旋舞), as the dance was known, would become a phenomenon in China; Fig. 1. Bo Juyi’s poem describes the impact of this Sogdian cultural import, of how “officials and concubines all learned how to circle and turn.” Indeed, the dance’s influence reached all the way up to the emperor Tang Xuanzong 唐玄宗 (685–762 CE). The poem tells how the courtesan Yang Guifei 楊貴妃 “stole the ruler’s heart with her Sogdian Whirl.” You might even say that the Sogdian Whirl created a catastrophe of world-historical proportions. The Sogdian-Turkic general An Lushan 安祿山 (703–757 CE) became a favorite of Xuanzong due, in part, to his expertise in the dance, despite weighing more than 400 pounds. This not-so-tiny dancer’s rebellion against his emperor would bring the Tang dynasty to its knees. The An Lushan Rebellion, as it became known, would later be claimed as proportionally among the deadliest atrocities in human history.

Fig. 2 This 8th-century Chinese statue is testament to the popularity of Central Asian musicians, many of whom were Sogdians, in China. China, Tang dynasty (618–907 CE). Glazed earthenware; H. 58.4 cm. Excavated in 1957 from the tomb of Xianyu Tinghui, general of Yunhui, buried in western suburbs of Chang’an (Xi’an), dated to 723 CE. National Museum of China, Beijing.

Photograph © National Museum of China

If the Sogdian Whirl was perhaps the most visible and momentous of Sogdian exports to China during the Tang period (618–907 CE), it was by no means the only one. Since at least the early 4th century, Sogdians had been conducting business in China. For entrepreneurial Central Asians, China was a land of possibility, offering lucrative markets and jobs. Many Sogdians seized the opportunity, and found a home and a living in China in a variety of occupations—as traders, entertainers, craftsmen, scribes, translators, monks, soldiers, and military leaders; Fig. 2. Unfortunately for us, the evidence for these varied figures is patchy at best. For the non-elites, we must piece together fragments from various sources, and this is the work of the first part of this essay. For the Sogdian elites we have significantly more evidence, which is analyzed in the second part of the essay. We focus on two such Sogdians for whom we are able to construct quite a detailed picture of their biographies, lifestyles, and worldviews.

Non-Elite Sogdians in China

In terms of non-elite Sogdians in China, we are perhaps on firmest ground in trade, where sources in a variety of languages make it clear that Sogdians were very active on several paths of the Silk Roads, controlling much of the trade between Central Asia and China. Their business savvy was so well known in China that various sayings accrued around it. For example, as one Tang history put it,

When they [Sogdians] give birth to a son, they put honey on his mouth and place glue in his palms so that when he grows up, he will speak sweet words and grasp gems in his hand as if they were glued there… They are good at trading, love profit, and go abroad at the age of twelve. They are everywhere profit is to be found.

One such Sogdian trader abroad was Nanai-Vandak, whom we know of from the extremely precious cache of letters that Sir Aurel Stein Marc Aurel Stein Learn more about explorer and archaeologist Sir M. Aurel Stein discovered ninety kilometers west of Dunhuang in 1907. Nanai-Vandak acted as an agent somewhere in Gansu Province for his partners back in Samarkand . Such textual evidence for Sogdian traders in China is reinforced by visual evidence: a Chinese tomb sculpture (mingqi 明器, Fig. 3) depicts such a trader, bearing a sack and holding an ewer of Sogdian shape. From other visual as well as textual evidence, we know that Sogdians and their descendants also served as horse trainers and grooms in China.

Marc Aurel Stein Learn more about explorer and archaeologist Sir M. Aurel Stein discovered ninety kilometers west of Dunhuang in 1907. Nanai-Vandak acted as an agent somewhere in Gansu Province for his partners back in Samarkand . Such textual evidence for Sogdian traders in China is reinforced by visual evidence: a Chinese tomb sculpture (mingqi 明器, Fig. 3) depicts such a trader, bearing a sack and holding an ewer of Sogdian shape. From other visual as well as textual evidence, we know that Sogdians and their descendants also served as horse trainers and grooms in China.

The Sogdians’ mercantile role required proficiency in languages, and for this reason they also frequently worked as translators for the Chinese bureaucracy as well as transmitters of religious texts. Although most Sogdians were Mazdeans in religious practice, others were Buddhist, Hindu, Christian, or Jewish, and some even became Buddhist monks. One such was Kang Senghui 康僧會, the son of a Sogdian merchant living in what is today Hanoi, Vietnam. Kang Senghui himself did not enter China by way of the west–east overland route, but instead came by sea. He, along with other Sogdian Buddhists living in and outside of Sogdiana, helped spread Buddhism in China through their translations into Chinese of the Buddhist sutras, as well as by their preaching.

Still other Sogdians came as artisans and craftsmen—among them, no doubt, metalworkersSogdian Metalworking Learn more about Sogdian metalwork who brought new shapes and techniques to their Chinese counterparts. Almost all of these emigrés were anonymous, but we do know something of the 6th-century Sogdian artist Cao Zhongda 曹仲達, who was said to be “good at clay sculpture and in painting images of the Buddha” as well as of the “famous people of his time.” Unfortunately, it seems that none of his art has survived. Cao was particularly well known for rendering drapery so that it looked as if the clothes were “thin and transparent as if emerging from water.”

