Sogdian Fashion

by Betty Hensellek

Sogdian wall paintings showcase a world of fashion bursting with strong silhouettes and bold designs. Whether the wearers are men or women, nobles or servants, vividly patterned fabrics compose Sogdians’ garments.

Although we possess a remarkable collection of wall paintings illustrating Sogdian dress, few textiles with archaeological provenance survive from Sogdiana to provide clues as to what the people actually wore. Most contemporary textiles come from burials in neighboring regions in the northern Caucasus to the west, and from the Tarim and Turfan basins to the east. Because Sogdian religion forbade burial, preservation of textiles is all the rarer, and only a few textile assemblages survive. A large number of woven and knit cotton, silk, and wool fragments were excavated in 1933 from the citadel at Mount Mugh . The only intact garment so far found in an archaeological context is a cotton child’s kaftan, excavated in 2009 from the citadel at Sanjar-Shah in Tajikistan Fig. 1. Beyond a small corpus of excavated textiles, we should exercise caution when considering textiles that are without a secure provenance but are attributed to 7th- and 8th-century Sogdiana.

Fig. 1 Child’s cotton kaftan from Sanjar-Shah now at the Rudaki State Museum, Panjikent, Tajikistan, photographed in 2013. View object page

Photograph courtesy of Judith A. Lerner.

Representations in wall paintings of the clothing of deities, kings, and epic heroes are often fantastical, pastiches, or archaic. Although figures engaged in activities such as banqueting or worship are more realistic, they are still idealized. This essay focuses on three primary outerwear fashions that Sogdians really wore: the kaftan, robe, and tunic.

The Kaftan

The men’s kaftan is classic, highly versatile, and serves for multiple occasions, much like the modern-day suit. The kaftan’s design is built around four key elements: long sleeves, a tailored bodice, an attached skirting, and most essentially, front panels that close one over the other and have the ability to turn out and form lapels Fig. 2. These four elements consistently define the kaftan, but variations update this classic Sogdian fashion staple. For example, in the mid-7th century the skirting hangs close to the body, softening the body’s curves to create a slim H-line silhouette Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Detail, west wall of the “Hall of the Ambassadors”: The three men on the left wear long, polychrome tunics with side vents, while the two on the right wear slimming, H-line silhouette kaftans at a ceremony. Afrasiab (present-day Samarkand), Uzbekistan (in ancient Sogdiana), Site XXIII:1, mid-7th century CE. Wall painting; H. 3.4 m × W. 11.52 m. Afrasiab Museum. View object page

Photograph by Thorsten Greve © Association pour la sauvegarde de la peinture d’Afrasiab, and Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

By the early 8th century, an hourglass silhouette is in, with the skirting’s flare widened and the sleeves gathered Fig. 4. These design features accentuate broad shoulders and a wasp-thin waist, illuminating the idealized masculine body type of 8th-century Sogdian elites.

Fig. 4 Seated guests and a servant (far left) wearing kaftans with an hourglass silhouette at a formal banquet. Panjikent, Tajikistan (in ancient Sogdiana), Site XVI:10, first half of 8th century. Wall painting; H. 136 cm × W. 364 cm. The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, SA-16215-16217.

Photograph © The State Hermitage Museum.

Men wear the kaftan for a variety of social occasions. For example, at banquets all attendees wear kaftans, but at ceremonial events, some participants wear the kaftan and others an equally elaborate tunic. Regardless of the type of event, Sogdians pair the kaftan with knee-high boots that hide trouser legs, and jewelry, especially bracelets. A belt always secures the kaftan, and, depending on the occasion, a specific selection of accessories and weaponry hang from the belt.

