Sogdian Language and Its Scripts

by Nicholas Sims-Williams

Sogdian is a language belonging to the Iranian branch of the Indo-European language family. It was originally spoken in an area centered on Samarkand in present-day Uzbekistan, and extending from Bukhara in the west to Tashkent (ancient Chach) in the northeast; Fig. 1.

Sogdian merchants set up trading posts along the so-called “Silk Roads” deep into China and even Mongolia. As a result, Sogdian came to be spoken and written over a very wide area, both as a native language and as a lingua franca used by people who were native speakers of other languages. In fact, the great majority of the Sogdian materials known today were not found in Sogdiana but in the Turfan oasis and Dunhuang in western China; Fig. 2.

In the 6th to 4th centuries BCE, Sogdiana formed part of the Achaemenid Empire of Darius I and his successors. The language most widely used for long-distance communication throughout this huge area was Aramaic, which could be conveniently written in ink on portable materials such as papyrus or parchment. In Sogdiana, as in most other parts of the empire after its breakup, when the local language began to be written, it was naturally the Aramaic script that people employed for the purpose. In each region the Aramaic script developed different local characteristics, eventually giving rise to the distinct scripts known as Parthian, Choresmian, Sogdian, and so on. These retained many features of the underlying Aramaic script, including the direction of writing (from right to left) and a standard alphabet of twenty-two letters, all of which basically represent consonants, the vowels being indicated only approximately if at all. More remarkably, they also preserve the Aramaic written form of many words. Thus the preposition “from” is written in its Aramaic spelling mn in almost all Middle Iranian languages, but is read differently in each: as az in Middle Persian, as až in Parthian, and as ač or čan in Sogdian. Such Aramaic spellings for Iranian words are referred to as “logograms” or “ideograms.”

Fig. 3 Nicholas Sims-Williams (School of Oriental and African Studies) provides an overview of the Sogdian language.