Elite Sogdians in China

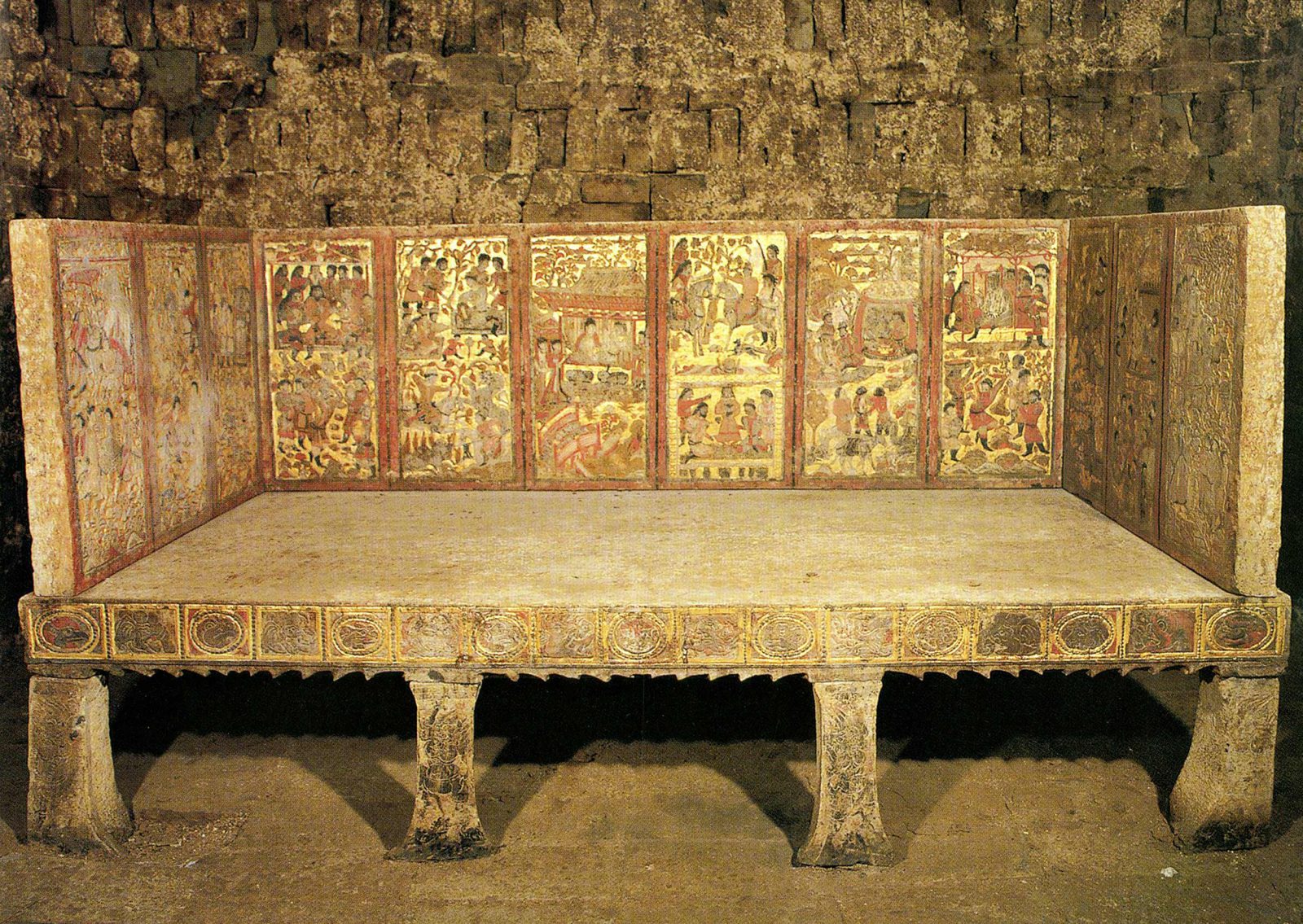

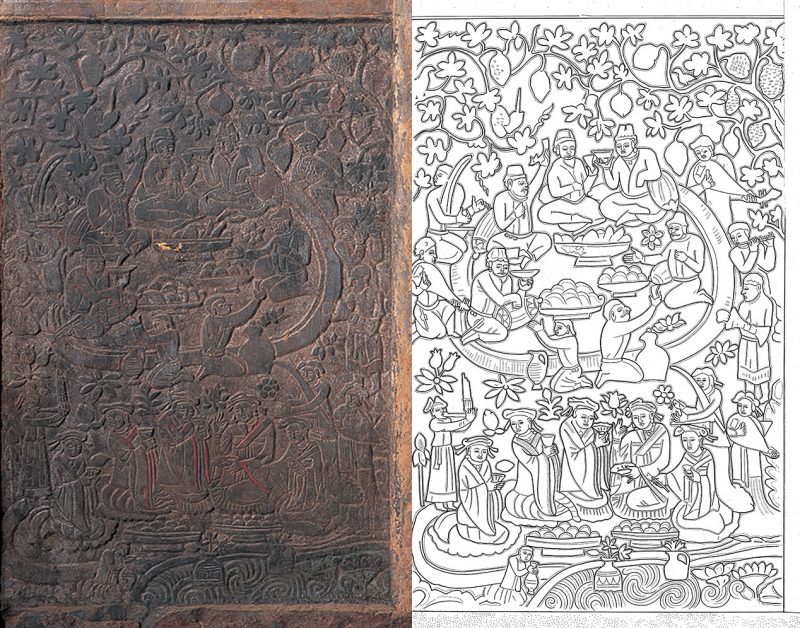

If the references to non-elite Sogdian traders, translators, and craftsmen in China remain highly fragmentary, we are more fortunate when it comes to members of the Sogdian elite. For here we are able to make use of a remarkably rich form of evidence: the tombstones and epitaph stones of several elite Sogdians found there over the last several decades. These elites were interred—sometimes with a wife, sometimes alone—in underground Chinese-style tombs, either on a stone Chinese-style bed or on a stone platform placed within a stone sarcophagus in the shape of a Chinese house; Figs. 4 and 5. Both beds and sarcophagi were elaborately decorated with carved, painted, and gilded scenes, typically depicting incidents from the life of the deceased as well as of the deceased (with family) feasting in paradise. Such scenes are atypical of Chinese tomb decoration but reflect the narrative quality of Sogdian art, as known from the 7th- and early 8th-century wall paintings found in Sogdiana itself, specifically at Panjikent .

Despite this, it is most likely that the carvers of these tombs were Chinese, not Sogdians, as the latter had no tradition of carving in stone. Their Chinese origin may go some way to explain the often caricatured representation of certain Sogdians featured on such tombs. Thus Sogdian entertainers and servants often appear as grotesques, with large noses and bulging eyes, as in this groom from the funerary bed of Kang Ye 康業, who was buried in Xi’an 西安 in 571 CE; Fig. 6.

Fig. 6 Detail of Funerary Bed of Kang Ye: Sogdian Groom. Excavated in Xi’an, China; dated to 571 CE. Incised stone; H. 73 × W. 29 cm. Xi’an Municipal Institute for the Conservation of Cultural Relics and Archaeology.

Drawing after Xi’an Municipal Institute for the Conservation of Cultural Relics and Archaeology 西安市文物保护考古研究院,“Xi’an Bei Zhou Kang Ye mu fajue jianbao 西安北周康业墓发掘简报 [Short excavation report of the Northern Zhou dynasty tomb of Kang Ye from Xi’an],” in Wenwu [Cultural Relics] 6 (2008): 14–35.

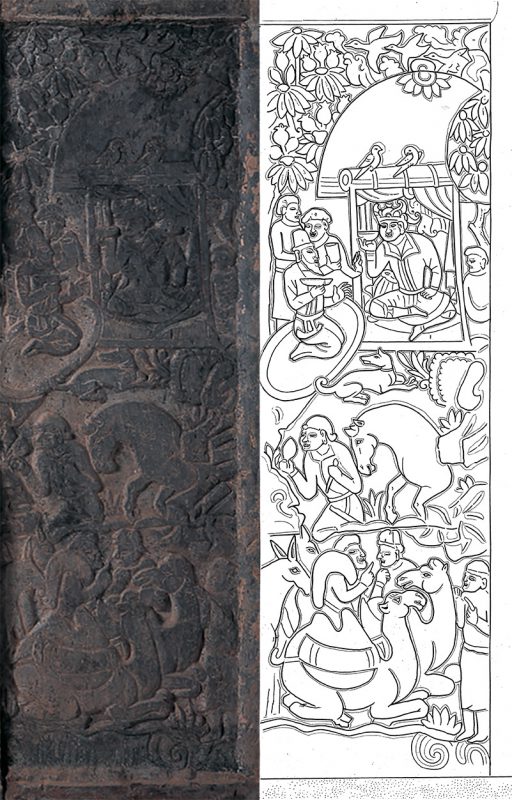

Fig. 7 Sarcophagus Panel Showing Tomb Owner with Attendant and Sogdian Merchant. Yidu 益都, Qingzhou 青州, Shandong Province 山東省, China, dated to 573 CE. Incised limestone; H. 135 × W. 98 cm. Qingzhou Municipal Museum.

Drawing after Jiang Boqin 姜伯勤, Zhongguo Xianjiao yishushi yanjiu 中国祆教艺术史研究 [A History of Chinese Zoroastrian Art] (Beijing, 2004).

Similarly, in this mid-6th-century incised slab that belonged to a sarcophagus found in Yidu 益都 , near Qingzhou 青州, Shandong Province, the tomb owner in elegant Chinese garb meets with a foreigner who crouches before him, offering some precious substance in a footed dish; Fig. 7. This person is most likely a merchant or trader: a Central Asian characterized (or caricatured) by his long nose, moustache, and curly hair; a Sogdian by his dress, with its rows of roundels—similar to those decorating the garments of the banqueters at Panjikent.

Of the several beds and sarcophagi that we have from these Sogdians, two of the most revealing were excavated in Chang’an 長安 (modern-day Xi’an) , the imperial capital and major terminus of the trade routes to China from the West. They belonged to An Qie 安伽 (b. 518 CE) and Shi Jun 史君 (b. 493 CE). Both men served in the bureaucracy of the ruling Northern Zhou dynasty (557–581 CE) as sabao 薩保, or leaders of their respective Sogdian communities. Both died in the same year, 579. The bed and sarcophagus offer a window onto the lives, values, and religious views of these elite Sogdians. Let us take these in turn; Fig. 8.

Fig. 8 Judith A. Lerner (Institute for the Study of the Ancient World, New York University) discusses the bed and sarcophagi of An Qie and Shi Jun.

Both An Qie’s bed and Shi Jun’s sarcophagus testify to the way Sogdian elites in China mediated and moved between the world of Central Asian merchants and Chinese bureaucracy. An Qie was born in Chansong 昌松 , near Guzang 姑藏 (modern-day Wuwei 武威, Gansu Province). Although his epitaph does not name grandparents, his surnameThe Nine Sogdian Surnames Learn more about the Chinese names for Sogdian families in China, An 安, points to ancestry from the Sogdian city of Bukhara , in present-day Uzbekistan. His father, Tujian 突建, was a military general (guanjun 冠軍) and prefectural governor of Meizhou 眉洲 (modern-day Meishan 眉山), in Sichuan Province. Shi Jun’s surname, Shi 史, tells us that his family was originally from Kesh (present-day Shahr-i Sabz, south of Samarkand, Uzbekistan). Actually, “Shi Jun” translates as “Master Shi” and we do not know his full Chinese name. His bilingual epitaph, however, tells us that his Sogdian name was Wirkak. At age twenty-six, Shi Jun married a woman from a similar background with the surname Kang 康, suggesting ancestry from the Sogdian city of Samarkand . From the Sogdian version of Shi Jun’s epitaph, we know that her Sogdian given name was Wiyusi. Together they had three sons, who built a lavish tomb for their parents after they both died only a month apart.

