Sogdian Textiles along the Silk Road

Mariachiara Gasparini

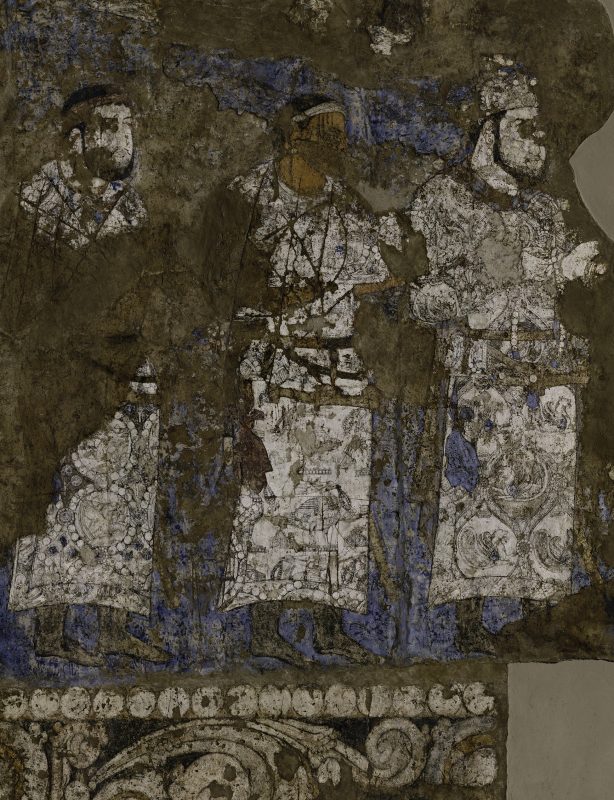

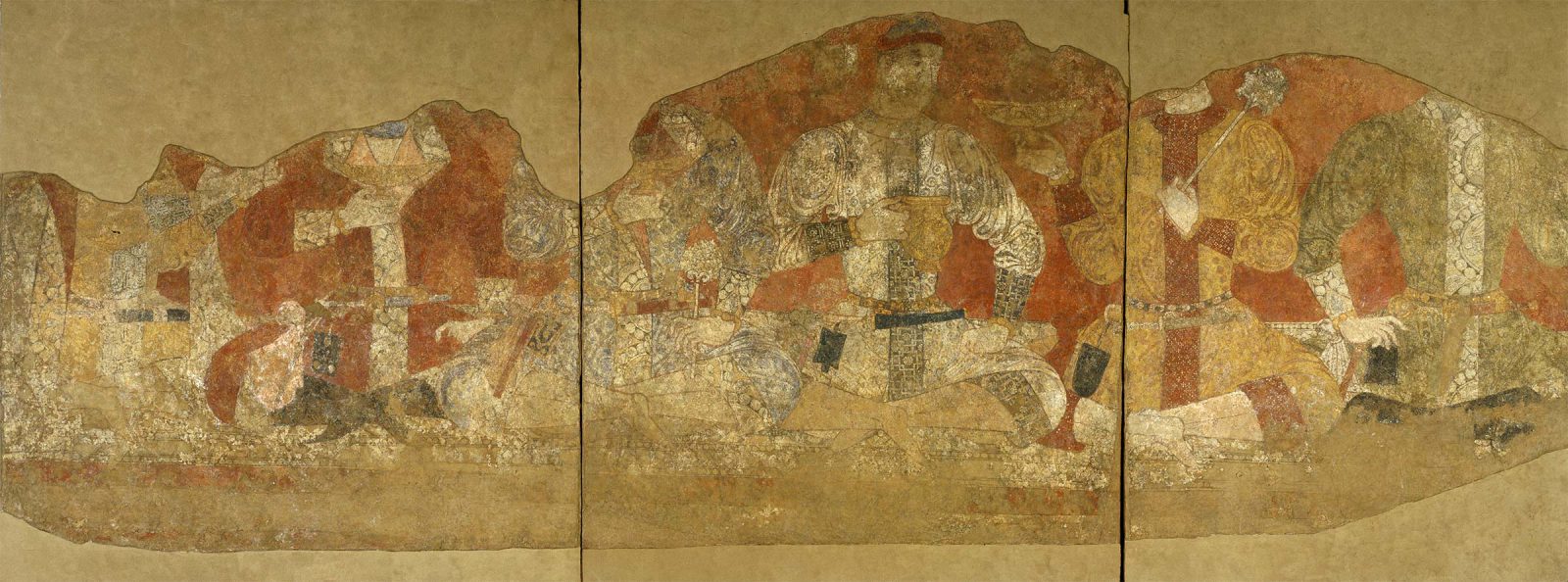

Textile weaving, like metalworking, was a craft in which Sogdian artisans excelled. Although Sogdiana was renowned for cotton textiles, its artisans may have woven polychrome silk weavings as well, as we see these weavings represented in Sogdian wall paintings in the eighth century Fig. 1.