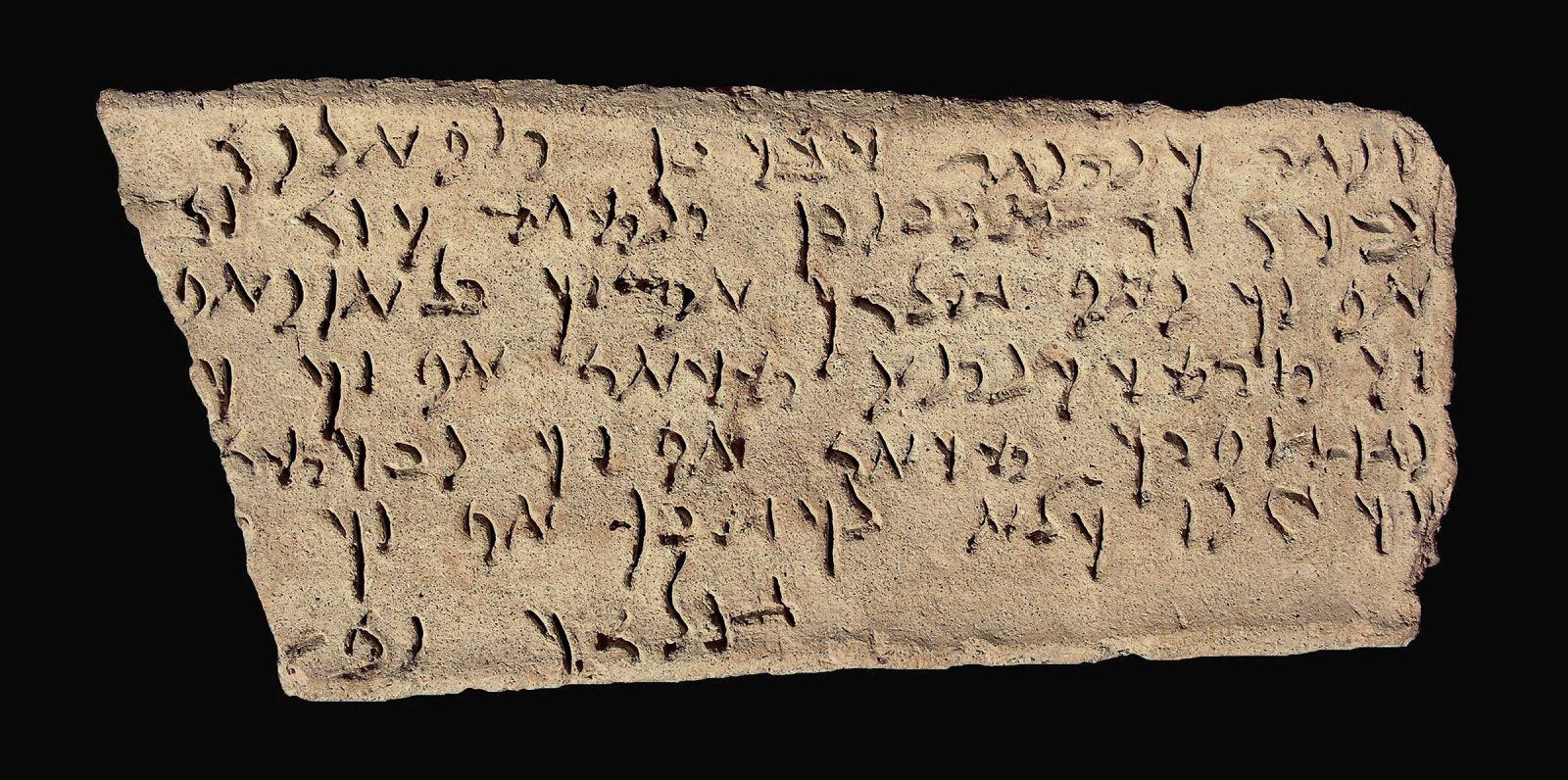

The earliest Sogdian texts of any significant length are a group of inscriptions on clay plaques found at Kultobe in southern Kazakhstan, to the north of Tashkent, which may date to as early as the 1st or 2nd century CE; Fig. 4. The inscriptions are understood as recording the colonization of the area by Sogdians from the cities of Samarkand , Kesh (Shahr-i-Sabz) , Nakhshab (Karshi) , and Bukhara , under the leadership of a general from Chach (Tashkent) , as well as a division of the land between the Sogdians and the nomadic people of the region. The Kultobe inscriptions are written in an archaic form of the Sogdian script that is still close to its Aramaic prototype. Most words are written with Aramaic logograms, so that only a few phonetic spellings, such as sp’δny [spādh-nī] literally, “army leader”—that is, “general”—reveal that the language is in fact Sogdian.