Shi Jun’s epitaph tells us that his grandfather was a sabao in their hometown of Kesh, serving as a kind of caravan leader for some of the many caravans that plied their way back and forth along the Silk Roads. The term sabao was most likely a translation of the Sogdian term s’rtp’w, itself derived from the Sanskrit sarthavaha, but similar words in several languages of South and West Asia make it difficult to pinpoint its origin. In Central Asia, it denoted the leader of a group of merchants and other individuals, such as entertainers, artisans, and pilgrims. It is likely that some aspects of this meaning carried over to Sogdian or Central Asian émigré communities in China. The role of sabao was to represent these local Central Asian communities by liaising with various levels of Chinese government. It is unclear whether communities nominated their own sabao and then the Chinese authorities confirmed them or the government directly dictated the appointments.

Both An Qie and Shi Jun served as sabao, just as Shi Jun’s grandfather had done. Despite holding the same office, though, the different duties they performed showcase the versatility of these community leaders and the way they could move among commercial, political, and military worlds. Shi Jun seems to have focused on commercial and political affairs. He began his official career at the age of forty-one as the chief of the Supervising Affairs section of the sabao bureau in Chang’an. He was later appointed sabao of Liangzhou 涼州 (modern-day Wuwei, in Gansu Province), an important center of trade due to its location on the Hexi Corridor (Hexi Zoulang 河西走廊), which funneled the overland traffic between the Tarim Basin (in Xinjiang ) and China.

An Qie, too, began his career as a sabao focused on trade and local affairs. An Qie’s epitaph states that he was selected by his community to be sabao of Tongzhou 同州, in modern-day Dali 大荔 , Shaanxi 陝西Province. Tongzhou’s strategic location at the western end of the pass called the Han’gu Guan 函谷關, connecting to Henan Province, made it important for the trade routes that extended northeastward from Chang’an. As sabao, An Qie oversaw local and commercial affairs, which included dealings with the Turks, who protected the Sogdian caravans as they traversed the often treacherous portions of the Silk Roads. Due to his success as sabao, An Qie was suddenly appointed Area Commander-in-Chief, or da dudu 大都督, a high military rank. It is likely that his promotion allowed him to command an armed division against the rival Northern Qi dynasty, which was ultimately defeated by the Northern Zhou in 577. Although An Qie died two years later, his epitaph states that his body “awaited a horse’s hide,” a reference to how a corpse was wrapped following death on the battlefield—a tribute to his prowess as a military commander.

Alongside biographical information, the tombs also illuminate the value systems of these elite Sogdians. Both tombs suggest a broadly shared conception of the “good life,” combining the imperatives of public service, the values of family life, and the pleasures of socializing. At the same time, the pictorial representations in their tombs reflect the diverse and individualized ways in which they chose to be portrayed—or in which their descendents chose to memorialize them. In An Qie’s case, his funerary bed resembles a Chinese chuang 床, a platform elevated on legs, enclosed on three sides by a screen and often covered by a canopy; Fig. 9.

Fig. 9 Funerary Bed of An Qie. Excavated in Xi’an, Shaanxi Province, China; dated to 579 CE. Gilded and painted stone relief; H. 1.17 × W. 2.28 × D. 1.3 m. Shaanxi Provincial Institute of Archaeology, Xi’an. View object page

After Shaanxi Provincial Institute of Archaeology 陕西省考古研究院, Xi’an Bei Zhou An Jia mu 西安北周安伽墓 [Tomb of An Jia from the Northern Zhou dynasty] (Beijing: Wenwu chubanshe, 2003), pl. 1.

A similar construction, with the addition of gateposts, is also found in Anyang 安陽 , in Henan Province; Fig. 10.

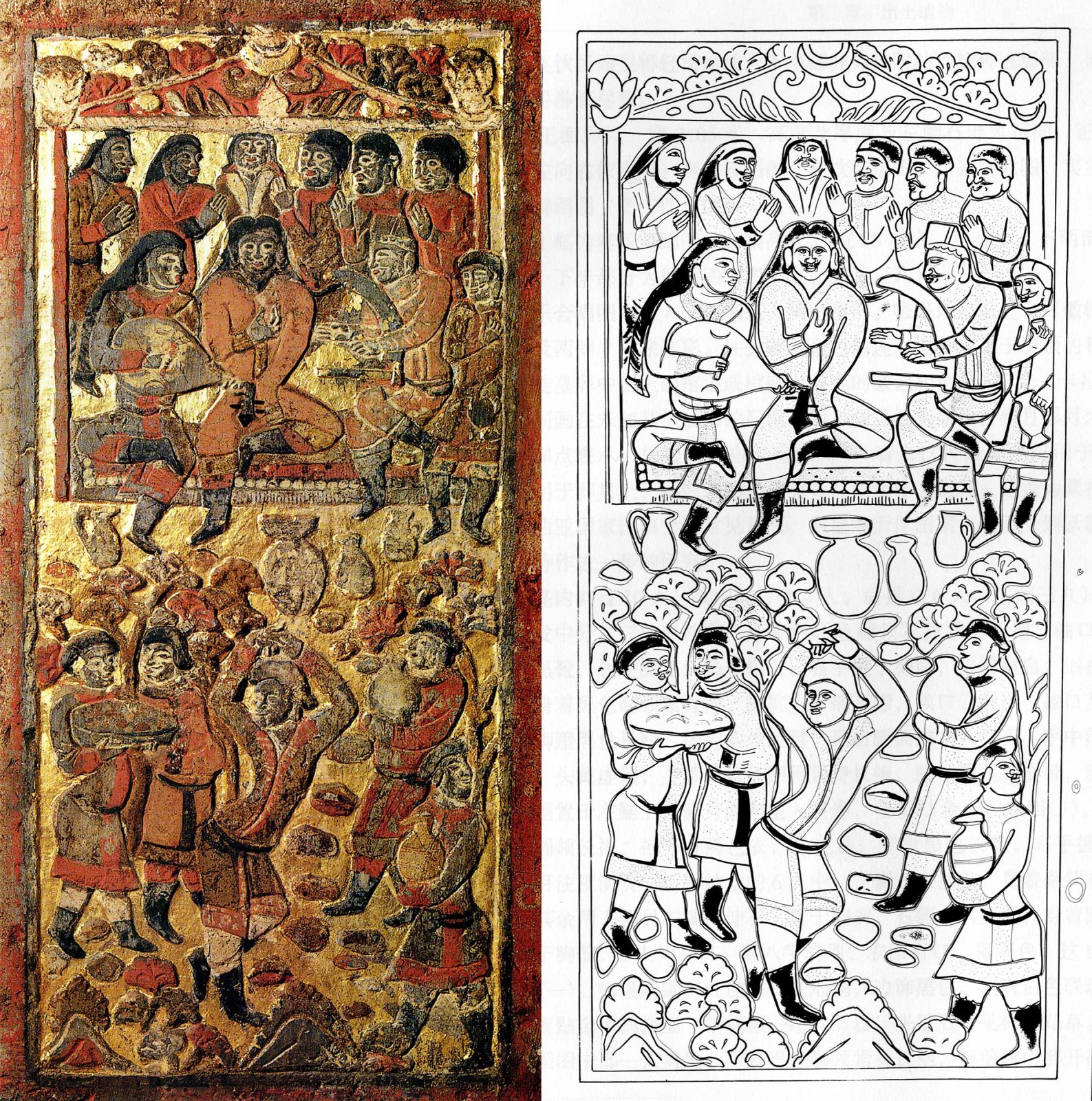

For An Qie’s bed, the screen is made up of twelve panels, which are carved in relief with lively scenes from incidents in his life; bright pigments as well as extensive gilding further enliven the scenes; Fig. 11. The pictorial reliefs on Shi Jun’s sarcophagus do not seem as flamboyant as those on An Qie’s funerary bed, but the compositions are highly detailed, and traces of paint and gilding indicate that they were originally similarly embellished.