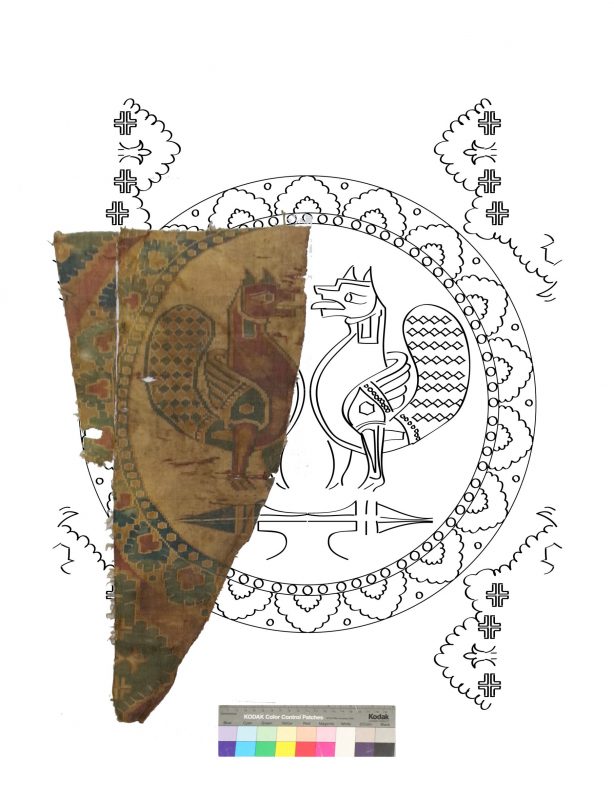

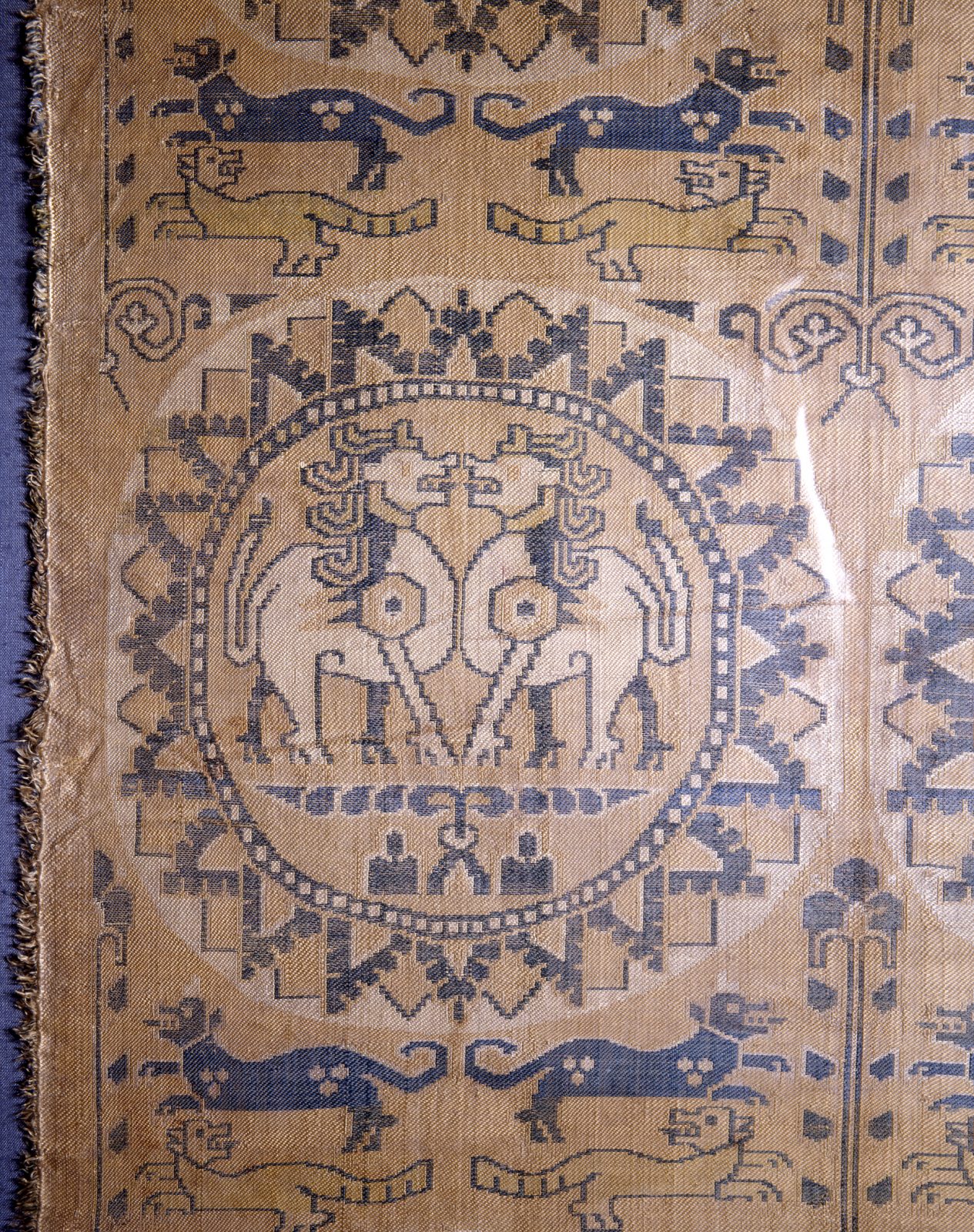

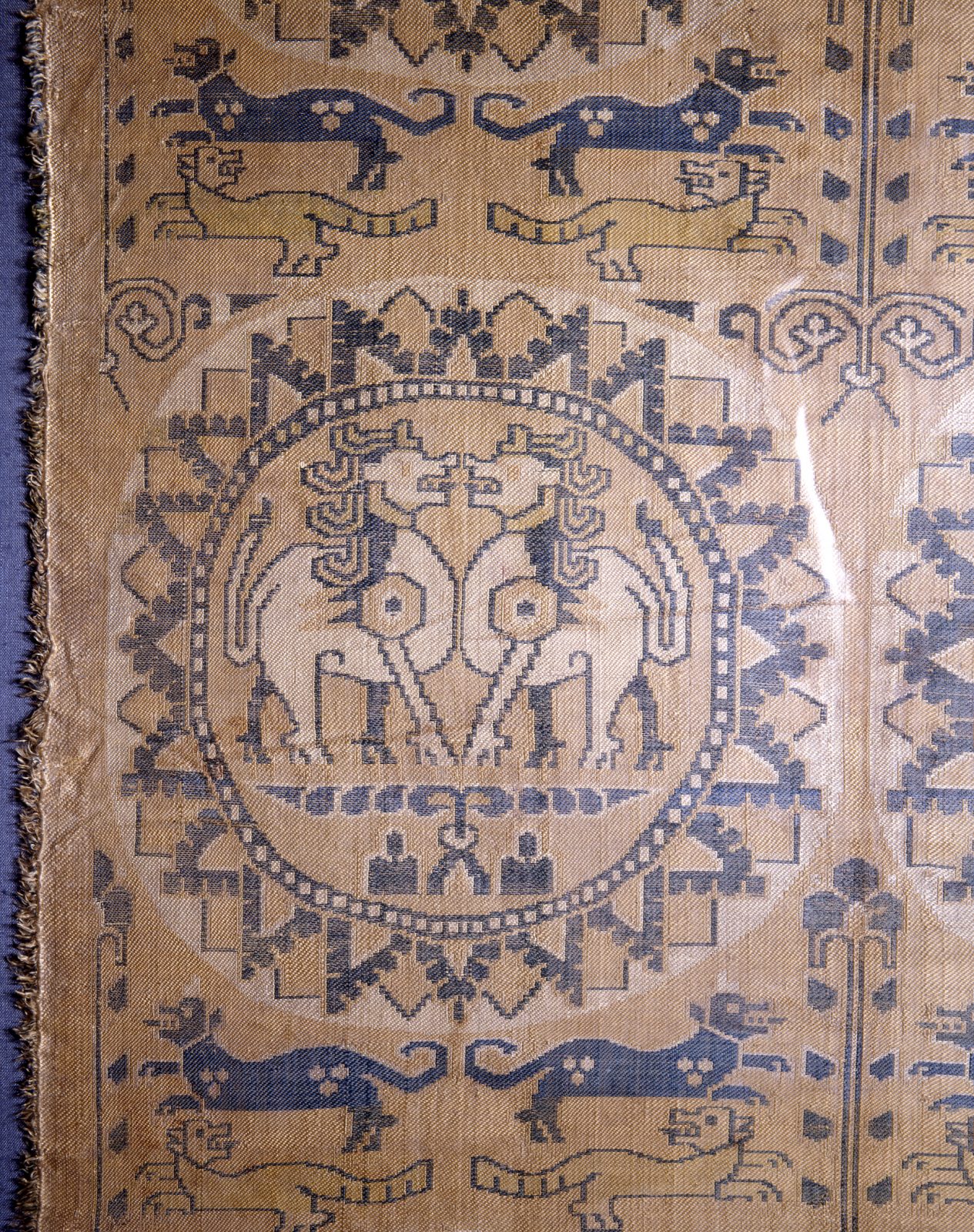

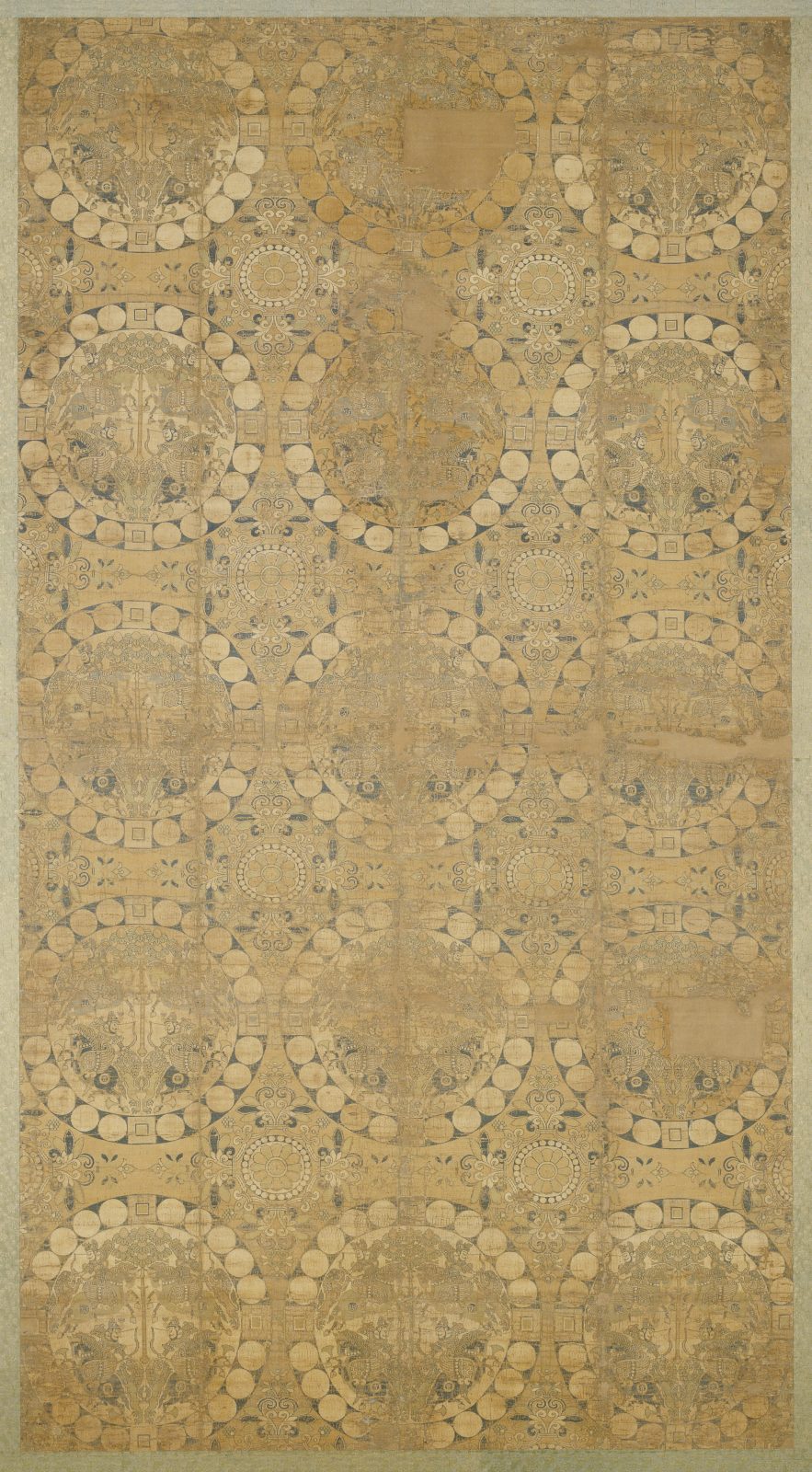

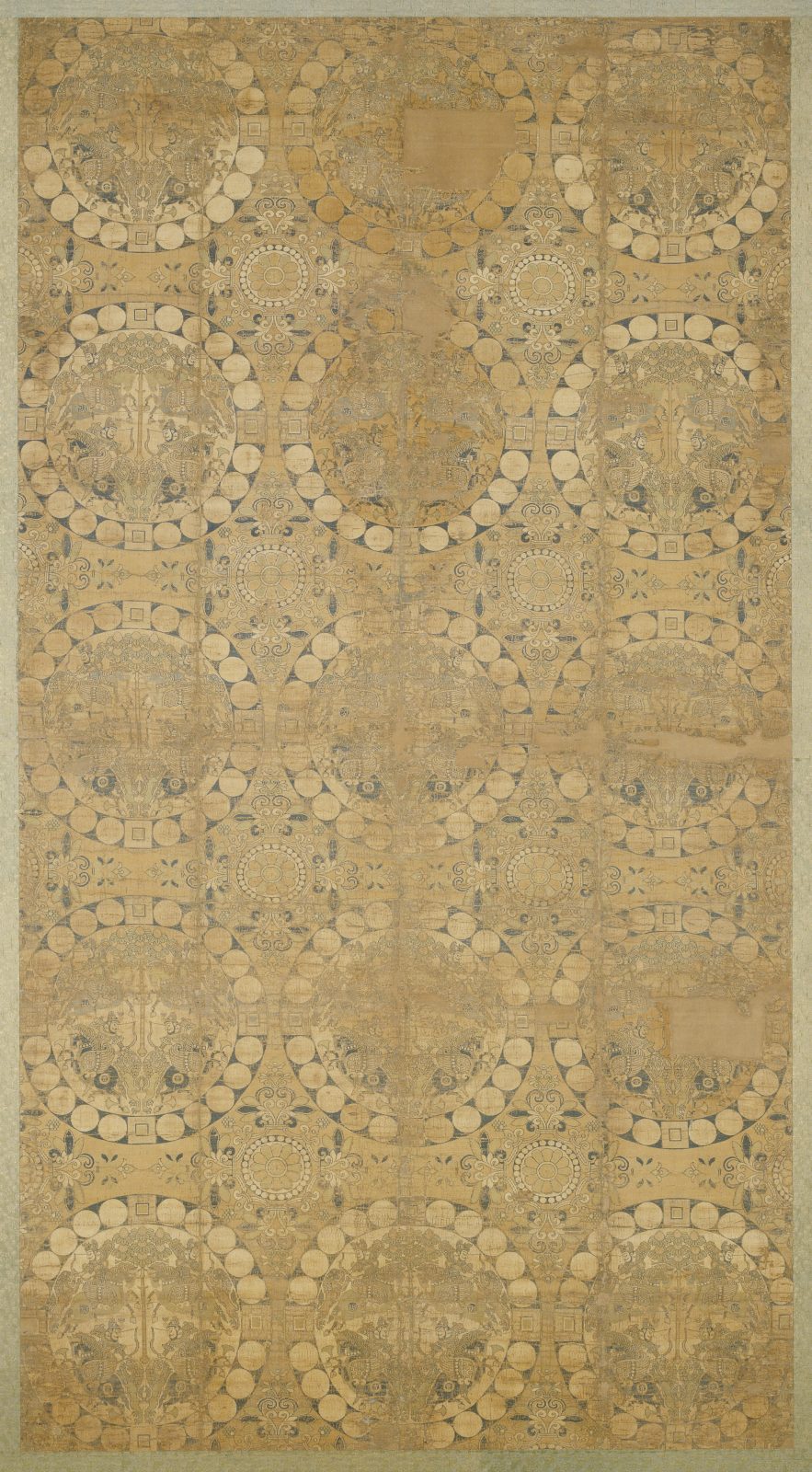

Discovered in China’s northwestern regions, most of these textiles were produced during the early Islamic and Tibetan expansions in Central Asia from the eighth century until the tenth century, Fig. 2 and 3, but the weaving structures and the color palette suggest Sino-Sogdian cooperation that dates back to the fourth or fifth century and that most likely occurred between Sogdiana and the Tarim basin in Xinjiang Province.