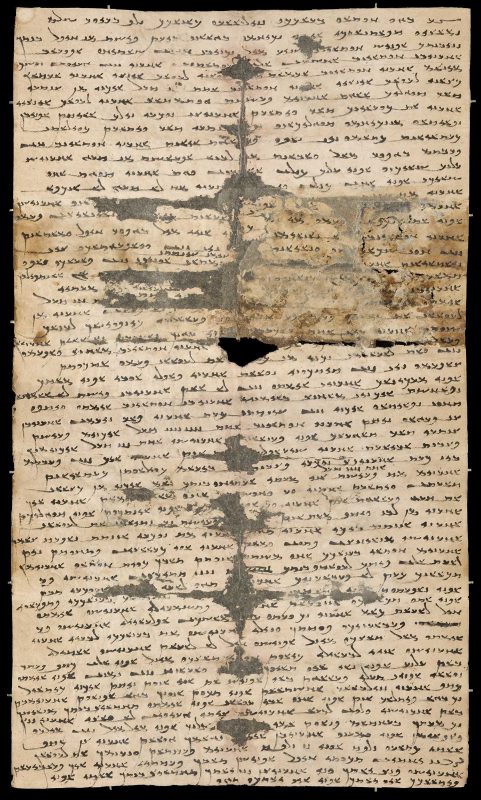

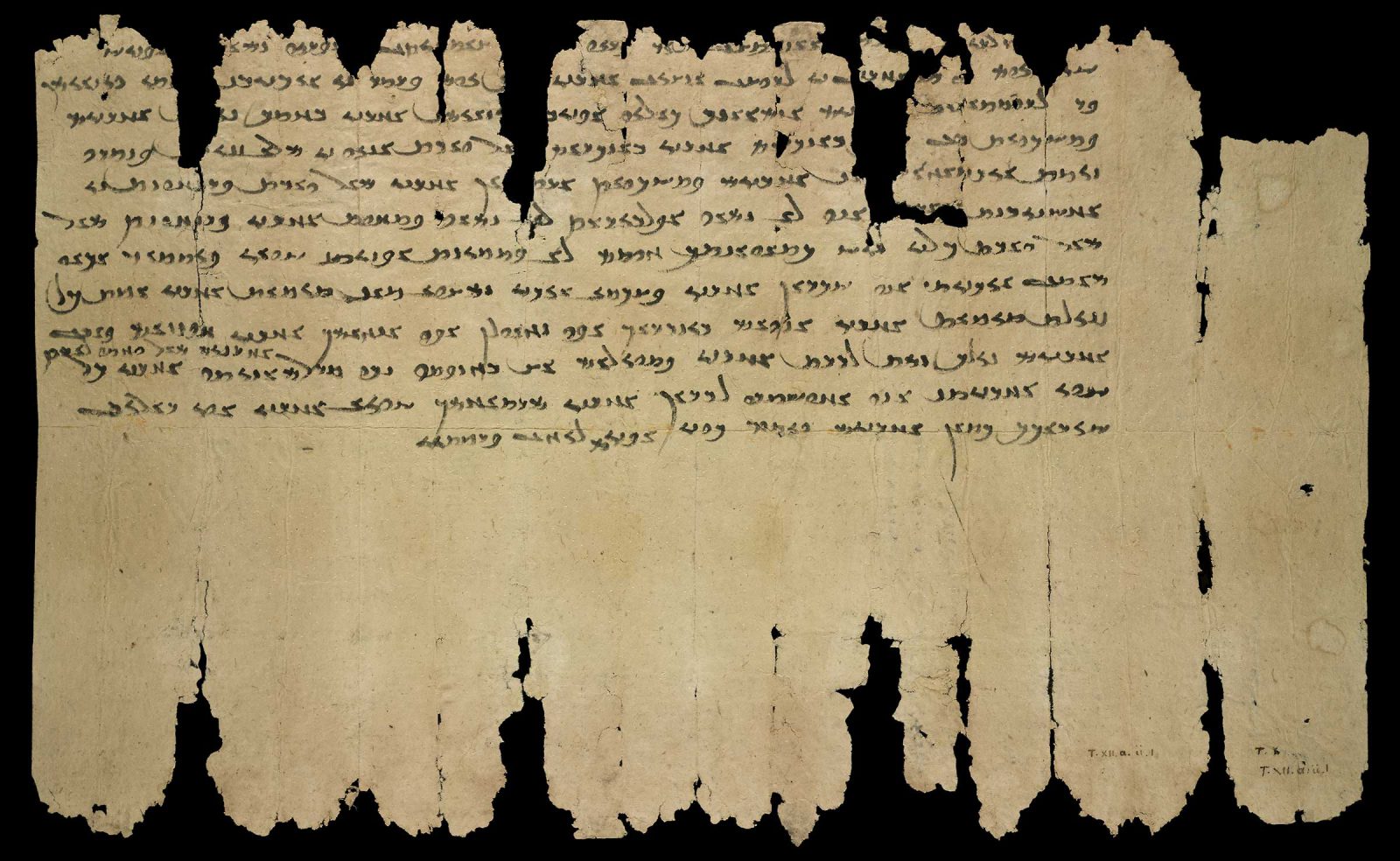

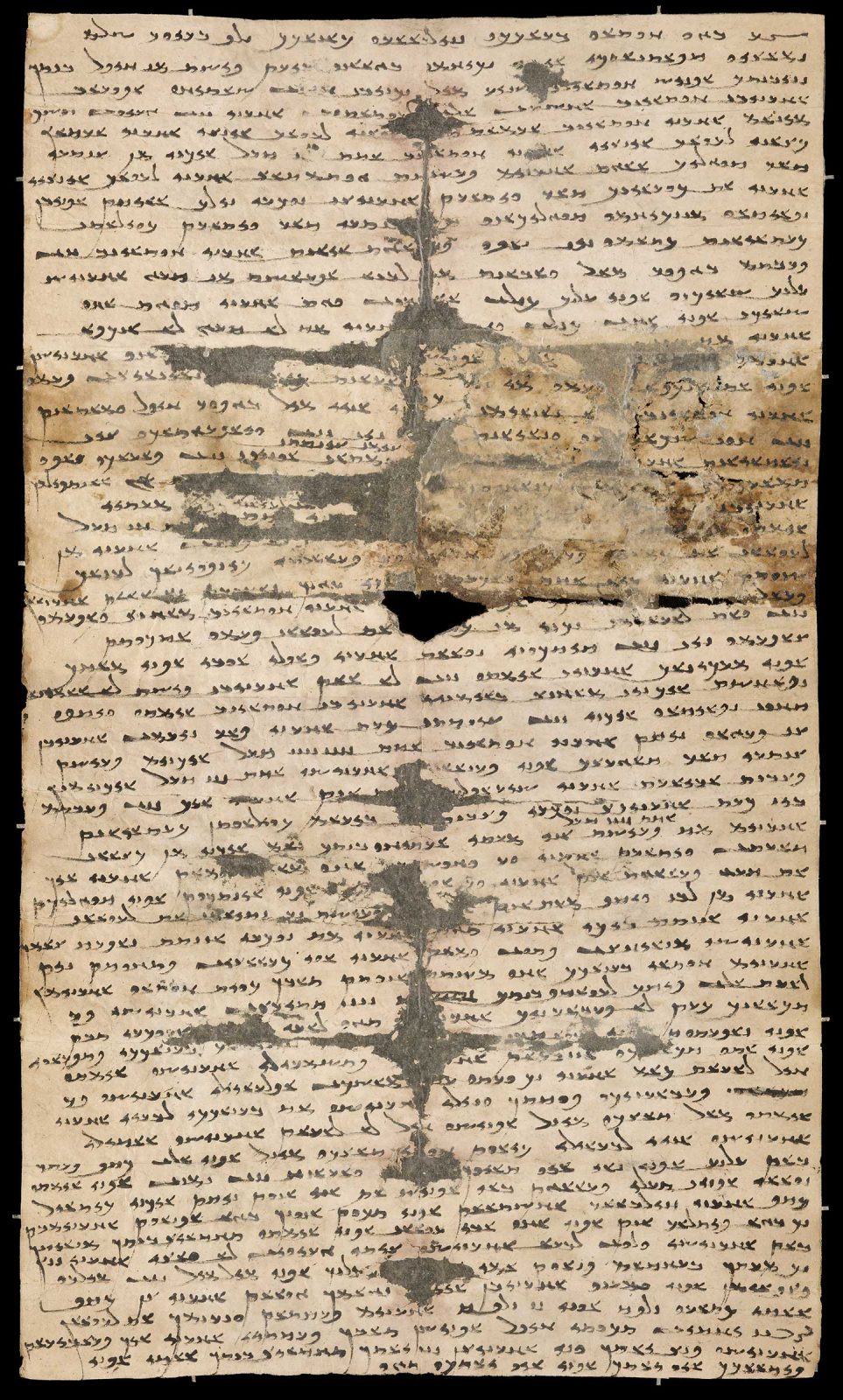

The next important Sogdian texts are the “Ancient Letters,” written in the early 4th century; Figs. 5 and 6. By this time, phonetic spellings are more common than logograms and there is a tendency to join together the individual letters within the word. In the following centuries these developments continue to gather strength.

Fig. 5 Sogdian Ancient Letter 1, recto. View object page

Photograph © The British Library Board.

Fig. 6 Sogdian Ancient Letter 2, 312 or 313 CE. Discovered in 1907 at watchtower (T.XII.A), west of Dunhuang 敦煌, Gansu Province, China. Ink on paper; H. 42 × W. 24.3 cm. The British Library, Or. 8212/95. View object page

Photograph © The British Library Board.