Fig. 11 Click to enlarge and scroll through the Panels from the Funerary Bed of An Qie. Xi’an, 579 CE. Shaanxi Provincial Institute of Archaeology, Xi’an. View object page

Adapted from Shaanxi Provincial Institute of Archaeology, Xi’an Bei Zhou An Jia mu, pls. 26, 37, and 66.

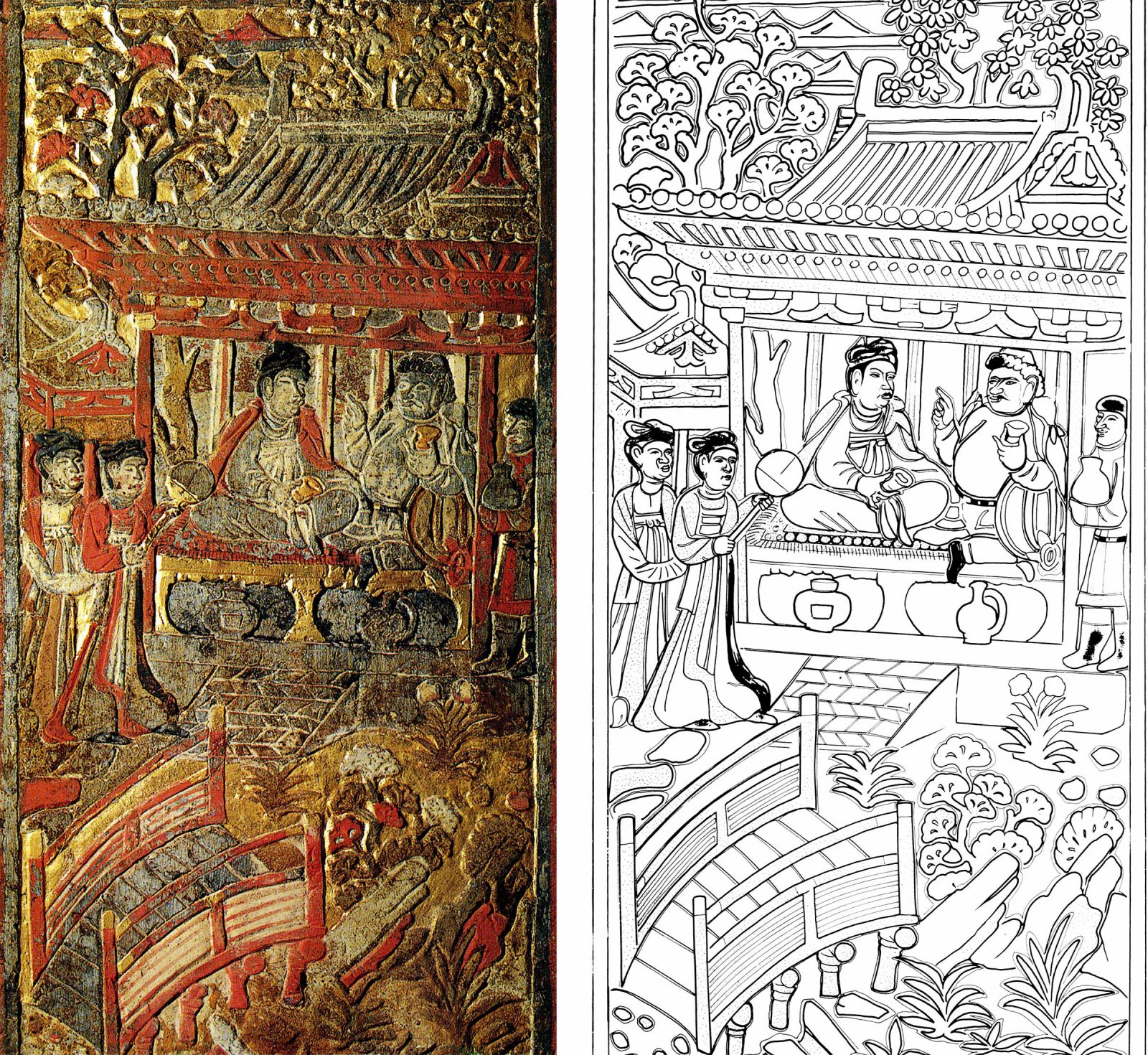

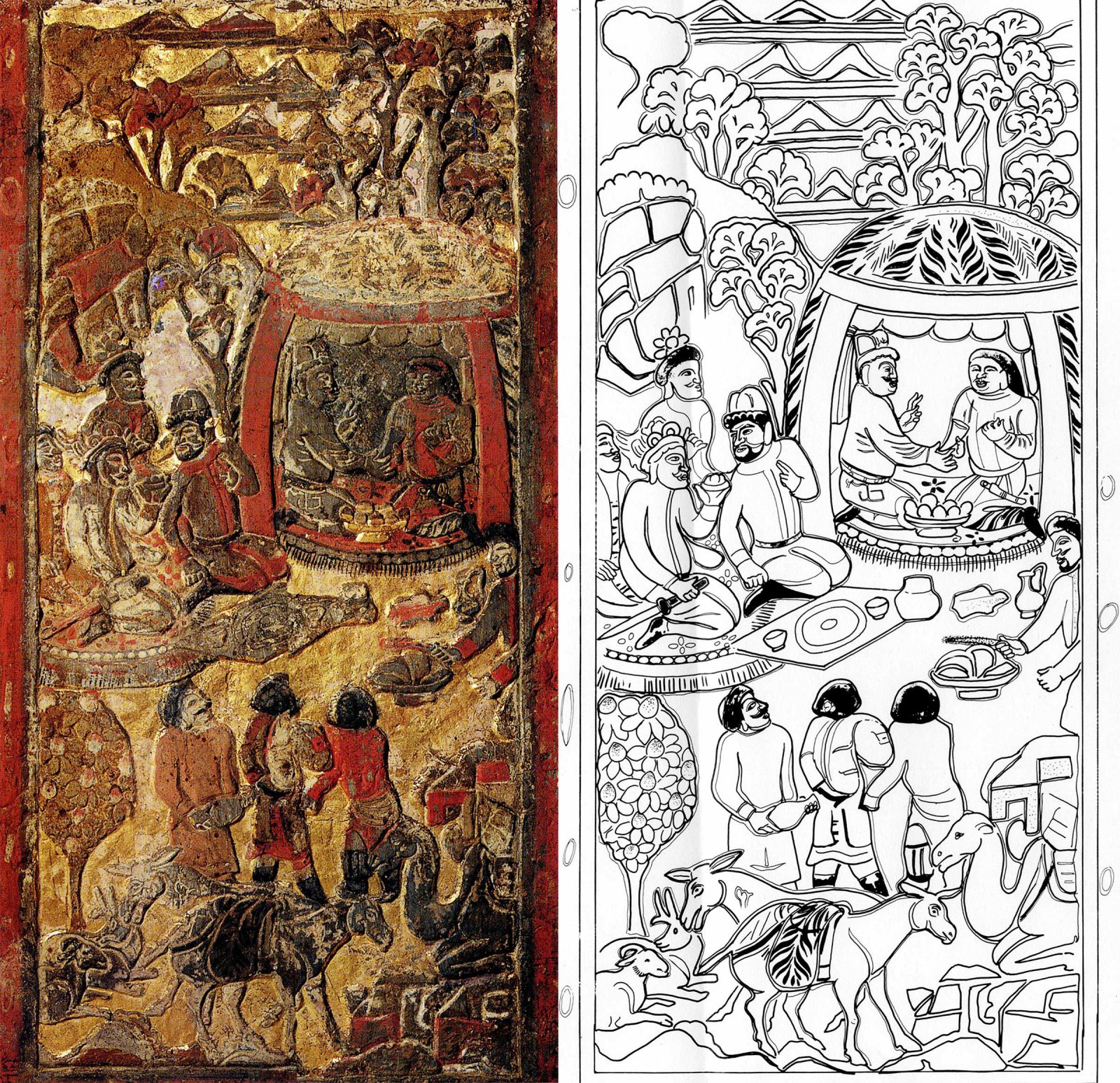

The remaining panels show other aspects of An Qie’s life, actual and idealized. In four of them we again see him acting as sabao. In one, he visits a Turkic chieftain in his tiger-skin yurt while other officials, each identified by different headgear, sit outside; Fig. 14. This scene takes place “on the road” in a mountainous landscape, as suggested by the men and pack animals (a donkey and a Bactrian camel) in the foreground. Other panels show An Qie or a Turk seated in a yurt, a grape arbor, or a garden pavilion, feasting and being entertained by musicians and a male dancer who performs the Sogdian Whirl; Fig. 15.