Fig. 2-3 Child’s Coat with Ducks in Pearl Medallions. Uzbekistan (probably Sogdia), 700s. Silk: weft-faced compound twill weave (samite). Width across shoulders: 84.5 cm; length back of neck to hem: 51.4 cm. Silk, weft-faced compound twill weave (samite); W. 84.5 cm (across shoulders), 51.4 cm (length back of neck to hem). The Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, 1996.2.1.

Photograph © The Cleveland Museum of Art., Cleveland, Ohio, Purchase from the J. H. Wade Fund 1996.2.1.

Fig. 3 Child’s Coat with Ducks in Pearl Medallions. Uzbekistan (probably Sogdia), 700s. Silk: weft-faced compound twill weave (samite). Width across shoulders: 84.5 cm; length back of neck to hem: 51.4 cm. Silk, weft-faced compound twill weave (samite); W. 84.5 cm (across shoulders), 51.4 cm (length back of neck to hem). The Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, 1996.2.1.

Photograph © The Cleveland Museum of Art., Cleveland, Ohio, Purchase from the J. H. Wade Fund 1996.2.1.

According to Chinese sources, Persian weavings were also reproduced in Sichuan in the seventh century. In these southwestern Chinese regions, colonies of Central Asian—and thus mostly Sogdian— people had established themselves and imported foreign crafts. Most likely due to the high Sasanian trade taxation, the Sogdians began to copy Persian textiles and sell them to the Chinese as “Bosi” 波斯 (Persian). It was to this region that the Sogdian grandfather of the renowned artisan He Chou moved in the sixth century. According to the Chinese categorization and translation of foreign surnames, “He” does, in fact, suggest Sogdian ancestry. He Chou is said to have reproduced a “Persian” golden weaving for the Chinese emperor and “succeeded in making a type even more beautiful” than the original. But actual evidence of golden weavings in China can be dated to the tenth or eleventh century. These weavings are attributed to the Uighurs, who established their Khaganate in Turfan in the ninth century, as well as to the Khitans, founders of the Liao Dynasty (907–1125), and the Jurchen, who founded the Jin Dynasty (1115–1234). Only textile fragments that were stamped or painted with golden motifs or were embroidered in gold can be dated to an earlier period.

Provenance and Evidence

Except for the textiles excavated from the citadel of Mount Mugh and Sanjar-Shah, most Sino-Sogdian textiles (often erroneously categorized as “Sasanian”) have been discovered in the Tarim Basin , Xinjiang , as well as at Moschevaja Balka , Northern Caucasus, and are datable between the seventh and tenth centuries. Generally, these textiles feature zoomorphic and floral motifs, hunting scenes or, rarely, a human bust. Each of these motifs was often enclosed in a beaded or floral medallion; Fig. 4. Other examples, including similar or identical Byzantine types, are found in European cathedral treasuries, probably transported as wrappings brought from the Holy Land or acquired on the art market; a few were excavated in Egypt and attributed to the Sasanians; Fig. 5. In Chinese sources, textiles imitating Sogdian or Central Asian types were classified as “foreign patterned textiles” or “barbarian patterned textiles,” or as “Persian” if considered prestigious. These textiles differed from the Chinese types classified as “Han patterned textiles.”

Although wall paintings from Panjikent, Fig. 1, and Afrasiab, Fig. 6, in Sogdiana, and the rock relief of Taq-e-Bostan in Iran would confirm the broad use of such textile iconographies in these territories, to date, woven or embroidered textiles of these types have not yet been discovered in situ. Material evidence has been excavated only in outer regions. Other pictorial evidence of such early textiles appears in the paintings in Bamiyan in Afghanistan, in the Kizil caves in Xinjiang , and in the Mogao Grottoes in Dunhuang, Gansu. Further east, in Taiyuan, Shanxi, in the Northern Qi (550–577) tomb of the general Xu Xianxiu, a female attendant wears a robe decorated with medallions, Fig. 7, containing the head of a bodhisattva or perhaps the Sogdian goddess Nana. Similar textile fragments or clothing have more recently appeared on the art market and are often attributed to Sogdiana or other Central Asian areas.

Fig. 6 Hall of the Ambassadors, Afrasiab (present-day Samarkand), Uzbekistan (in ancient Sogdiana), Site XXIII:1, mid-7th century CE. Wall painting; H. 3.4 × W. 11.52 m, Afrasiab Museum.

Photograph by Thorsten Greve © Association pour la sauvegarde de la peinture d’Afrasiab, and Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

Fig. 7 A female attendant in the Xu Xianxiu’s tomb wearing a robe with medallion enclosing a bodhisattva or the goddess Nana. Tiayuan, Shanxi, China 6th century.

Photograph © Paintings on the wall of Xu Xianxiu’s Tomb of Northern Qi Dynasty by Ancient Chinese Tomb Painter, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Silk Sogdian Textiles as Zandanījī

In the last sixty years, these silk textiles decorated with zoomorphic figures, plants, composite scenes, and—rarely—single human figures have been linked to Sogdiana and often categorized as zandanījī. The name zandanījī, which originally referred to cotton textiles produced in Zandana , near Bukhara, was also attributed to silk weavings by Dorothy Shepherd, a curator at the Cleveland Museum of Art, and Walter B. Henning, a scholar of Iranian languages and literature, in 1959.