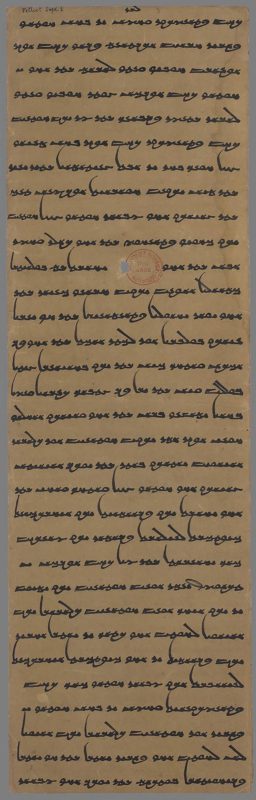

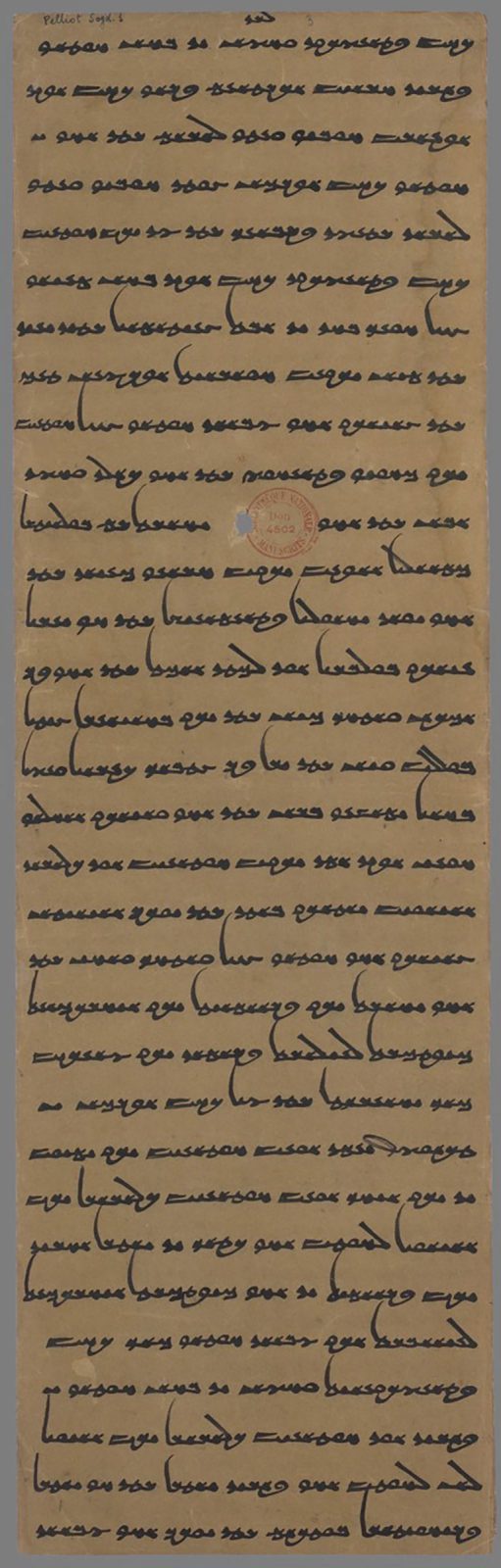

Only the most common words are still written by means of logograms, and the script becomes more and more cursive, as evident in a fragment from an epic tale about the hero Rustam; Fig. 7. A disadvantage of the cursive script is that many letters become difficult to distinguish from one another. This problem would be overcome by the development of a more formal and calligraphic variety of Sogdian script, often referred to as the “sutra script” because it was mainly used for copying Buddhist texts such as the Vessantara Jataka; Fig. 8.

In the late 6th century, the Uighur Turks adopted the Sogdian cursive script and language for writing their earliest inscriptions. Subsequently the same form of writing came to be used for the Turkish language itself, developing into a form known as “Uighur script.” Later still, the same script was borrowed for writing Mongolian and Manchu. A characteristic feature of all these scripts derived from Sogdian was that they were usually written vertically rather than horizontally, a change of orientation that began among the Sogdians themselves as early as the 5th century.

The Sogdian script in its various forms is sometimes referred to as the Sogdian “national script” because it was available to all speakers of the language and used for writing texts of all sorts, including religious texts as well as inscriptions, letters, and legal documents. In addition, adherents of the Manichaean and Christian religions in the Turfan oasis also made use of their own scripts for writing Sogdian as well as other languages.