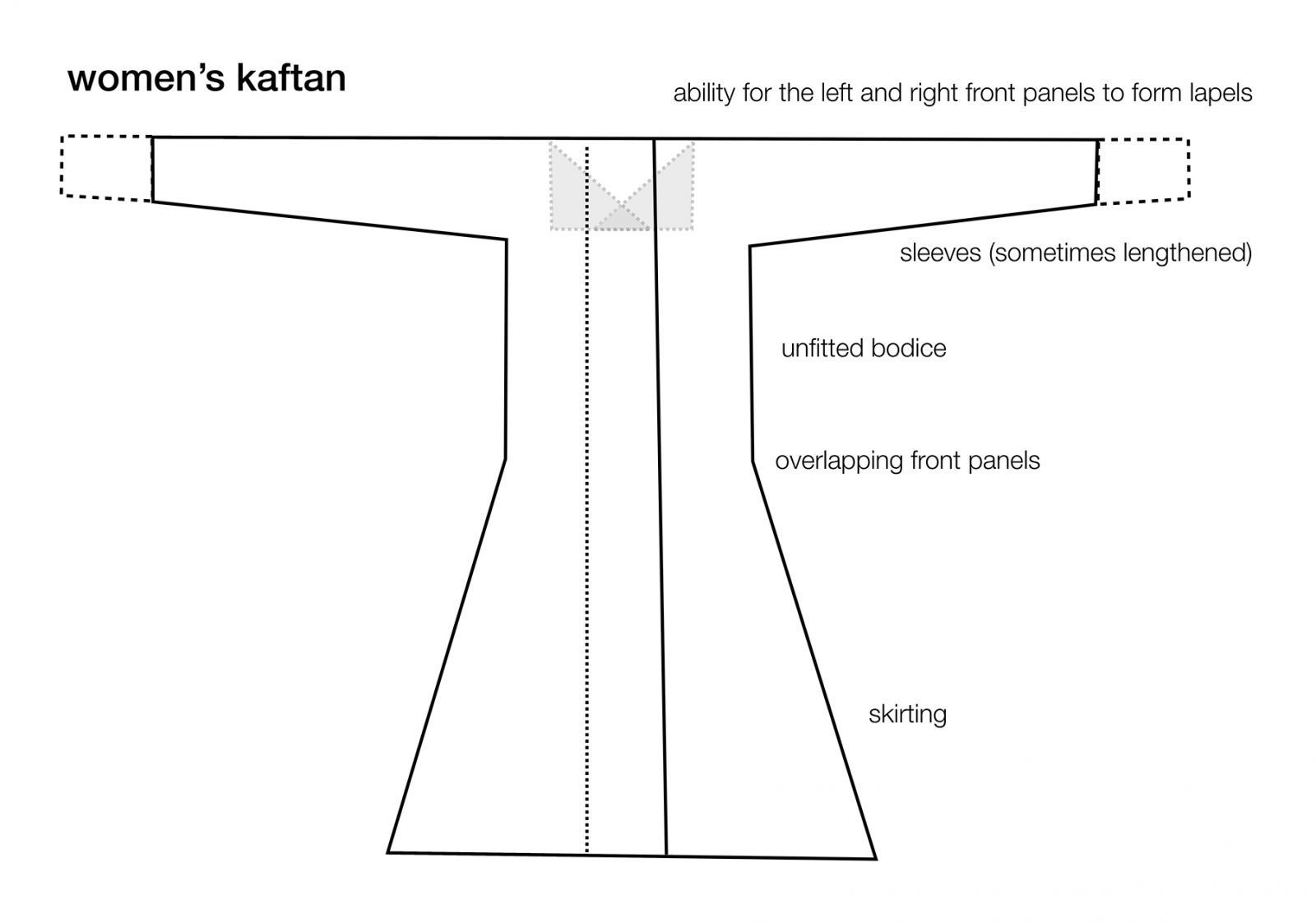

Although the same essential design elements comprise the woman’s kaftan, there is a difference in the bodice, which is not form-fitting in order to accommodate the curves of a woman’s body Fig. 5.

