Charred Wood Caryatid

Caryatid Figure

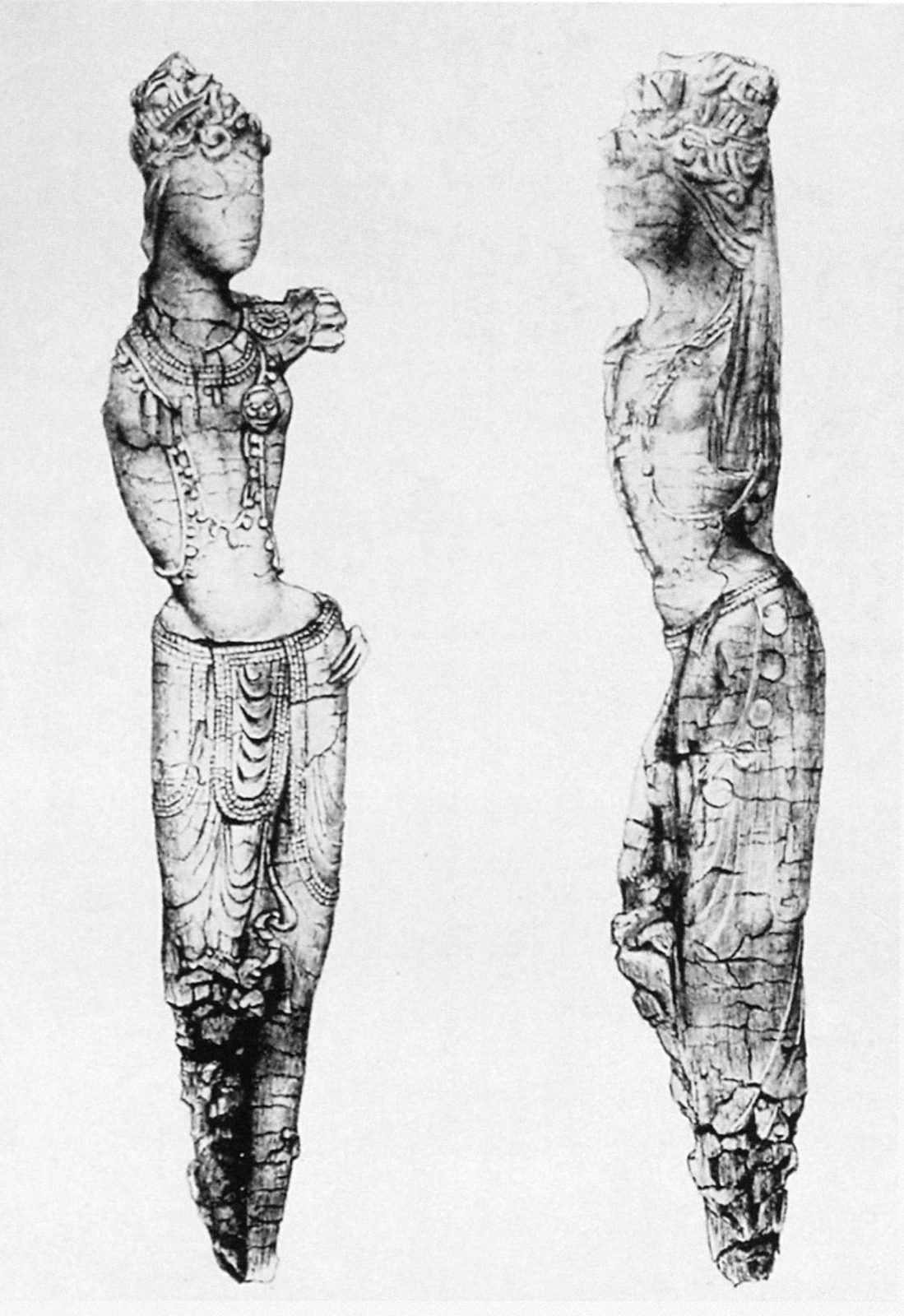

Panjikent, Tajikistan (in ancient Sogdiana) , Site III:47, first half of 8th century CE. Charred wood; H. 115 × W. 21.5 cm