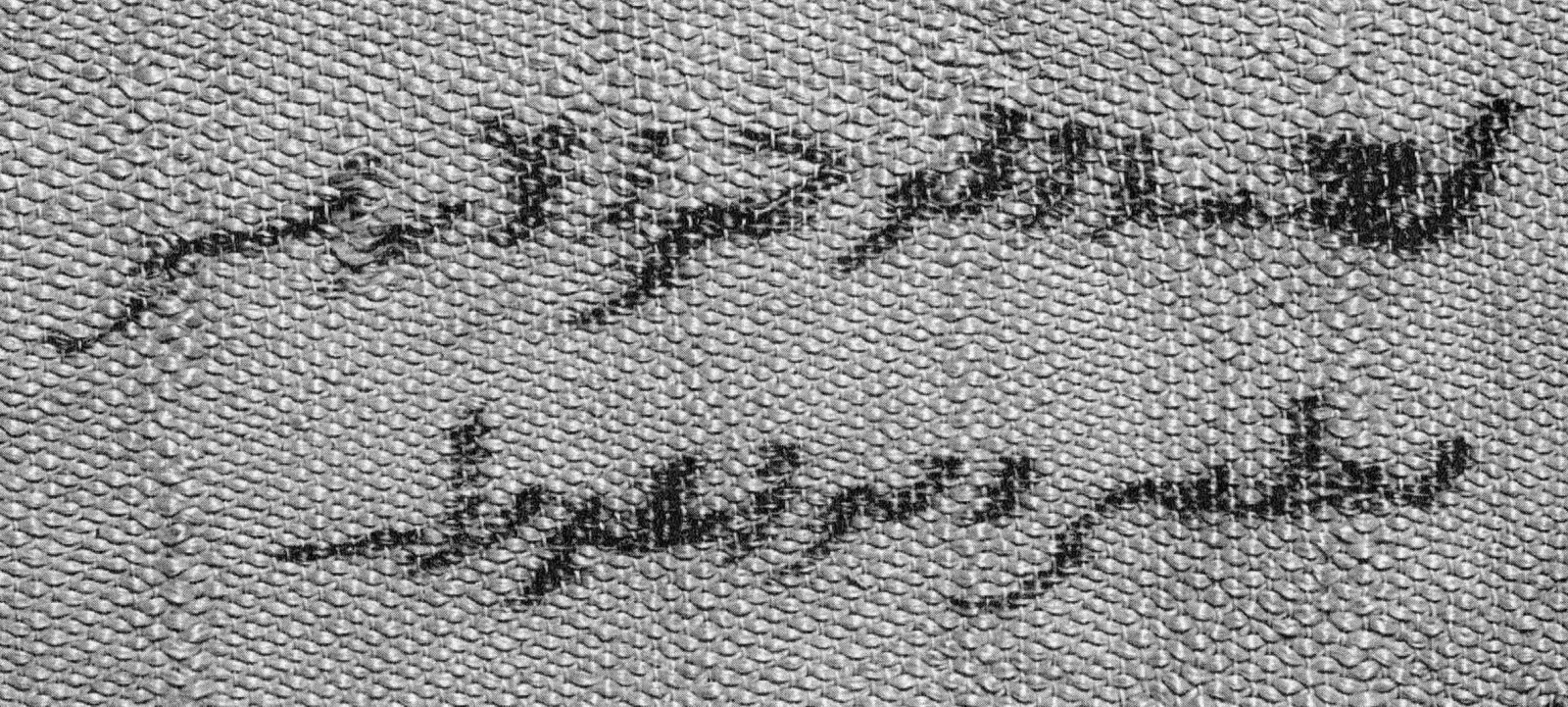

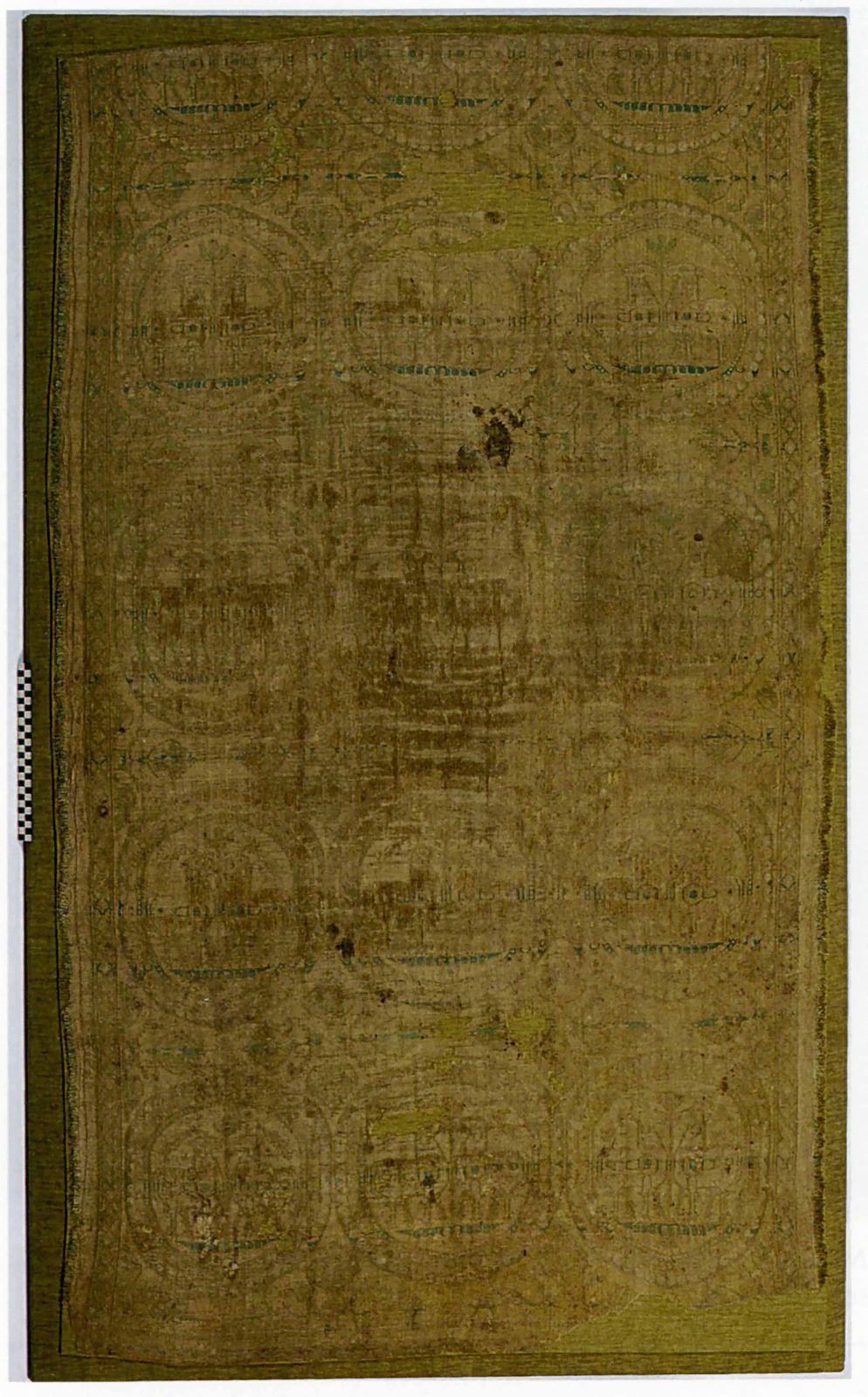

Shepherd distinguished the repetition of medallions enclosing a pair of facing stags that appears on a cloth from Collegiate Church of Notre-Dame in Huy, Belgium, as one of two types of zandanījī (I), Fig. 8 and 9; the other style was based on another piece from the cathedral of Sens, France (II); Fig. 10a,b. A third typology (III) was eventually finalized by Anna Jerusalimskya of the State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, based on the Russian museum’s textile fragments.