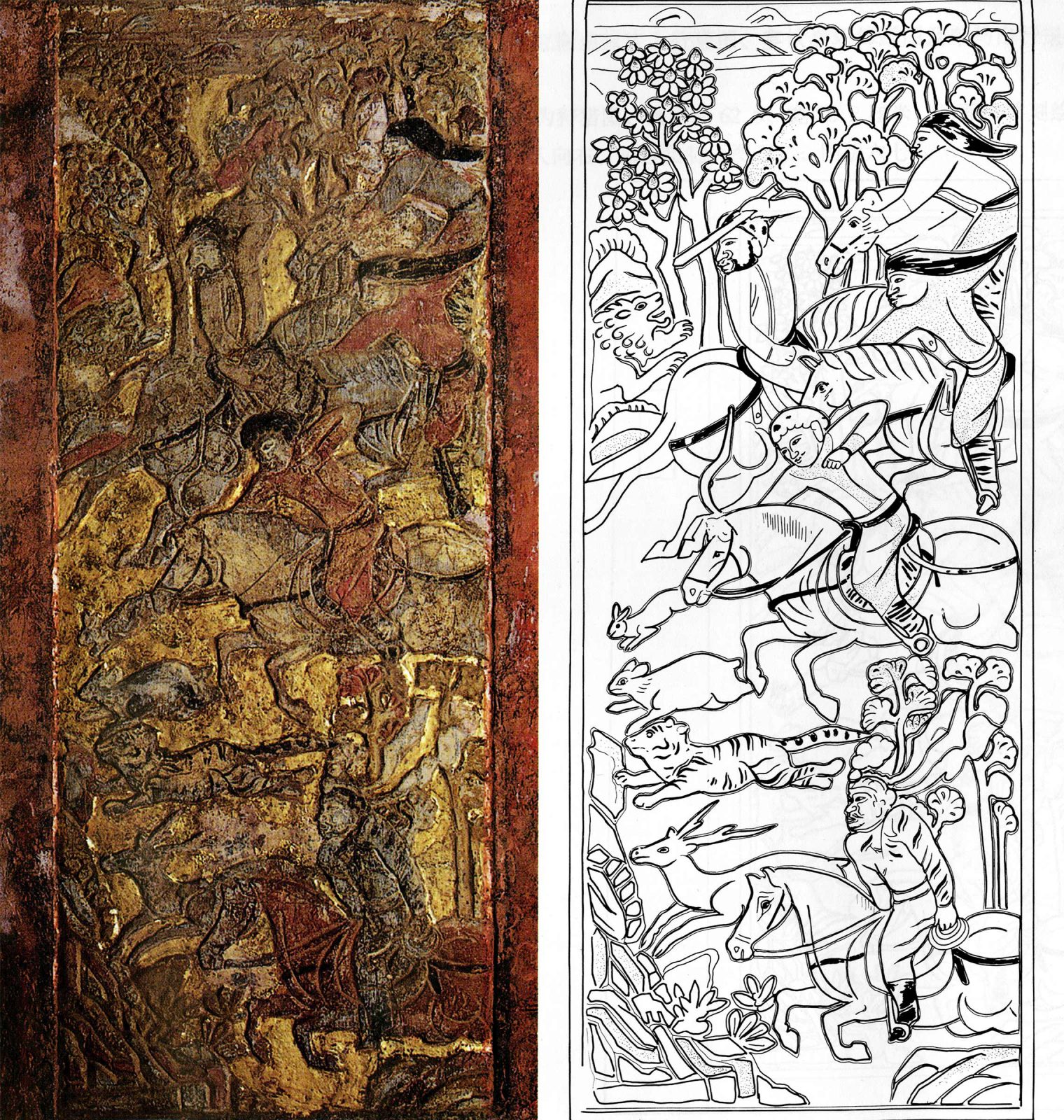

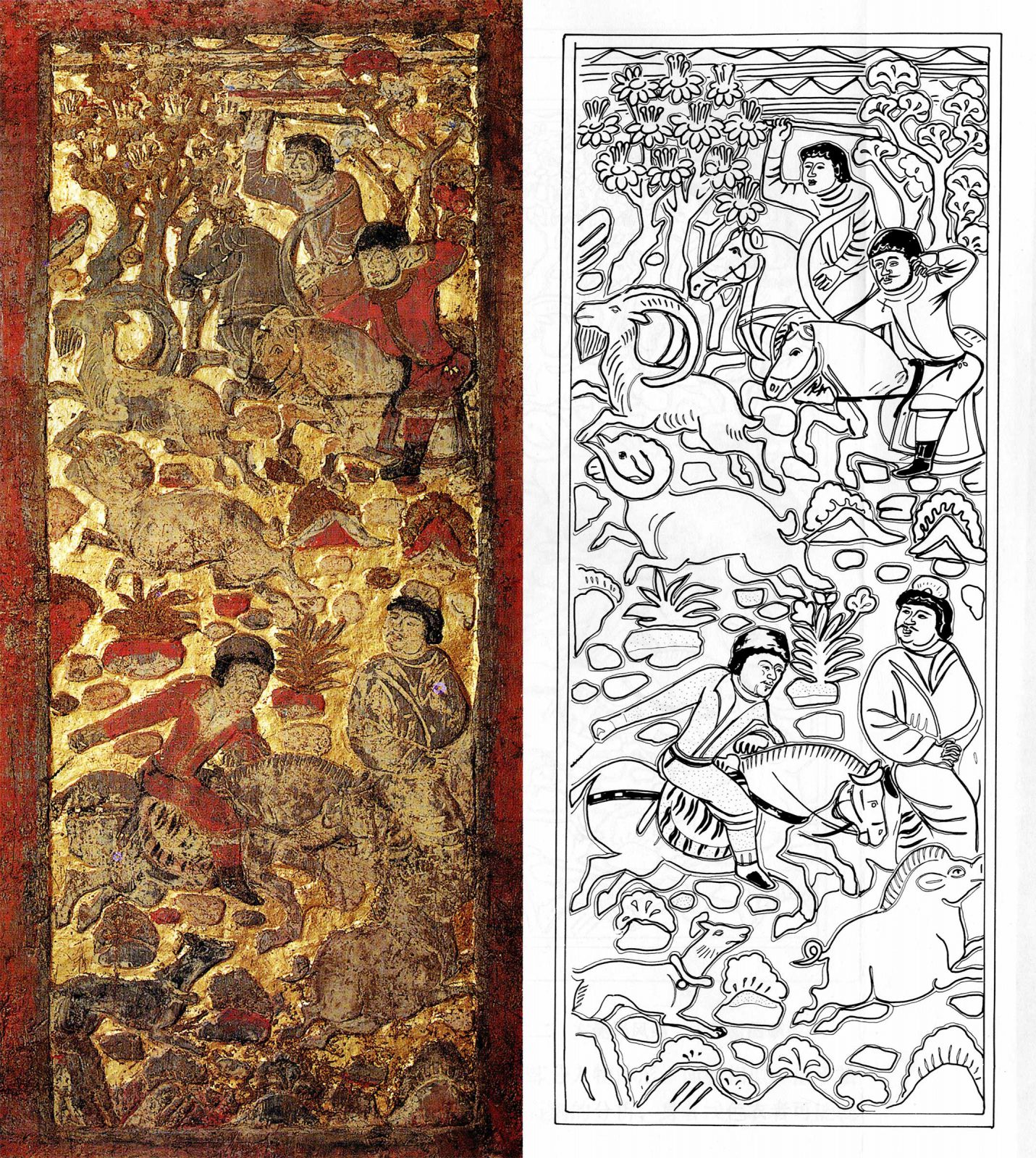

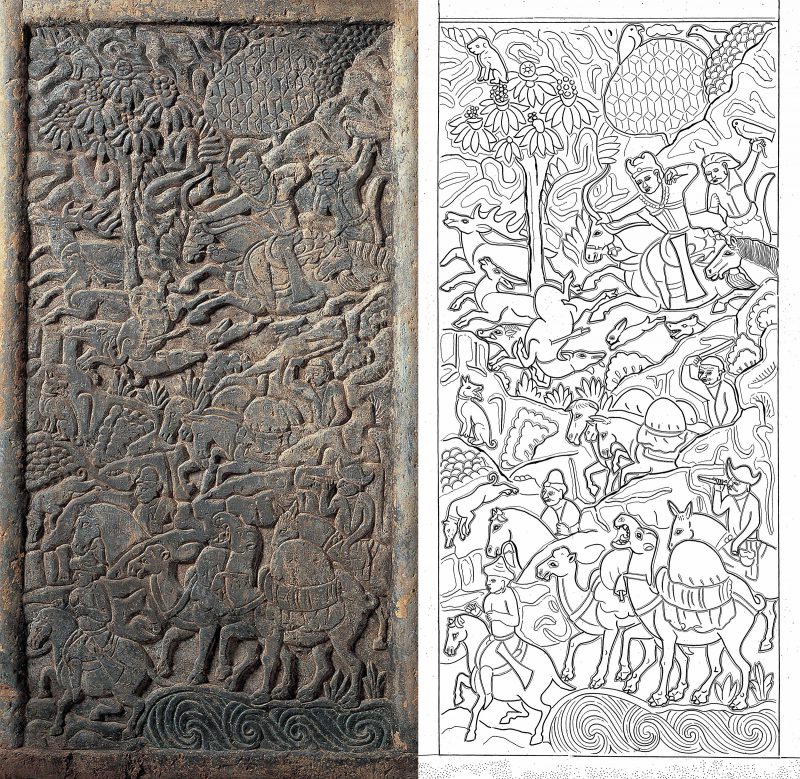

Some of these banqueting scenes are combined with those of hunting, while two panels are entirely given over to the hunt; Figs. 16 and 17.

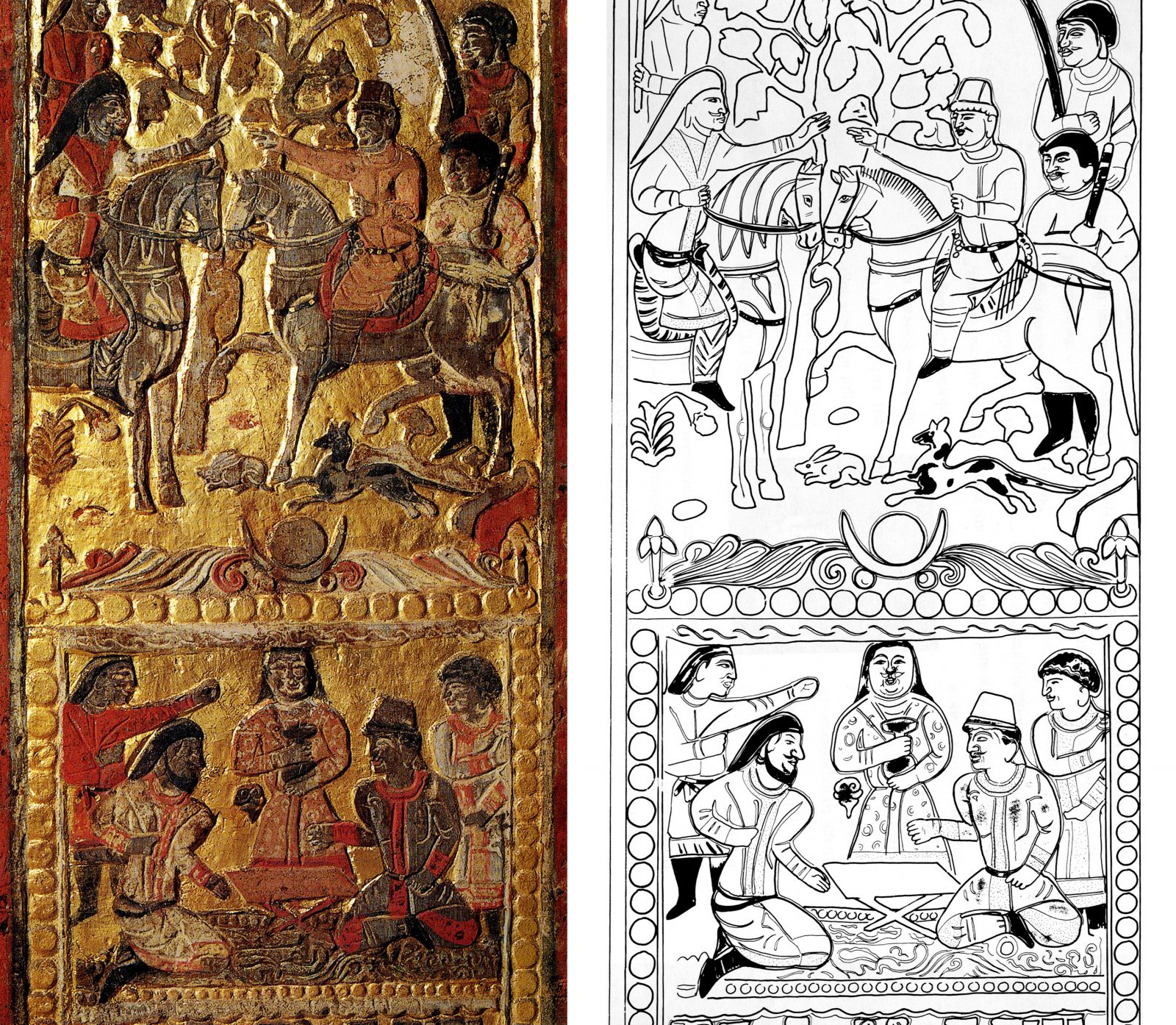

So, too, in the sarcophagus of Shi Jun, we see Shi Jun and his entourage hunting, drinking, and feasting with high-ranking personages in different settings, such as lavish pavilions, in the countryside where a yurt-shaped tent has been erected; Figs. 18–20.

Fig. 18 Detail of Sarcophagus of Shi Jun (Wirkak) and Wiyusi: Hunting Party (upper part of image) and Caravan by River; 579–80 CE. Shaanxi History Museum, China.

