The Wall Paintings in the Palace at Varakhsha

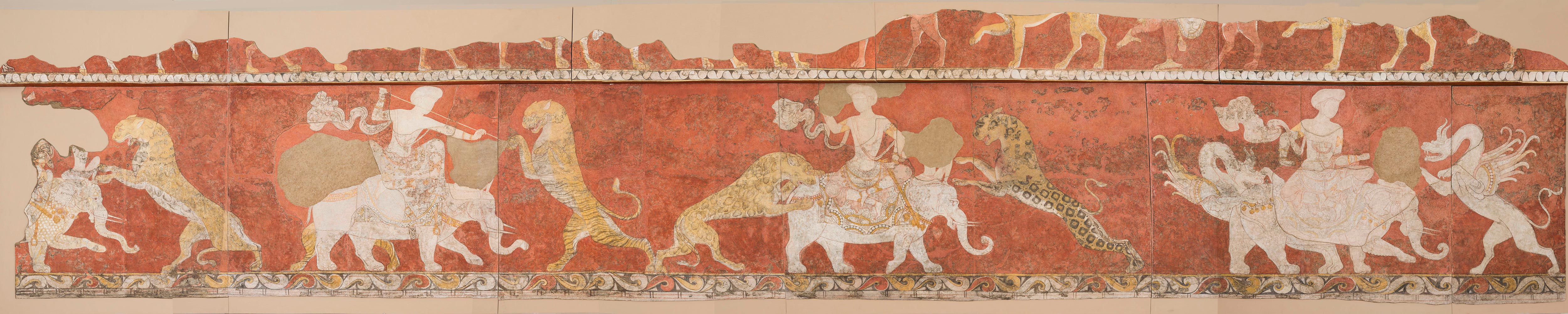

Battle between a Deity and Beasts of Prey

Red Hall, Palace at Varakhsha, Uzbekistan (in ancient Sogdiana) , late 7th–early 8th century CE

Wall painting; H. 163 × W. 902 cm

State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, SA-14658-14675

Photograph © The State Hermitage Museum.

The town of Varakhsha, located on the northwestern periphery of the Bukhara oasis , was the first Sogdian archaeological site that Europeans noted in the 19th century. It was not until 1937, however, that Vasiliy A. Shishkin began excavations of the palace there. Interrupted by World War II, Shishkin resumed his work in 1947 and continued until 1955. The Museum of Oriental Art, Moscow, later carried out excavations in 1986 and 1991.

Set within the citadel above the town, the palace contained a large, open courtyard, and was distinguished by three sizable, vaulted halls (iwans) and several other spacious, painted rooms. The remains of the East Hall bear traces of a monumental painting of a figure seated on a throne supported by winged camels, all against a deep blue ground. In the left-hand portion of this painting are the remnants of drawings of several figures kneeling at an elaborate, free-standing altar, with the first one tending its flame. Better preserved is the Red Hall, so named because of the vivid background color, on which a number of animal-and-human combat groups are arranged in a long, horizontal frieze. We see pairs of leopards; panthers; tigers; and horned, dragonlike creatures with elaborately feathered wings attacking a series of elephant riders and their mahouts. It is possible, though, that we may be watching a sequential unfolding in time of an epic battle in which a sole elephant rider is the hero; Fig. 1.

Fig. 1 Click to enlarge and scroll through the Battle between a Deity and Beasts of Prey. Red Hall, Palace at Varakhsha, Uzbekistan (in ancient Sogdiana), late 7th–early 8th century CE. Wall painting; H. 163 × W. 902 cm. The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, SA-14658-14675.

Photograph © The State Hermitage Museum.

Above this frieze is another, a procession of animals of which only the lower portion survives. Such organization into horizontal registers is similar to that of the wall paintings excavated at Panjikent in the Samarkand oasis, but the subject matter of the main register is unique in the arts of Central Asia. Dressed in loose-fitting dhoti pants, flowing scarf, and turban, the bare-chested elephant rider suggests the chief Vedic or Hindu deity Indra (also a Buddhist guardian deity), whose vehicle is the elephant. Given the syncretic nature of Sogdian religion, it is also quite possible that he is Adhvagh, the Sogdian version of the supreme Zoroastrian god Ahura Mazda. As for the rider’s elephant, it is clear that the artists had never seen a real one. It is clumsily depicted, with a disproportionately small head and short legs. Further evidence of the artist’s unfamiliarity with the animal is that its tusks are shown growing from its lower jaw.

Such inaccuracies did not matter, however, to the person who painstakingly cut separate images from the painting before demolition of the hall’s roof in the mid-8th century. From his careful examination of the Red Hall during its reexcavation in 1987, numismatist/archaeologist Aleksandr Naymark suggested that those images served as artists’ models, thereby passing on Sogdian artistic tradition; Fig. 2.

by Julie Bellemare and Judith A. Lerner

In his highly informative essay “Returning to Varakhsha,” Aleksandr Naymark credits the British artist and adventurer James Baillie Fraser with mentioning the first Sogdian archaeological site in European literature. See Aleksandr Naymark [Naimark], “Returning to Varakhsha,” Silk Road Foundation Newsletter 1, no. 2 (December 2003): 18. See http://www.silkroadfoundation.org/newsletter/december/varakhsha.htm.

Vasilii Afanas’evich Shishkin Василий Афанас’евич Шишкин, Varakhsha Варахша, in Russian (Moscow: USSR Academy of Science Publishing, 1963).

For an interpretation of the palace’s architecture and reconstructions of both the Blue and Red Halls, see Boris I. Marshak [Marschak/Maršak], “The Ceilings of the Varakhsha Palace,” Parthica 2 (2000): 153–67. For a reconstruction of the Red Hall in cross-section, see 165, fig. 13.

For a fuller discussion of the rider’s identification and the difficulties of recognizing Ahura Mazda in Sogdian visual culture, see Michael Shenkar, Intangible Spirits and Graven Images: The Iconography of Deities in the Pre-Islamic Iranian World. Series, Magical and Religious Literature of Late Antiquity, vol. 4 (Leiden and Boston: Brill 1974), 63–65. Shishkin had posited that the painting represented the struggle of Good (the hero) against Evil (the felines and dragon), a concept underlying Mazdean beliefs.

“These cuts seem to be the result of very accurate and time-consuming work aimed at the removal of wall fragments with an intact painted surface. Since each cut concentrated on a certain compact element of images, like the head of a man or the wing of a griffin, these cuts are very likely to be done by an artist who used this opportunity to obtain samples of superior work for his pattern collection from the paintings destined for inevitable destruction. This unusual fact provides us with a rare insight into one of the mechanisms that allowed the elements of pre-Islamic artistic tradition to be passed to the art of the early Islamic period.” Alexandr Naymark [Naimark], “Returning to Varakhsha,” Silk Road Foundation Newsletter 1, no. 2 (December 2003): 32.