The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, SA-15911

Photograph © The State Hermitage Museum

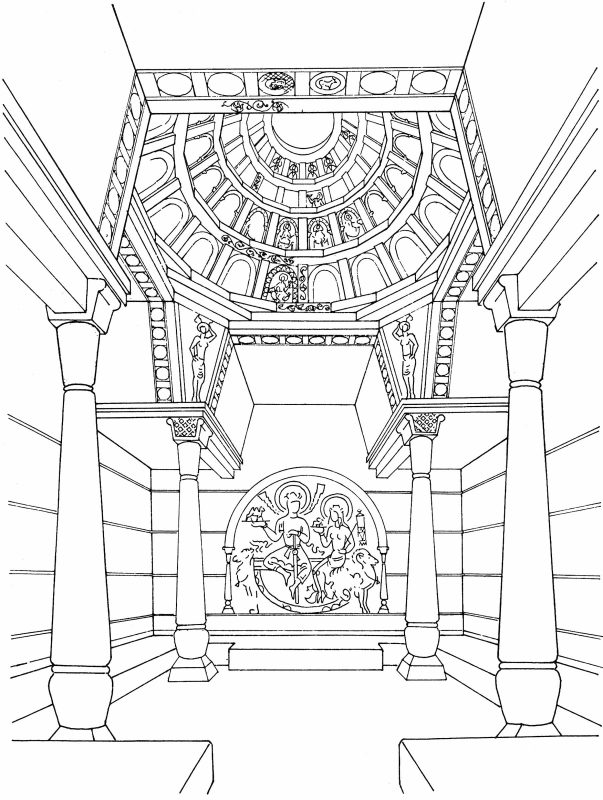

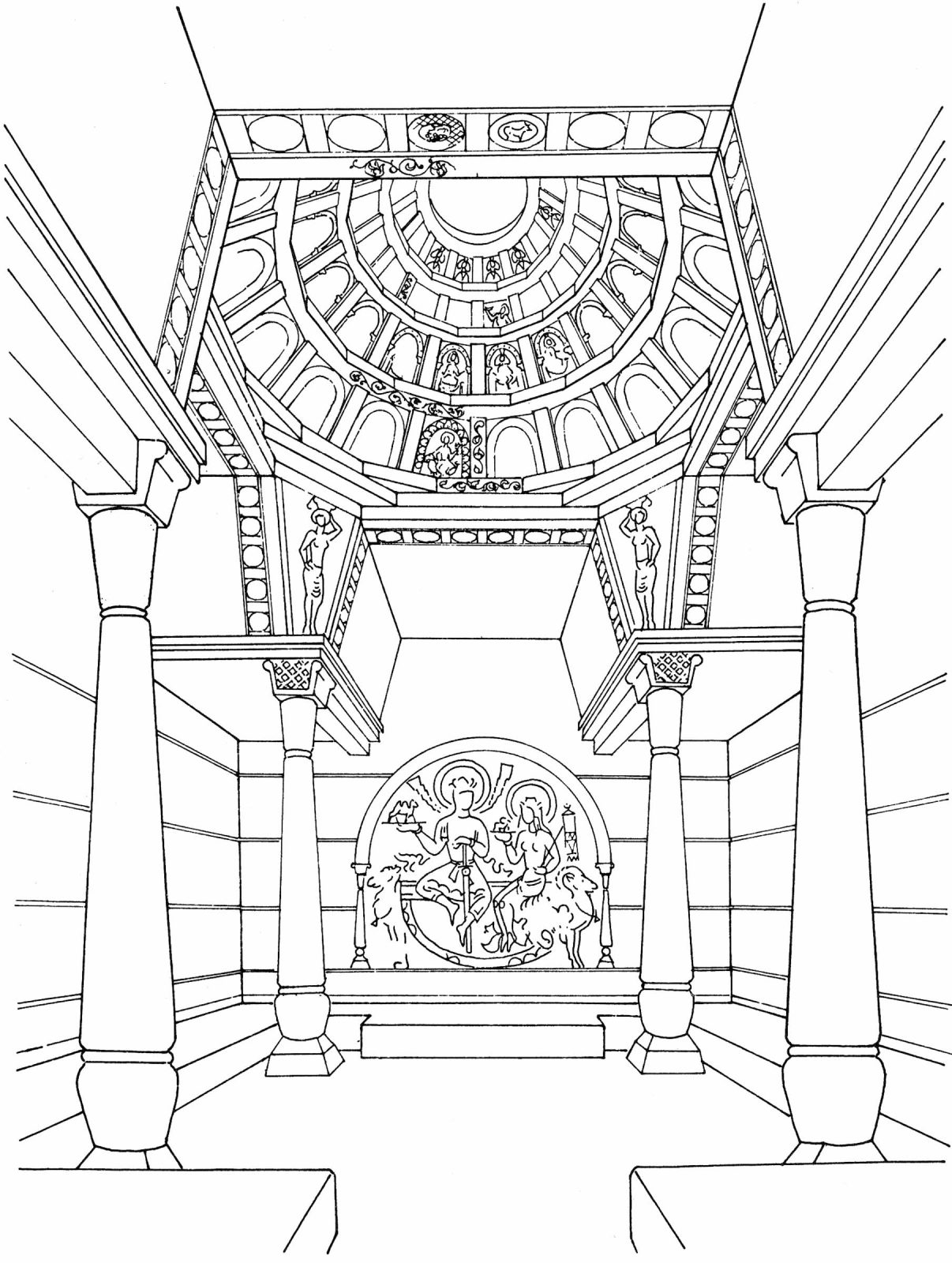

Such lithe half-figures served to decorate the reception halls of grand houses at the archaeological site of Panjikent,The City of Panjikent and Sogdian Town-Planning Learn more about Panjikent and Sogdian town-planning in present-day Tajikistan. Unlike true caryatids, these figures were not actual architectural supports but decorative embellishments for the transitional zone between the square hall and the domed ceiling above it; Fig. 1.

He and other caryatids stand in the classical Indian tribhanga stance, with body bent at neck, waist, and knee to form a gentle S-curve; Fig. 2. Because viewers would see them from below, the artisans purposely elongated the caryatids to counteract foreshortening of their bodies.

The domed ceilings over such houses, above the zone with caryatids, would be inset with wooden plaques carved in a variety of figural, vegetal, and geometric designs. Three figural examples here show a battle between a hero and a winged lion, Fig. 3; a deity holding a peacock, Fig. 4; and the goddess Nana on her lion, Fig. 5.

Normally, such pieces would not survive intact to this day, but the fire that destroyed half of Panjikent during the Arab siege of 722 buried this and other wooden sculptures under collapsed walls and ceilings. This, ironically, protected them by sealing them off from the elements. Their subsequent excavation and conservation highlight the remarkable expertise of Panjikent’s archaeologists and restorers.

by Julie Bellemare and Judith A. Lerner

See Pavel Lurje, “Depictions, Imprints, Charcoal and Timber Finds: Few Notes on Wooden Architectural Elements in Sogdiana,” in The Ruins of Kocho: Traces of Wooden Architecture on the Ancient Silk Road, eds. Lilla Russell-Smith and Ines Konczak-Nagel (Berlin: Museum für Asiatische Kunst, 2016), 17–26.

Larisa Kulakova, “128: Lion in a Roundel,” in Expedition Silk Road—Journey to the West: Treasures from the Hermitage, ed. Pavel Lurje and Kira Samoslyuk (Amsterdam: De Nieuwe Kerk, 2014), 198.