Painting of Chinese monk Xuanzang 玄奘, also called Tang Seng 唐僧, on his quest to India to obtain Buddhist sutras. Born in 602 CE in Luoyang 落陽市, Henan Province 河南省, China, he died in 664 CE in Chang’an 長安市, now Xi’an 西安市, in Shaanxi Province 陝西省.

Image “Xuanzang w” by Alexcn is released to public domain.

Xuanzang

by Matthew Z. Dischner

A prolific writer and well-traveled Buddhist monk, Xuanzang is remembered today for his account of a sixteen-year pilgrimage to India, and his subsequent career as translator of Buddhist scriptures. His writings are extremely valuable, since they are among the few primary sources on the Sogdians that have survived.

Born into a scholarly family, Xuanzang at first received a strict Confucian education. At the age of thirteen, however, he followed in the footsteps of an older brother who was a Buddhist monk and entered a Buddhist monastery. By twenty, he had become a fully ordained monk. Xuanzang then spent the next several years in Chang’an (now called Xi’an 西安) , the capital of the Tang dynasty, where he studied Sanskrit alongside other foreign languages.

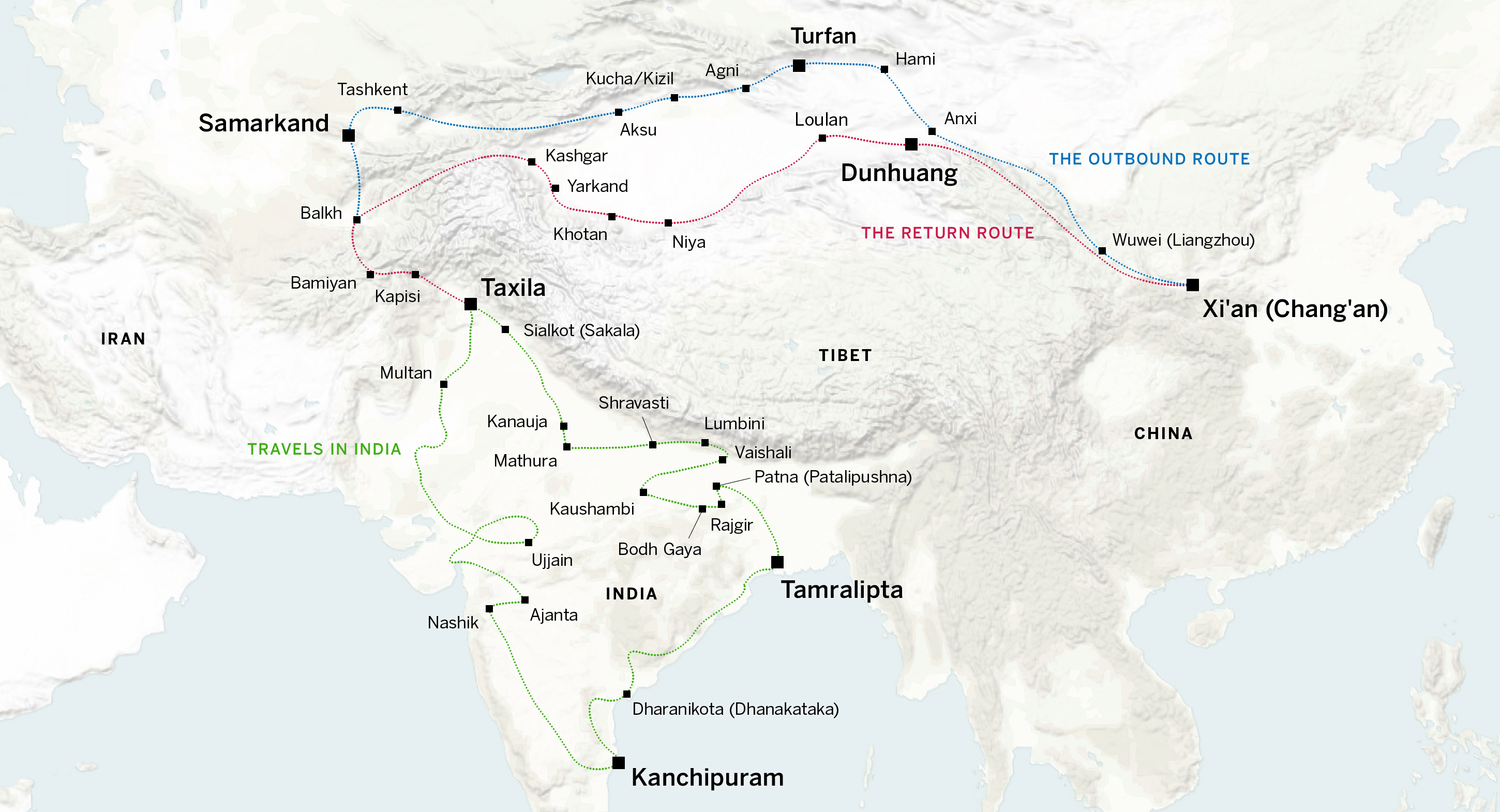

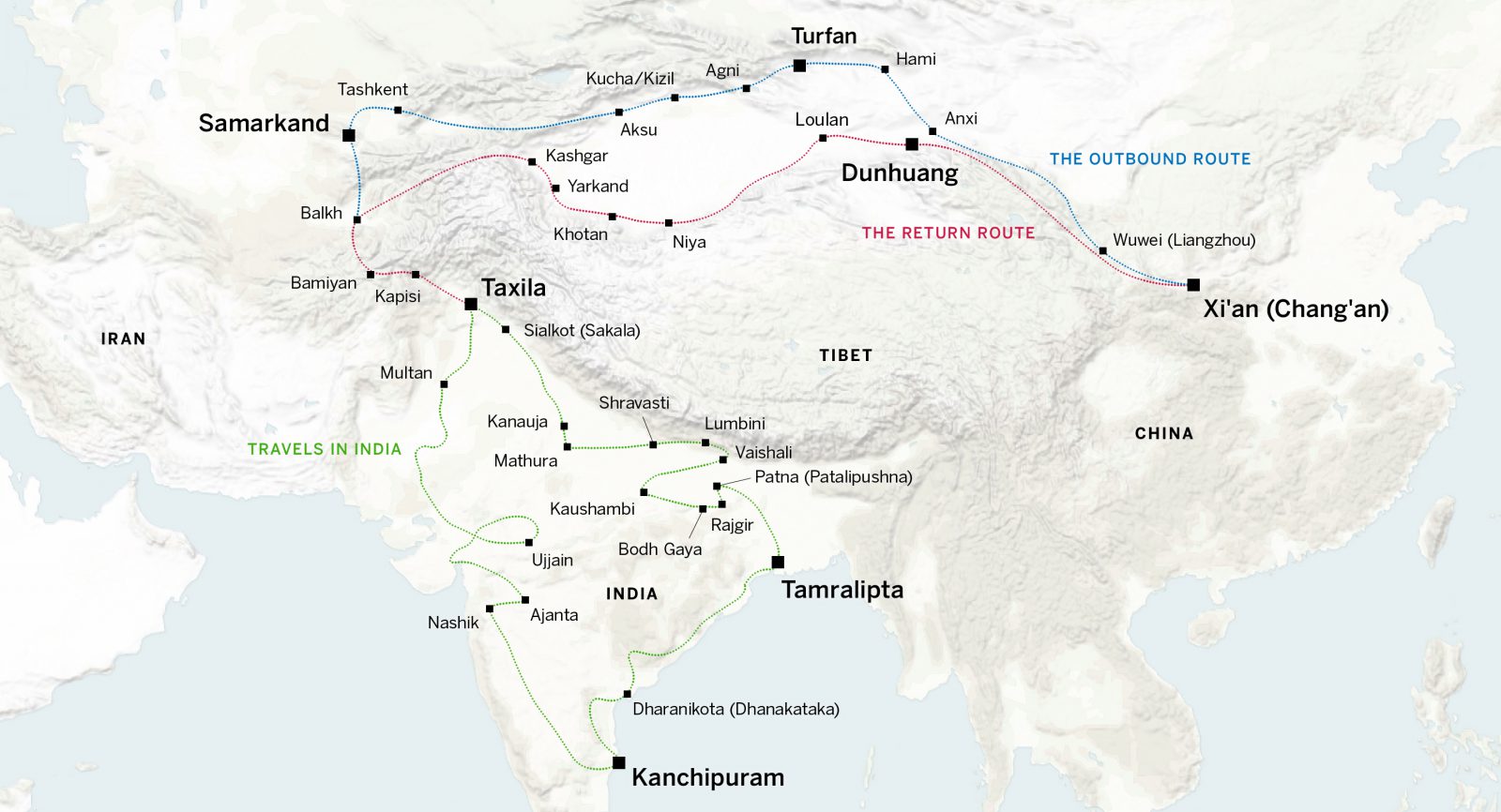

Confused by discrepancies he found in the Buddhist texts, Xuanzang resolved to embark on a pilgrimage to India. There he planned to study in the birthplace of Buddhism and reconcile the contradictions in the texts he had studied in China. Due to ongoing conflict with Turkic peoples of the steppe, however, the Chinese emperor Tang Taizong 唐太宗 (598–649; r. 626–649) had banned foreign travel on the grounds of security. Xuanzang nevertheless resolved to go, inspired by a vision. Ignoring any legal repercussions, in 629 CE he slipped across the border and headed for India. He would not return for fourteen years; Fig. 1.