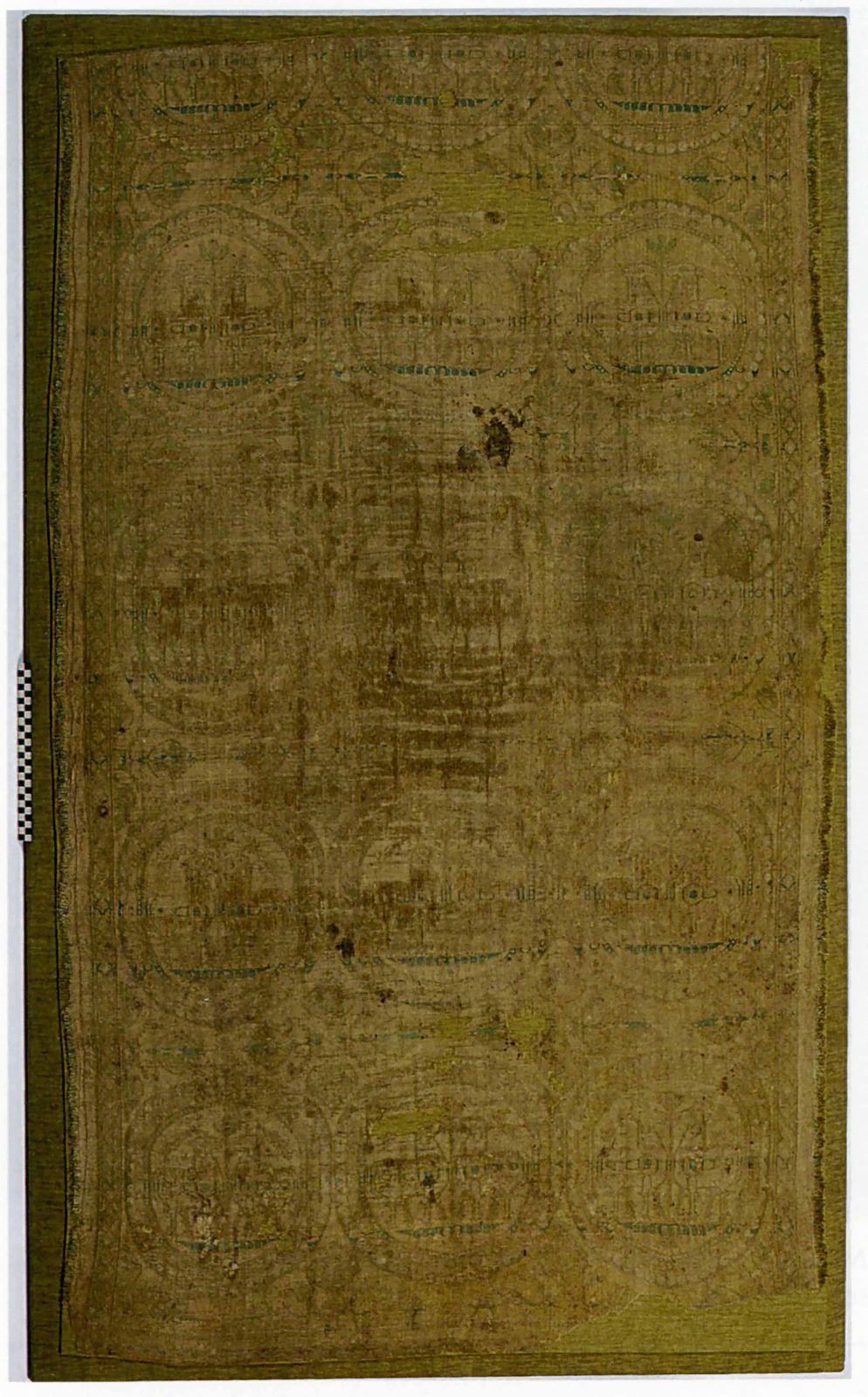

Fig. 8-9 Detail of Arabic inscription from the shroud of St. Mengold and shroud.

Image after Nicholas Sims-Williams and Geoffrey Khan, “Zandaniji Misidentified,” Bulletin of the Asia Institute n.s. 22 (2008 [2012]): 208.

Fig. 10a-b Shroud of St. Columba with lions in pair and close up detail. Silk. Weft-faced compound. Treasure of the Cathédral of Sens, property of the French Ministry of Culture, classified as a historical monument on 26 September, 1903.

Photograph © cl. Musées de Sens – J.-P. Elie.

The name zandanījī began to be attributed to these textiles when Henning recognized an inscription on the piece from Huy as a form of ancient Sogdian and read it as “61 spans of zandanījī”; Fig. 8 and 9.  In n 2009, however, the cloth was radiocarbon dated, and the inscription was reanalyzed by Geoffrey Khan of the University of Cambridge. He recognized it as a ninth-century form of Arabic that referred to a commander named ‘Abd al-Raḥmān, who acquired the cloth for thirty-eight dīnārs. The word “zandanījī”is not mentioned; nonetheless, the term is still often used to categorize these types of textiles.

Weaving Structures and Iconography (Showing the Technique)

The beaded medallion enclosing the above-mentioned zoomorphic and floral motifs, later alternated or substituted by a floral medallion, is emblematic of Sogdian—or Central Asian at large—textile design. These were generally created in a combination of three or four colors (red, yellow, green, and/or blue) and were eventually extended to five or eight colors. Among the dyestuffs found are Kerria lac dye, madder, chay root, and redwood for red; and indigoid dye from woad or other species of Central Asian Indigofera for blue. The combination of some of these dyes created the other colors.

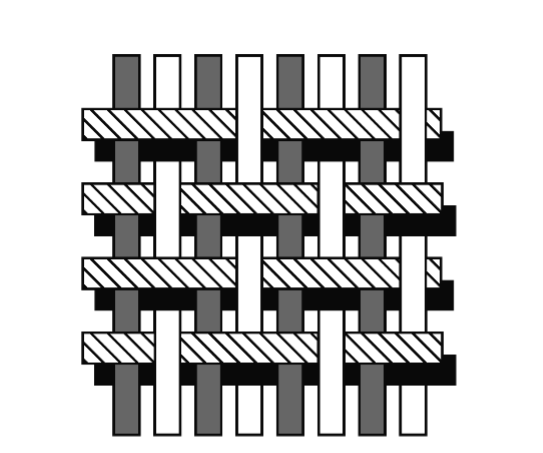

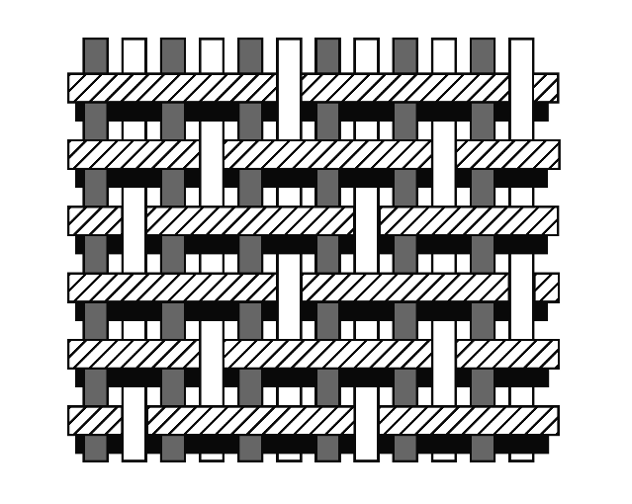

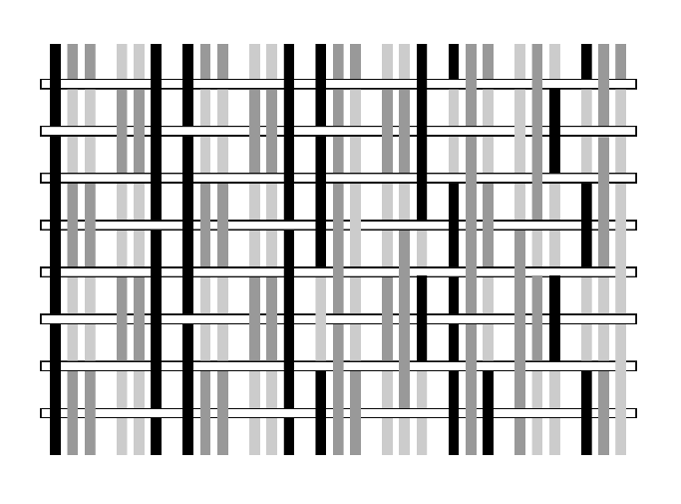

The beaded medallion recalls Byzantine, Iranian, or Central Asian coins, which in China have been found in burials, often pierced for attachment to decorate. In early Islamic texts, however, this circular pattern is described as a celestial vault with stars. As textile patterns (which also appear in other media), they were specially woven in silk weft-faced compounds (tabby or twill), Fig. 11 and 12 , a weaving structure that substituted the Chinese warp-faced compound and which was created with two or more series of warp and one weft. therefore called “weft-faced tabby” or “weft-faced twill.”