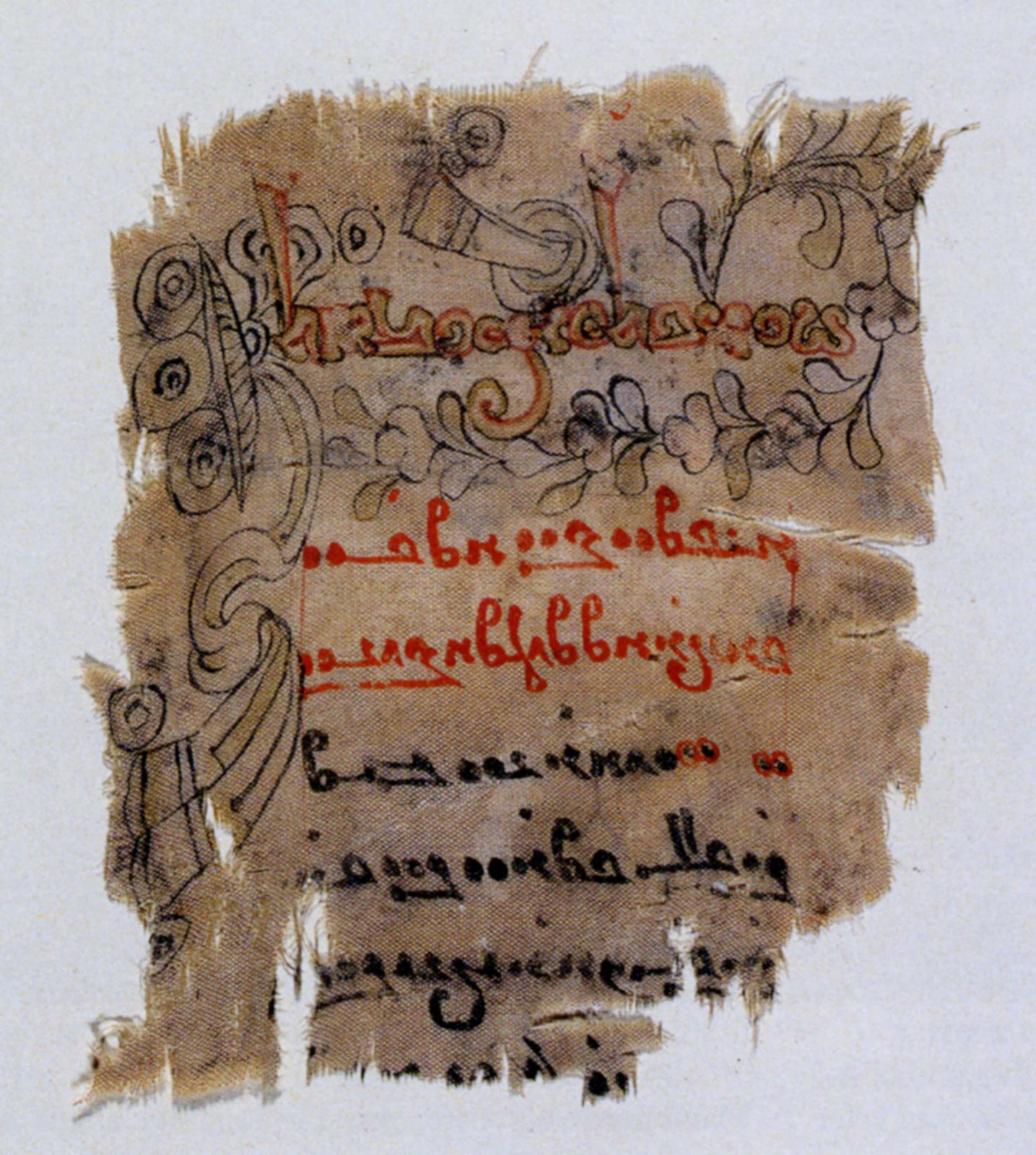

The Manichaean script is a cursive variety of the alphabet used by the people of Palmyra in Syria for writing the Palmyrene dialect of Aramaic; Fig. 9. Because this was the script that Mani, the founder of the Manichaean religion, had used, it had a special status among his followers, who employed it for many different languages. For some of these, including Sogdian, they added extra letters for consonants that the twenty-two letters of the basic Aramaic alphabet could not adequately represent. The Manichaean script, which also lacks the logograms of the Sogdian script, thus gives a clearer representation of at least the consonant sounds of the Sogdian language. Mani was famous not only as the prophet of a new religion but also as an artist. This may, in part, account for the beautiful calligraphy and decoration that distinguishes the manuscripts in Manichaean script.

Fig. 9 Fragmentary decorated Manichean text in Manichean script, ca. mid-8th to early 11th century CE. Ink, pigments, and gold on silk; H. 7.4 x W. 6 cm. Berlin, Museum für Asiatische Kunst: MIK III 4981a.

After Zsuzsanna Gulácsi, Manichaean Art in Berlin Collections (Turnhout: Brepols, 2001), 167, fig. 75.1.