Traveling by night and without a guide, Xuanzang arrived in Liangzhou 涼州 (modern-day Wuwei 武威市, in Gansu Province 甘肅省) at the western frontier of China. It was the terminus of the route to and from Central Asia as it skirts the southern edge of the Taklamakan Desert . There he spent a month preaching, before being invited by the king of Turfan , a devout Buddhist. Realizing that the king planned to detain him for life to be the ecclesiastical head of his court, Xuanzang staged a hunger strike and was eventually allowed to continue his journey.

Thus, in 630 Xuanzang resumed his travels, armed with introductions to all the rulers along his route (including the ruler of the Western Turks who controlled the region up to India). No longer a fugitive, he was now a pilgrim with official standing. Managing to avoid robbers and other hazards, he reached Sogdiana, where he spent time in Samarkand . While in Samarkand, he went in search of Buddhist temples, only to find them abandoned. Xuanzang describes how, on investigating one of the monasteries, his disciples were attacked by a group of Sogdians who believed in Mazdaism. Xuanzang eventually gained an audience with the king of Samarkand, who saw that the locals were punished for their assault. Having won the king’s favor, the pilgrim was allowed to hold an assembly at which he ordained a number of new monks.

Heading south, Xuanzang passed through Bactria (modern-day southern Uzbekistan and northern Afghanistan), and finally reached northern India. He remained in India for over a decade, spending the main portion of this time at the Nalanda Monastery, southwest of modern Bihar , but also traveling throughout the region, touring monasteries and other Buddhist sites. All the while, he studied Buddhist texts and engaged in religious and philosophical debates with Hindu Brahmins, Jains, and heterodox Buddhists. During this time he acquired a masterful knowledge of Buddhism, and collected numerous Buddhist manuscripts, relics, and statues to carry back to China.

In 643 Xuanzang began his return via Central Asia, crossing the Pamir Mountains to Dunhuang after gaining permission from Emperor Taizong to return. He arrived in Chang’an in the first month of the Chinese lunar year 645 to great celebration. Xuanzang then devoted the rest of his life to translating the Sanskrit manuscripts he had collected. During the same time, he wrote an account of his travels, The Great Tang Records on the Western Regions. The work provides a firsthand glimpse of the cultures, politics, and religions along his route. Indeed, Xuanzang’s narrative is one of the few surviving primary sources on the Sogdians. However, the narrative should be read with a certain caution, since some of the events he described seem unlikely, or certainly embellished. Take, for instance, Xuanzang’s claim that the King of Samarkand warmed to him so quickly that he was allowed to preach and convert locals to Buddhism. It is quite probable this is exaggerated; more likely, the king wished to impress Xuanzang to gain China’s support in case Samarkand broke from Turkish rule. Still, Xuanzang’s account remains one of the most illuminating and important texts we have about life along the Silk Road.

Sally Hovey Wriggins, The Silk Road Journey with Xuanzang (Boulder, CO, and Oxford: Westview Press, 2004), 21–22.

Sally Hovey Wriggins, The Silk Road Journey with Xuanzang (Boulder, CO, and Oxford: Westview Press, 2004), 25.

Sally Hovey Wriggins, The Silk Road Journey with Xuanzang (Boulder, CO, and Oxford: Westview Press, 2004), 38–39.

Samuel Beal, Si-Yu-Ki: Buddhist Records of the Western World Translated from the Chinese of Huien Tsiang (A.D. 629), 2 vols. (London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co., 1906).

Sally Hovey Wriggins, The Silk Road Journey with Xuanzang (Boulder, CO, and Oxford: Westview Press, 2004), 38; Gaybullah Babayarov, The Tamgas of the Co-ruling Ashina and Ashida Dynasties as Royal Tamgas of the Turkic Kaghanate (2006). Available online: https://www.academia.edu/14864292/Babayarov_G._The_Tamgas_of_the_Co-Ruling_Ashina_and_Ashida_Dynasties_as_Royal_Tamgas_of_the_Turkic_Kaghanate

Map showing Xuanzang’s travels.