Image courtesy of Shaanxi Provincial Institute of Archaeology. Drawing after Xi’an Municipal Institute for the Conservation of Cultural Relics and Archaeology 西安市文物保护考古研究院, “Xi’an Bei Zhou Liangzhou sabao Shi Jun mu fajue jianbao 西安北周凉州萨保史君墓发掘简报” [Short excavation report of the Northern Zhou dynasty tomb of the Liangzhou sabao Shi Jun, Xi’an]. Wenwu 3 (2005): 4–33.

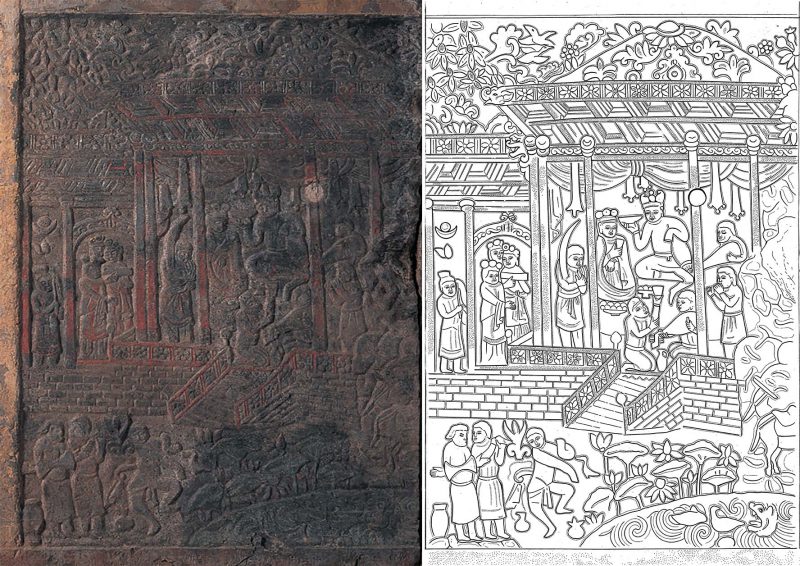

Fig. 19 Detail from Sarcophagus of Shi Jun (Wirkak) and Wiyusi: Meeting at Entrance of Yurt/Tent. Xi’an, 579–80 CE. Shaanxi History Museum, China.

Image courtesy of Shaanxi Provincial Institute of Archaeology. Drawing after Xi’an Municipal Institute for the Conservation of Cultural Relics and Archaeology, “Xi’an Bei Zhou Liangzhou sabao Shi Jun mu fajue jianbao,” Wenwu 3 (2005): 4–33.