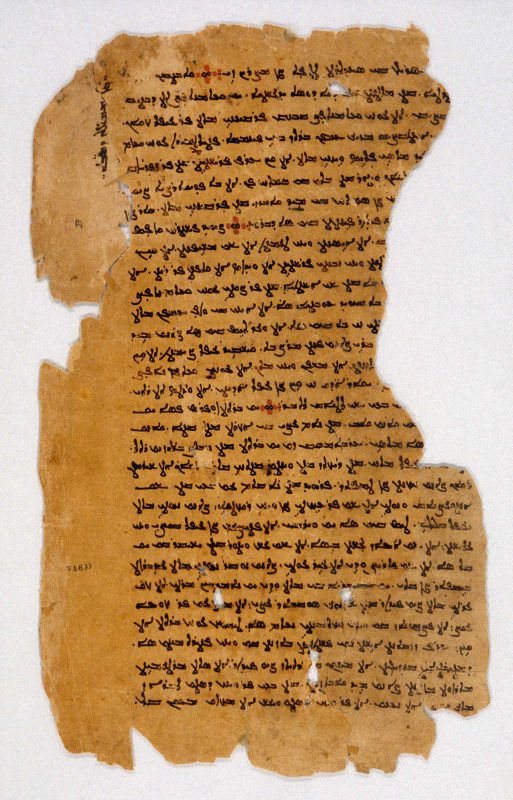

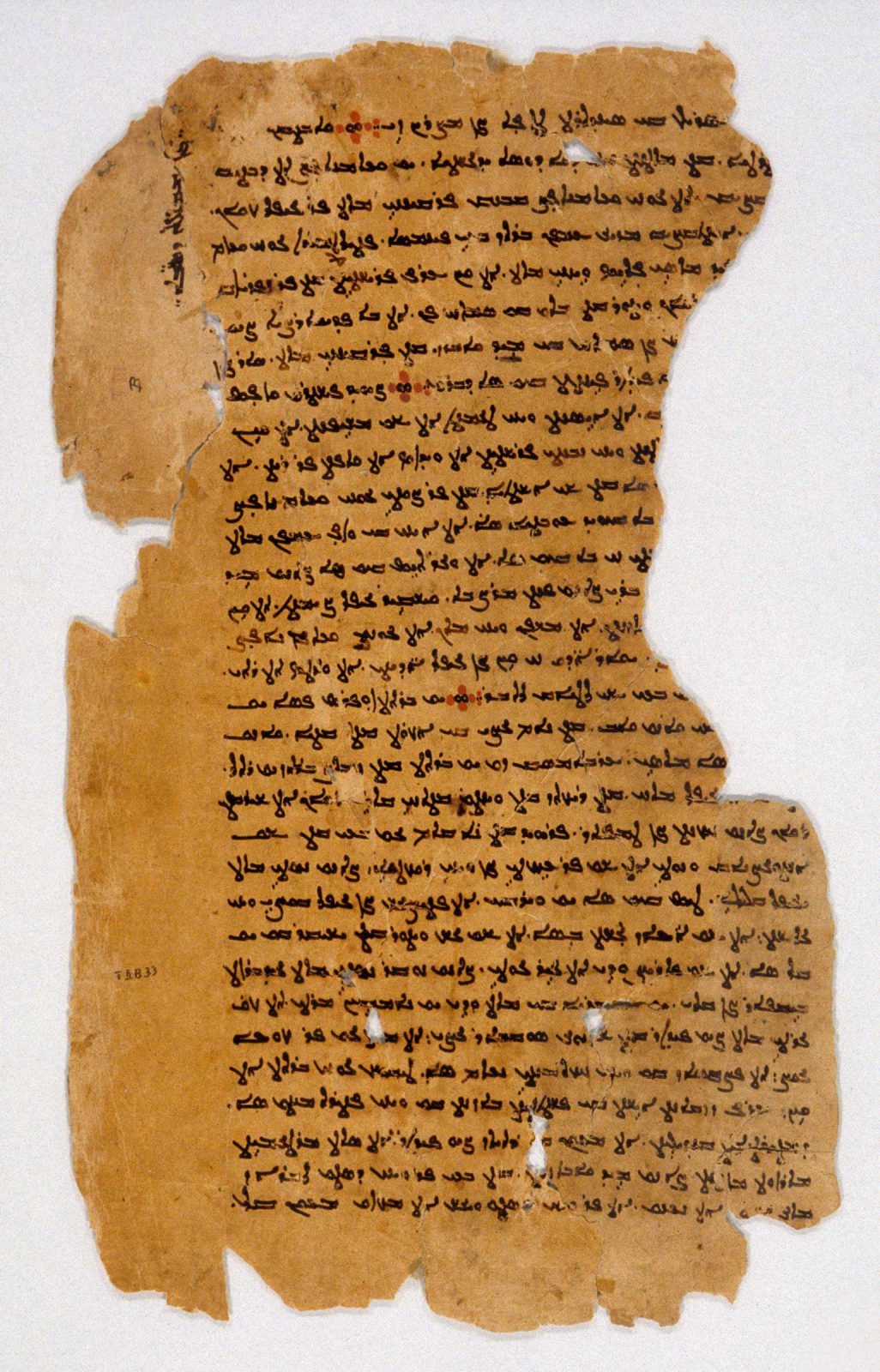

Like the Manichaeans, the Christians also had a special attachment to a particular script, in their case the Syriac script; Fig. 10. This was yet another variant of Aramaic, with the same basic twenty-two letters. For writing Sogdian, three (and sometimes four) extra letters were added, but more importantly, some scribes adopted the East Syrian system of inserting points above and below the letters to distinguish one vowel from another.

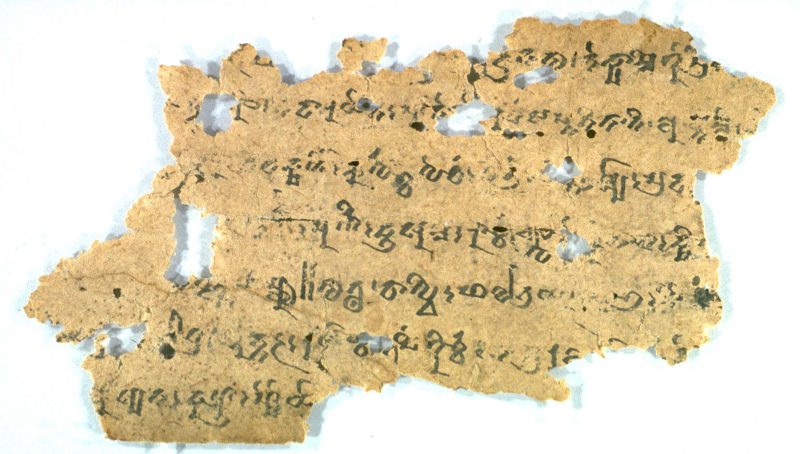

Finally, a very few late Sogdian manuscripts, mostly medical texts, are written in a Central Asian variant of the Indian Brahmi script; (Fig. 11). In principle, this script indicates all vowels, although the value of these manuscripts as evidence for the pronunciation of Sogdian is limited by their poor state of preservation.

Fig. 10 Christian text in Syriac script. Selection from Sayings of the Desert Fathers, entitled “Sayings of the Old Men.” Found in Bulayïq, near Turfan, Xinjiang, ca. 9th century CE. Ink on paper; H. 31.5 x W. 19 cm.

Deposit of Berlin–Brandenburg Academy of Sciences, Berlin State Library—Prussian Cultural Heritage, Orient Dept., n 489, recto.