The ground and pattern were woven simultaneously, and the entire surface was covered by warp floats to hide the weft; Fig. 13. The weft-faced compound, which became popular around the seventh and eighth centuries, instead made the pattern horizontally. The weave employing a main warp, a binding warp, and a weft was composed of two or more series of threads. The entire surface was covered by weft floats that hid the main warp. This structure could be of two types—tabby and twill—and is therefore called “weft-faced tabby” or “weft-faced twill.”

Similar patterns were also embroidered in silk; nonetheless, the embroidered examples discovered to date have been generally attributed to China; Fig. 14. A few rare examples of woolen tapestry (kilim) coats or silk tapestry (kesi) items with such patterns have also been discovered, some of which can be dated to a later period, around the ninth to the tenth century.

Among the most popular zoomorphic patterns woven in these structures, especially in pairs and facing each other, are winged horses, boars’ heads, rams, stags, ducks, lions, pheasants, and the creature often described as simurgh or senmurv. While many of these appear in the western Chinese Buddhist caves, the so-called simurgh, as it appears in the early Islamic period, is found only on textiles from Qinghai dated to the earlier Tibetan period, and also among Byzantine textiles; Fig. 15.

Fragments with human figures, especially those mirroring hunters, recall similar scenes on Sasanian metalworks. These scenes became popular in both western and eastern territories, embodying the idea of sovereignty over broad territories shared by various Eurasian empires. Examples include a two-jointed fragment discovered in Egypt but likely woven in eastern Iran or Central Asia and inspired by the classical Greco-Roman and Byzantine world, Fig. 16 and 17, and a textile from the temple of Hōryūji in Nara , Japan, showing mirroring royal hunters in pseudo-Sasanian or perhaps Hephtalite attire with Chinese characters in the bodies of the horses Fig. 18 . The composition suggests collaboration between Sogdian and Chinese weavers, or knowledge of both cultural spheres in the Sogdian-Turfanese area; Fig. 19. A similar fragment was indeed excavated from the Astana Cemetery, Xinjiang, in 1967.

Fig. 18 Textile fragment with four mirroring Sasanian kings hunting in Parthian shot position and lions enclosed in a beaded medallion. In the horse bodies, there are the Chinese characters shan 山 (mountain) and ji 吉 (auspiciousness). Silk. Weft-faced compound twill. 250 × 130 cm.

Hōryūji, Nara, Japan. Photograph © Nara National Museum

Conclusion

Because so little has been found in Sogdiana to date, it is not possible to confirm those textiles, mislabeled zandanījī or “Sasanian,” as properly Sogdian. Visual evidence from Penjikent and Afrasiab shows a repertory of images that can be broadly linked to the Sasanian sphere, but that, once acquired in Central Asia through metalworks and possibly textiles (of which no evidence has survived), developed into specific Sogdian-Turfanese weavings which combined Western iconography with Chinese material and technique, as is seen from the material excavated mainly in Xinjiang, Gansu, and Sichuan. During the Tang period, colonies of Sogdians and other Central Asian people were established in Chinese territories. As demonstrated by the Sino-Sogdian tombs discovered, Sogdian sabao (chiefs or caravan leaders) were integrated into the cosmopolitan Chinese society of the time. Nonetheless, in accordance with the Chinese imperial edict, patterned textiles continued to be used only by foreign peoples and, sometimes, by Chinese women who were sent as brides to western chiefs or rulers. For such reasons, due to the lack of these particular types of textiles from central Iran or central China, and based on the color palette and the structure of the fragments discovered, we can only refer to these textiles as Central Asian.

Cf. Mariachiara Gasparini, Transcending Patterns: Silk Road Cultural and Artistic Interactions Through Central Asian Textile Images (University of Hawai’i Press, 2019); Matteo Compareti, “Persian Textiles in the Biography of He Chou: Iranian Exotica in Sui-Tang China,” in Afarin Nameh: Essays on the Archaeology of Iran in Honour of Mehdi Rahbar, ed. Yousef Moradi with Susan Cantan, Edward J. Keall, and Rasoul Boroujeni (Tehran: The Research Institute of Cultural Heritage and Tourism [RICHT], 2019), 165–172.

Etienne de la Vaissière, Sogdian Traders: A History, trans. James Ward (Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2005), 34–37; 144–145; Compareti, “Persian Textiles,” 165–172.

Gasparini, Transcending Patterns, 77; 90; 136–137.

Cf. Anna M. Muthesius, Studies in Byzantine, Islamic, and Near Eastern Silk Weaving (London: The Pindar Press, 2008); and “The Impact of the Mediterranean Silk Trade on Western Europe Before 1200 AD,” in Textile Society of America Society Symposium Proceedings, 1990. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/613/

Documents from Dunhuang P.2613, P.3432, P.4908, P.49.75V, and S.4215 in the Paul Pelliot Collection in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, and Sir Aurel Stein Collection in the British Library, respectively.

Matteo Compareti, “Assimilation and Adaptation of Foreign Elements in Late Sasanian Rock Reliefs at Taq-i Bustan,” in Sasanidische Spuren in der byzantinischen, kaukasischen und islamischen Kunst und Kultur/Sasanian Elements in Byzantine, Caucasian and Islamic Art and Culture, ed. Neslihan Asutay-Effenberger and Falko Daim (Mainz: Verlag des Römisch-Germanischen Zentralmuseums, 2019), 19–36.

Mariachiara Gasparini, “Sino-Iranian Textile Patterns in Trans-Himalayan Areas,” Silk Road Journal 14 (2016): 84–96.

Dorothy G. Shepherd and Walter B. Henning, “Zandanījī Identified?” in Aus der Welt der Islamischen Kunst: Festschrift für Ernst Kühnel zum 75. Geburtstag am 26.10.1957 , ed. Richard Ettinghausen (Berlin: Gebr. Mann, 1959), 15–40.

Dorothy Shepherd, “Zandanījī Revistied,” in Documenta Textilia: Festschrift für Sigrid Müller-Christensen, ed. Sigrid Müller-Christensen, Mechthild Lemberg, and Karen Stolleis (Munich: Deutscher Kunstverlag, 1980), 105–122.

Nicholas Sims Williams and Geoffrey Khan, “Zandanījī Misidentified,” Bulletin of the Asia Institute 22 (2008 [2012]): 210.