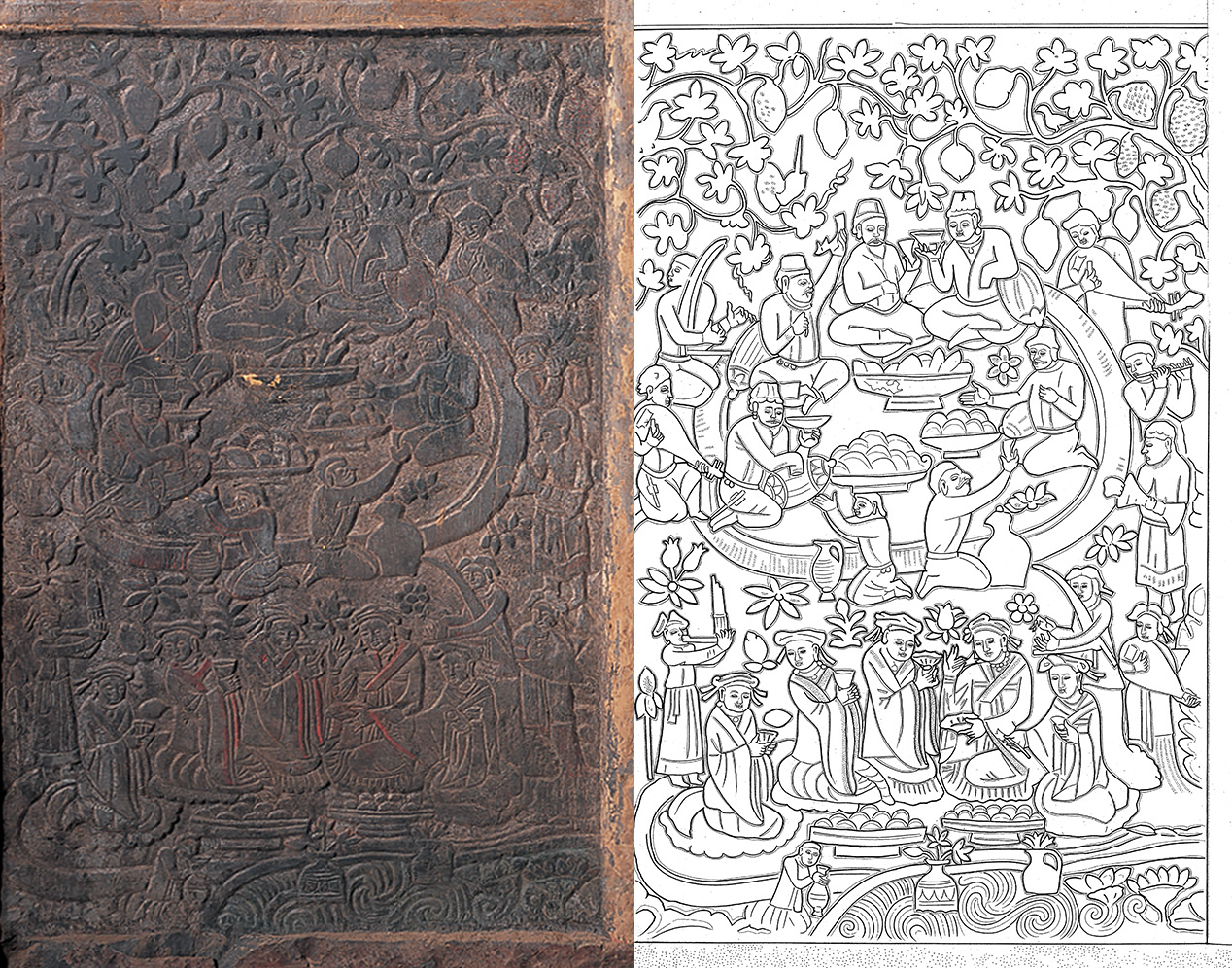

Fig. 20 Detail from the Sarcophagus of Shi Jun (Wirkak) and Wiyusi: Couple in a Pavilion Enjoying Entertainments. Xi’an, 579–80 CE. Shaanxi History Museum, China.

Image courtesy of Shaanxi Provincial Institute of Archaeology. Drawing after Xi’an Municipal Institute for the Conservation of Cultural Relics and Archaeology, “Xi’an Bei Zhou Liangzhou sabao Shi Jun mu fajue jianbao,” vol. 3: 4–33.

In one bucolic scene, Shi Jun enjoys food and wine in a grape arbor; Fig. 21. The party is being entertained by musicians and attended to by several servants. Shi Jun is most likely one of the two figures in the center, and the person to his left holds up a rhyton to toast them. This quintessentially Iranian hornlike drinking vessel typically ends in an animal-shaped spout; Fig. 22.

Both feasting and hunting were used in Iranian art to symbolize the “good life” of the aristocrat. (In neighboring Sasanian Persia, the hunt symbolized the power of the king.) Even though An Qie, Shi Jun, and other Sogdian elites clearly indulged in banquets, accompanied by music and dance, it is doubtful whether they actually hunted—certainly not lions. These are not native to China, as we can see by the fanciful treatment of the lion’s mane and shoulder in the lower half of a panel from An Qie’s bed; Fig. 23.

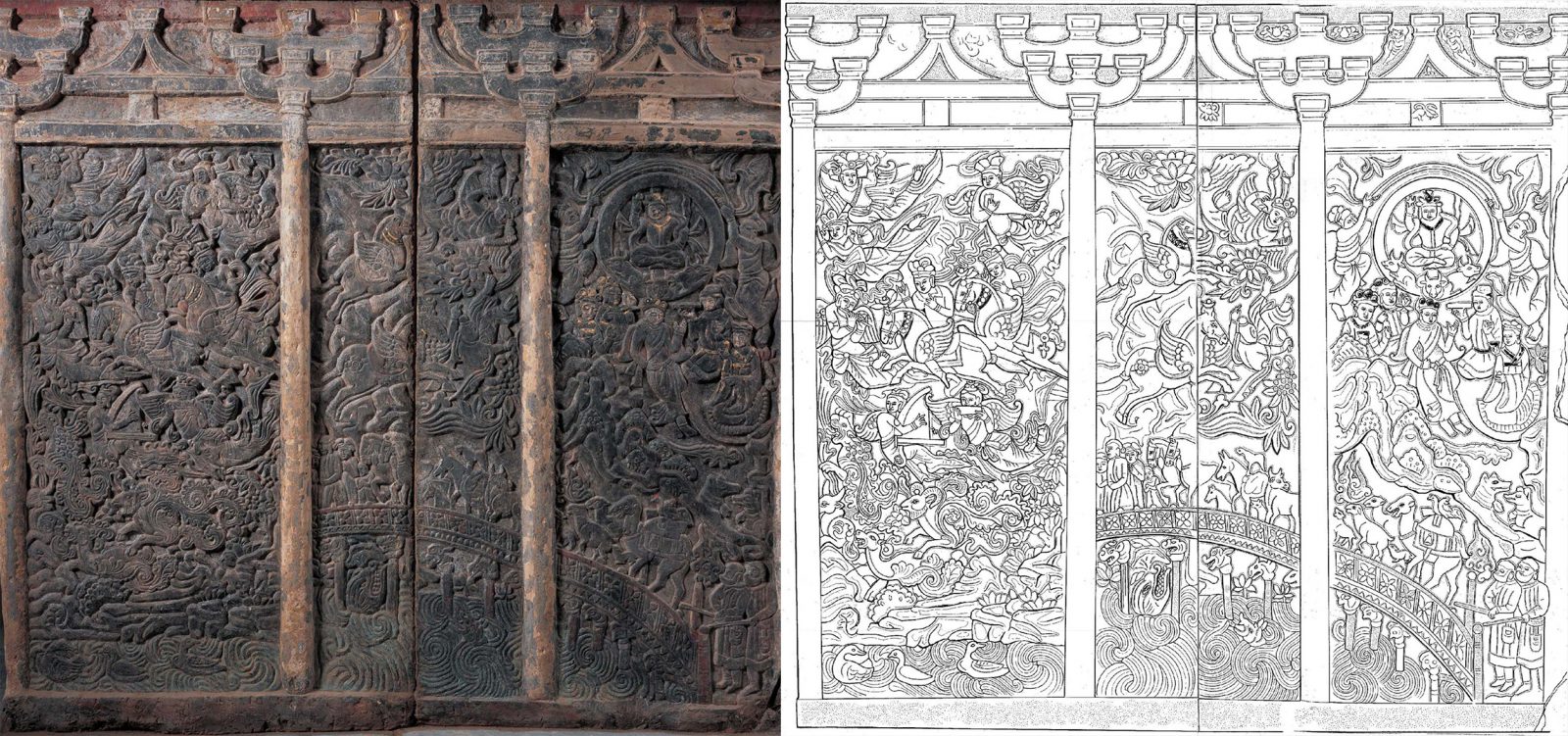

Alongside the worldly pursuits of work and leisure, the tombs also testify to elite Sogdians’ religious beliefs. Shi Jun is depicted not only as a successful merchant and sabao, but also as a follower of Zoroastrian/Mazdean doctrine, and we see dimensions of his religious practice depicted in various places. Adjoining the doorway to the houselike sarcophagus stand four-armed, fierce-looking guardians; Figs. 24 and 25. Each is flanked by a single panel carved with a birdman, the lower part of its face covered by a padam, as he tends the sacred fire. Above each birdman is part of a Central Asian orchestra, no doubt alluding to the Zoroastrian paradise, filled with music and song.