Fig. 11 Bilingual Sanskrit–Sogdian medical prescription for eye diseases. Presumably from somewhere in the Turfan region, ca. 9th century CE. Ink on paper; H. 10 x W. 14.7 cm.

Deposit of Berlin–Brandenburg Academy of Sciences, Berlin State Library—Prussian Cultural Heritage, Orient Dept., M(ain)z 0639, side 1.

The latest known Sogdian manuscripts of any kind probably date from the 11th century. After that period, Sogdian was no longer used as a written language, having been superseded by Persian and Arabic in Sogdiana, and by Turkish and Chinese in the Turfan oasis and farther East. Sogdian continued to be spoken after this time, and in fact, one Sogdian dialect has survived until the present day in a remote area of Tajikistan , where it is known as Yaghnobi.

Fig. 13 Nicholas Sims-Williams (School of Oriental and African Studies) explores the afterlife of the Sogdian language.

Nicholas Sims-Williams, “Ideographic Writing, i: Terminology and Conventions,” Encyclopaedia Iranica [EIr] 12, no. 6 (New York: Encyclopaedia Iranica Foundation [EIF], 2004), 616–17; and http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/ideographic-writing – i.

Nicholas Sims-Williams, Frantz Grenet, and Aleksandr Podushkin, “Les plus anciens monuments de la langue sogdienne: Les inscriptions de Kultobe au Kazakhstan,” in Comptes-rendus de séances de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres (CRAI) 151 (2007 [2009]): 1005–34.

Nicholas Sims-Williams, “The Sogdian Sound-System and the Origins of the Uyghur Script.” Journal Asiatique 269 (1981): 347–60.

Yutaka Yoshida, “When did Sogdians Begin To Write Vertically?” Tokyo University Linguistic Papers 33 (2013): 375–94.

Nicholas Sims-Williams, “The Sogdian Manuscripts in Brāhmī Script as Evidence for Sogdian Phonology,” In Turfan, Khotan und Dunhuang: Vorträge der Tagung “Annemarie von Gabain und die Turfanforschung,” Berlin-Brandenburgische Akademie der Wissenschaften, Berichte und Abhandlungen, ed. Ronald E. Emmerick, Werner Sundermann, Ingrid Warnke, and Peter Zieme. Special vol. 1 (Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 1996), 307–15.

Map showing the central lands in which Sogdian was spoken.

Map showing Turfan and Dunhuang relative to Sogdiana.

Plaque with Proto-Sogdian Inscription No. 4, 1st–3rd century CE. Baked clay; H. 14 x W. 31 cm. Central State Museum of Kazakhstan, Almaty, KP 26859/1.

Photograph © A. N. Podushkin.

Sogdian Ancient Letter 1, recto.

Photograph © The British Library Board.

Sogdian Ancient Letter 2, 312 or 313 CE. Discovered in 1907 at watchtower (T.XII.A), west of Dunhuang 敦煌, Gansu Province, China. Ink on paper; H. 42 × W. 24.3 cm. The British Library, Or. 8212/95.

Photograph © The British Library Board.

Fragment of Sogdian story of Rustam and the Demons, ca. 9th century CE. Ink on paper, H. 28 x W. 29 cm. The British Library, London. Or. 8212/81 Recto.

Photograph © The British Library Board.

Buddhist text, Vessantara Jataka, showing Sogdian “Sutra Script.” Dated to ca. 8th–9th century CE. Ink on paper; L. 48.5 x W. 14.7 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France, département des Manuscrits. Pelliot chinois 3511 [Pelliot Sogdien1].

Photograph © Bibliotheque nationale de France, Paris.

Fragmentary decorated Manichean text in Manichean script, ca. mid-8th to early 11th century CE. Ink, pigments, and gold on silk; H. 7.4 x W. 6 cm. Berlin, Museum für Asiatische Kunst: MIK III 4981a.

After Zsuzsanna Gulácsi, Manichaean Art in Berlin Collections (Turnhout: Brepols, 2001), 167, fig. 75.1.

Christian text in Syriac script. Selection from Sayings of the Desert Fathers, entitled “Sayings of the Old Men.” Found in Bulayïq, near Turfan, Xinjiang, ca. 9th century CE. Ink on paper; H. 31.5 x W. 19 cm.

Deposit of Berlin–Brandenburg Academy of Sciences, Berlin State Library—Prussian Cultural Heritage, Orient Dept., n 489, recto.

Bilingual Sanskrit–Sogdian medical prescription for eye diseases. Presumably from somewhere in the Turfan region, ca. 9th century CE. Ink on paper; H. 10 x W. 14.7 cm.

Deposit of Berlin–Brandenburg Academy of Sciences, Berlin State Library—Prussian Cultural Heritage, Orient Dept., M(ain)z 0639, side 1.