Chris Verehcken-Lammens et al., “Radio-Carbon Dated Silk Road Samites in the Collection of Katoen Nataie, Antwerp,” Iranica Antiqua XLI (2006): 233–301.

Lin Ying, “Solidi in China and Monetary Culture Along the Silk Road,” Silk Road Journal, 2 (2010): http://www.silkroadfoundation.org/newsletter/vol3num2/4_ying.php

Matteo Compareti, “The Wild Boar Head Motif among the Paintings in Cave 420 at Dunhuang,” Journal of the Silk Road Studies 丝绸之路研究集刊 6 (2021): 284–302.

Matteo Compareti, “Iranian Composite Creatures between Caucasus and Western China: The Case of the So-Called Simurgh,” Iran and Caucasus 24 (202): 115–138.

Jin Xu, “Symbols of Universal Kingship: A Study of the Imagery on the Brocade with Lion Hunting in the Horyuji Temple,” Sino-Platonic Papers 307 (2021): 1–36.

Zhao Feng, “The Development of Pattern Weaving Technology through Textile Exchange Along the Silk Road” in Global Textile Encounter, ed. Marie-Louise Nosch, Zhao Feng and Lotika Varadarajan (Oxford: Oxbow Books, 2014), Fig. 6.6.

Discussed by Buyun Chen in Empire of Style: Silk and Fashion in Tang China (University of Washington Press, 2019).

A few fragments from the same period have been discovered in Chang’an (present Xi’an), former capital of the Tang empire, and are now held in the Shanxi History Museum.

Sogdian Banqueters. Panjikent, Tajikistan (ancient Sogdiana), Site XVI:10, first half of 8th century. Wall painting; H. 136 cm × W. 364 cm. The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, SA-16215-16217.

Photograph © The State Hermitage Museum

Child’s Coat with Ducks in Pearl Medallions. Uzbekistan (probably Sogdia), 700s. Silk: weft-faced compound twill weave (samite). Width across shoulders: 84.5 cm; length back of neck to hem: 51.4 cm. Silk, weft-faced compound twill weave (samite); W. 84.5 cm (across shoulders), 51.4 cm (length back of neck to hem). The Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, 1996.2.1.

Photograph © The Cleveland Museum of Art., Cleveland, Ohio, Purchase from the J. H. Wade Fund 1996.2.1.

Child’s Coat with Ducks in Pearl Medallions. Uzbekistan (probably Sogdia), 700s. Silk: weft-faced compound twill weave (samite). Width across shoulders: 84.5 cm; length back of neck to hem: 51.4 cm. Silk, weft-faced compound twill weave (samite); W. 84.5 cm (across shoulders), 51.4 cm (length back of neck to hem). The Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, 1996.2.1.

Photograph © The Cleveland Museum of Art., Cleveland, Ohio, Purchase from the J. H. Wade Fund 1996.2.1.

Leggings. Caucasus region, ca. 7th–9th century CE. Silk and linen; 80.01 cm. Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1996. 1996.78.2a, b. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1996. 1996.78.2a, b.

Photograph © The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Textile fragment with winged horses. Silk weft-faced fragment from Antinopolis, Egypt. Ca. 6th–7th cent. Lyon, Musée des Tissus MT 26812.11.

Photograph © Pierre Verrier

Hall of the Ambassadors, Afrasiab (present-day Samarkand), Uzbekistan (in ancient Sogdiana), Site XXIII:1, mid-7th century CE. Wall painting; H. 3.4 × W. 11.52 m, Afrasiab Museum.

Photograph by Thorsten Greve © Association pour la sauvegarde de la peinture d’Afrasiab, and Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

A female attendant in the Xu Xianxiu’s tomb wearing a robe with medallion enclosing a bodhisattva or the goddess Nana. Tiayuan, Shanxi, China 6th century.

Photograph © Paintings on the wall of Xu Xianxiu’s Tomb of Northern Qi Dynasty by Ancient Chinese Tomb Painter, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Detail of Arabic inscription from the shroud of St. Mengold and shroud.

Image after Nicholas Sims-Williams and Geoffrey Khan, “Zandaniji Misidentified,” Bulletin of the Asia Institute n.s. 22 (2008 [2012]): 208.

Shroud of St. Mengold. Eastern provinces of the Abbassid Caliphate, 8th–9th century CE. Polychrome silk, L. 1.92 x W. 1.22 m. Collegiate Church of Notre-Dame, Huy, Belgium.

Image after Nicholas Sims-Williams and Geoffrey Khan, “Zandaniji Misidentified,” Bulletin of the Asia Institute n.s. 22 (2008 [2012]): plate 8.

Shroud of St. Columba with lions in pair and close up detail. Silk. Weft-faced compound. Treasure of the Cathédral of Sens, property of the French Ministry of Culture, classified as a historical monument on 26 September, 1903.

Photograph © cl. Musées de Sens – J.-P. Elie.

Close up of Shroud of St. Columba with lions in pair and close up. Silk. Weft-faced compound. Treasure of the Cathédral of Sens, property of the French Ministry of Culture, classified as a historical monument on 26 September, 1903.

Photograph © cl. Musées de Sens – J.-P. Elie.

Weft-faced tabby structure.

M. Gasparini

Weft-faced twill structure.

M. Gasparini

Warp-faced structure.

M.Gasparini

Textile fragment with boar’s head medallions. Silk split-stich embroidery on plain silk. 7th century. Central Asia or China. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2004.260.

Photograph © The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Two textile fragments showing a standing simurgh and reconstruction by M. Gasparini. 8th–9th century. Silk weft-faced compound. Possibly from Qinghai. China National Silk Museum 3440.1-1.

Image reconstruction by M. Gasparini (Gasparini 2019, plate 12).

Roundels with hunters. Eastern Iran or Central Asia, 800s. Samite: silk. 26.5 × 25.5 cm (10 7/16 × 10 1/16 in.). Eastern Iran or Central Asia. Found in an Egyptian tomb. Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, 1959.124.

Photograph © The Cleveland Museum of Art.

Plate with youths and winged horses. Ca. 5th–6th century. Silver, mercury gilded. H. 5.2 × Diam. 21 cm, 572g (2 1/16 × 8 1/4 in.). Iran. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (63.152).

Photograph © The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Textile fragment with four mirroring Sasanian kings hunting in Parthian shot position and lions enclosed in a beaded medallion. In the horse bodies, there are the Chinese characters shan 山 (mountain) and ji 吉 (auspiciousness). Silk. Weft-faced compound twill. 250 × 130 cm.

Hōryūji, Nara, Japan. Photograph © Nara National Museum

Textile fragment with four mirroring Sasanian kings hunting in Parthian shot position and lions enclosed in a beaded medallion. In the horse bodies, there are the Chinese characters shan 山 (mountain) and ji 吉 (auspiciousness). Silk. Weft-faced compound twill. 250 × 130 cm. Hōryūji, Nara, Japan.

Photograph © Nara National Museum

Plate with King Hormizd II or III hunting lions. 4th–5th century. Silver gilt. 4.6 × 20.8 cm (1 13/16 × 8 3/16 in.). Iran. Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, 1962.150. Photograph © The Cleveland Museum of Art.

Photograph © The Cleveland Museum of Art.