Elsewhere on his sarcophagus, Shi Jun shows himself, his wife, and their three sons as pious Zoroastrians, but no scene quite matches the level of detail and drama of the final three panels, located on the eastern wall of the sarcophagus; Fig. 26. Together these three panels illustrate Shi Jun and Wiyusi being judged and making their journey to heaven, where they are welcomed by the gods.

Fig. 26 East wall of Sarcophagus of Shi Jun (Wirkak) and Wiyusi: Shi Jun and His Wife Cross the Chinvat Bridge To Be Received into Paradise ;. Excavated in Xi’an, Shaanxi Province, China; dated to 579–80 CE.

Image courtesy of Shaanxi Provincial Institute of Archaeology. Drawing after Xi’an Municipal Institute for the Conservation of Cultural Relics and Archaeology 西安市文物保护考古研究院, “Xi’an Bei Zhou Liangzhou sabao Shi Jun mu fajue jianbao 西安北周凉州萨保史君墓发掘简报” [Short excavation report of the Northern Zhou dynasty tomb of the Liangzhou sabao Shi Jun, Xi’an]. Wenwu 3 (2005): 4–33.

Fig. 27 Detail of east wall of Sarcophagus of Shi Jun (Wirkak) and Wiyusi: The Wind God Weshparkar. Excavated in Xi’an, Shaanxi Province, China, dated to 579–80 CE. Stone relief with traces of pigment and gilding; H. 1.58 × L. 2.45 × D. 1.55 m. Shaanxi History Museum, China.

Image courtesy of Shaanxi Provincial Institute of Archaeology. Drawing after Xi’an Municipal Institute for the Conservation of Cultural Relics and Archaeology, “Xi’an Bei Zhou Liangzhou Sabao Shi Jun mu fajue jianbao,” fig. 27.

Fig. 28 God Shiva with Goddess Parvati [together called Uma-Maheshvara], Seated on the Bull Nandi. Clay, gypsum. Temple II, Panjikent, Tajikistan. Early 8th century CE.

After National Museum of Antiquities of Tajikistan: The Album, ed. R. Masov, S. Bobomulloev, M. Bubnova (Dushanbe, National Museum of Antiquities: 2005), 170, pl. 2.

At the top of the rightmost section is an enthroned deity, surveying the scene—most likely Weshparkar, the ancient Iranian/Sogdian god of celestial space; Fig. 27. Due to the lack of other available models, the Chang’an stone carver has based Weshparkar on the form of the Hindu deity Shiva Maheshvara; Fig. 28. Below him is the crowned dēn, a beautiful maiden with two attendants welcoming Shi Jun and his wife, who sit opposite them with drinking vessels in their hands. At the lower right of the panel, two priests wearing padams stand at the entrance to the Chinvat Bridge, which spans perilous waters filled with demonic creatures. The couple move across the bridge toward paradise, followed by horses, a donkey, and other livestock, which includes laden camels—a reminder of the source of Shi Jun’s mercantile wealth. The dense composition of the next panel shows the couple, surrounded by heavenly musicians, rising to heaven on winged horses. This scene is unique so far among the tomb carvings of Sogdians living in China, and reflects knowledge of Zoroastrian texts and religious beliefs. The culmination of Shi Jun’s and Wiyusi’s journey is their feasting in paradise with Weshparkar.

Taken together, these tombs offer us vivid glimpses of individual Sogdians’ lives and aspirations, allowing us to move past the generalized descriptions of the anonymous Sogdian traders and artisans we find in many descriptions of the historic Silk Road. Their tombs tell us how they (or their families) wished to tell the stories of their lives: what they did of value, what they loved, what was important to them. Moving away from the grand sweep of transcontinental trade and cultural exchange, the tombs offer a human scale at which to understand the way that China could shape the lives of individual Sogdians, and conversely, the role that individual Sogdians could play in Chinese political, social, and cultural life.

Victor H. Mair, ed., trans. The Shorter Columbia Anthology of Traditional Chinese Literature (New York: Columbia Univ. Press, 2001), 149–50.

Steven Pinker most recently put forward this argument in Steven Pinker, The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined (New York: Penguin Books, 2011). The exact numbers of the An Lushan casualties, however, are highly disputed.

The Jiu Tangshu 舊唐書 [Book of the Old Tang] (Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju, 1975), 221b: 6,243–44, quoted in Valerie Hansen, “The Astonishing Finds from the Turfan Oasis,” in Li Jian, ed., The Glory of the Silk Road: Art From Ancient China (Dayton, OH: Dayton Art Institute 2003), 36.

Cui Feng崔峰. “Sute wenhua dui Beiqi Fojiao yishu de yingxiang 粟特文化对北齐佛教艺术的影响 [The impact of Sogdian culture and the Northern Qi dynasty Buddhist art].” Gansu Gaoshi Xuebao甘肃高师学报 [Journal of Gansu Normal Colleges] 13, no. 6 (2008): 124–28; William R. B. Acker, Some T’ang and Pre-Tang Texts on Chinese Painting, translated and annotated, Sinica Leidensia, vol. 8 (London: Phaidon Press, 1979), 165.

In some writings, “An Qie” appears as “An Jia.” The transcription of the second syllable as “Jia” (still 伽) is a form that postdates the Six Dynasties period and thus is anachronistic. “Qie” more accurately transcribes this syllable’s pronunciation during the sixth century in which An Qie lived. We are grateful to Victor H. Mair (University of Pennsylvania) for explaining this discrepancy.

An Qie’s personal background is taken from Jui-Man Wu’s translation of his epitaph. See Jui-Man (Mandy) Wu, Mortuary Art in the Northern Zhou China (557–581 CE): Visualization of Class, Role, and Cultural Identity, PhD diss. (Univ. of Pittsburgh, 2010), 214–17.

For Shi Jun’s biography, see Sun Fuxi, “Investigations on the Chinese Version of the Sino-Sogdian Bilingual Inscription of the Tomb of Lord Shi,” in Étienne de la Vaissière and Éric Trombert, eds., Les Sogdiens en Chine, Études Thématiques 17 (Paris: École française d’Extrême-Orient, 2005), 47–56.

Luo Feng, “Sabao: Further Considerations of the Only Post for Foreigners in the Tang Dynasty Bureaucracy,” China Archaeology and Art Digest 4, no. 1 (Dec. 2000): 179.

Albert E. Dien, “Observations Concerning the Tomb of Master Shi,” Bulletin of the Asia Institute, n.s. 17 (2003): 109.

Although An Qie’s bed was not canopied, stone beds found in other tombs have metal loops near their corners to support the poles to which cloth canopies were attached.

Yang Junkai, “Carvings on the Stone Outer Coffin of Lord Shi of the Northern Zhou,” in Étienne de la Vaissière and Éric Trombert, eds., Les Sogdiens en Chine, Études Thématiques 17 (Paris: École française d’Extrême-Orient, 2005), 21–46.

Yang Junkai, “Carvings on the Stone Outer Coffin of Lord Shi of the Northern Zhou,” in Étienne de la Vaissière and Éric Trombert, eds., Les Sogdiens en Chine, Études Thématiques 17 (Paris: École française d’Extrême-Orient, 2005), 37. See also Frantz Grenet, “More Zoroastrian Scenes of the Wirkak (Shi Jun) Sarcophagus,” Bulletin of the Asia Institute, n.s. 27 (2013 [2017]): 1–12, esp. 5.