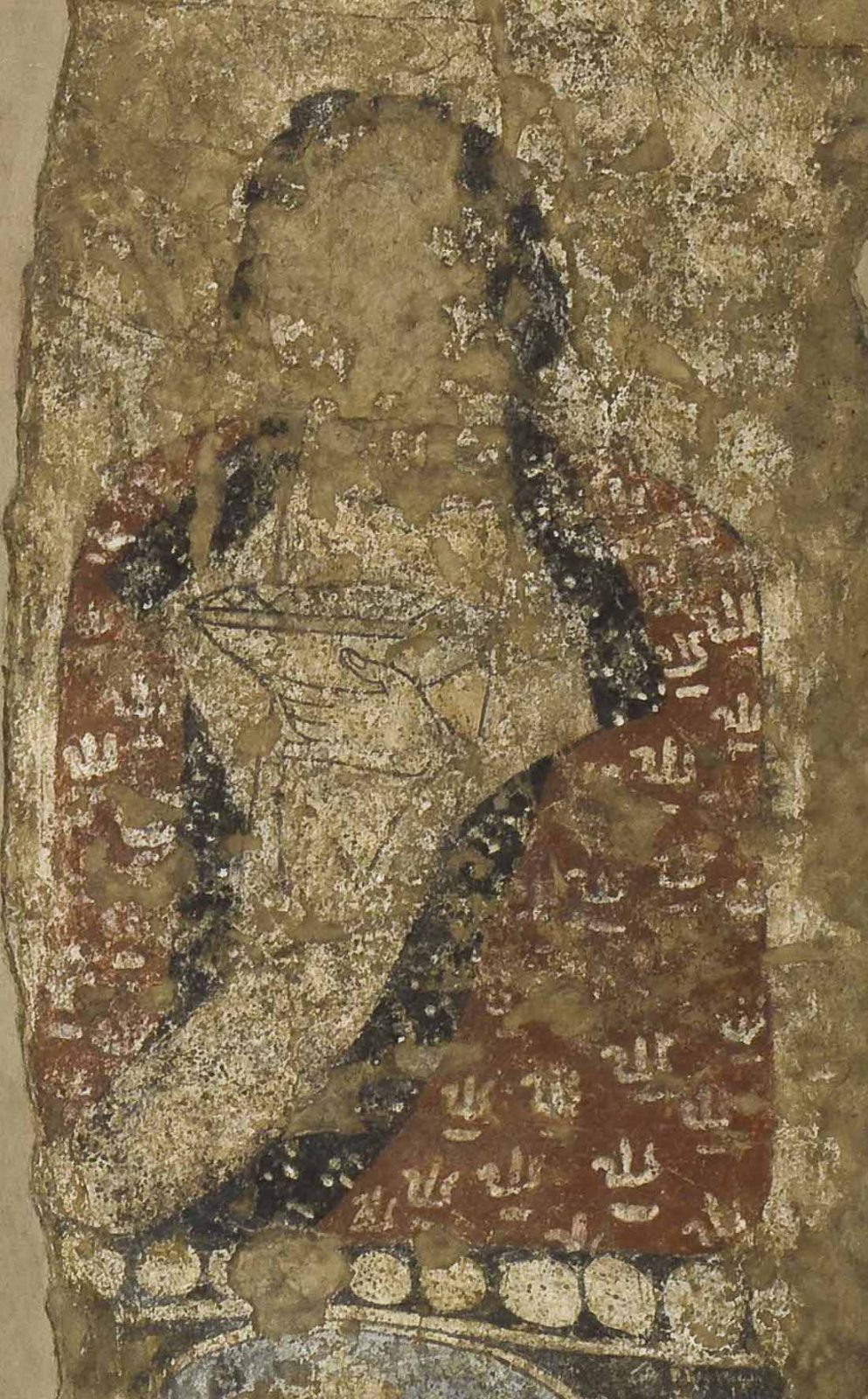

Fig. 6 Shiva with Trisula. Sogdian, 7th–8th century CE. Room in a Panjikent house, VII/24. Sogdian, 7th-8th century. Painted wood panel; H: 154 x L:147 cm. The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg, V-2704. View object page

Photograph © The State Hermitage Museum.

Fig. 7 Detail of Shiva with Trisula. A woman wearing a kaftan draped over her shoulders sits before the Indian god Shiva. Sogdian, 7th–8th century CE. Room in a Panjikent house, VII/24. Painted wood panel; H. 154 x W. 147 cm. The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, V-2704. View object page

Photograph © The State Hermitage Museum.

In images of worship, women wear the kaftan alongside men, but distinctively drape it over the shoulders with the sleeves left empty to hang at their sides Figs. 6 and 7. At Balalyk Tepe in southern Uzbekistan (neighboring medieval Tokharistan), a set of wall paintings suggests that a kaftan draped over the shoulders was also proper attire for women at formal banquets; their dress and seating positions furthermore indicate their elevated social status among the men.

The Robe

Exclusively intended for men, the robe is an outer garment usually worn on horseback and in battle Figs. 8–10.

Fig. 9 Detail from the Rustam Cycle: Rustam’s opponent, Lord Avlad, wears a robe over chain mail. Panjikent, Tajikistan (in ancient Sogdiana), Site VI:41, ca. 740 CE. Wall painting; The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, SA-15901-15904. View object page

Photograph © The State Hermitage Museum.

Fig. 10 Detail from the Rustam Cycle: Lord Avlad. Panjikent, Tajikistan (ancient Sogdiana), Site VI:41, ca. 740 CE. Wall painting. The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, SA-15901-15904. View object page

Photograph © The State Hermitage Museum.

Like the kaftan, the robe has sleeves, a fitted bodice, and long skirting. However, its front-panel closure is distinct. Unlike the kaftan, the front panels are triangular and not rectangular, so that when crossed, they create a V-shaped (or surplice) neckline that does not form lapels, much in the manner of a modern wrap dress or bathrobe.

The robe has fewer design updates than the kaftan, preserving the V-line silhouette from the 6th century through the 8th. The shoulders remain broad and the belted waist thin, with a straight skirting that carries the slenderness through the legs. Only the sleeve length of the robe varies. For example, in battle, the sleeve is shorter when worn over chain mail. The robe is usually paired with tall boots, and two deep cuts or vents into either side of the narrow skirting allow for ease of movement. Jewelry rarely accompanies the robe, given its occasions of use.

The Tunic

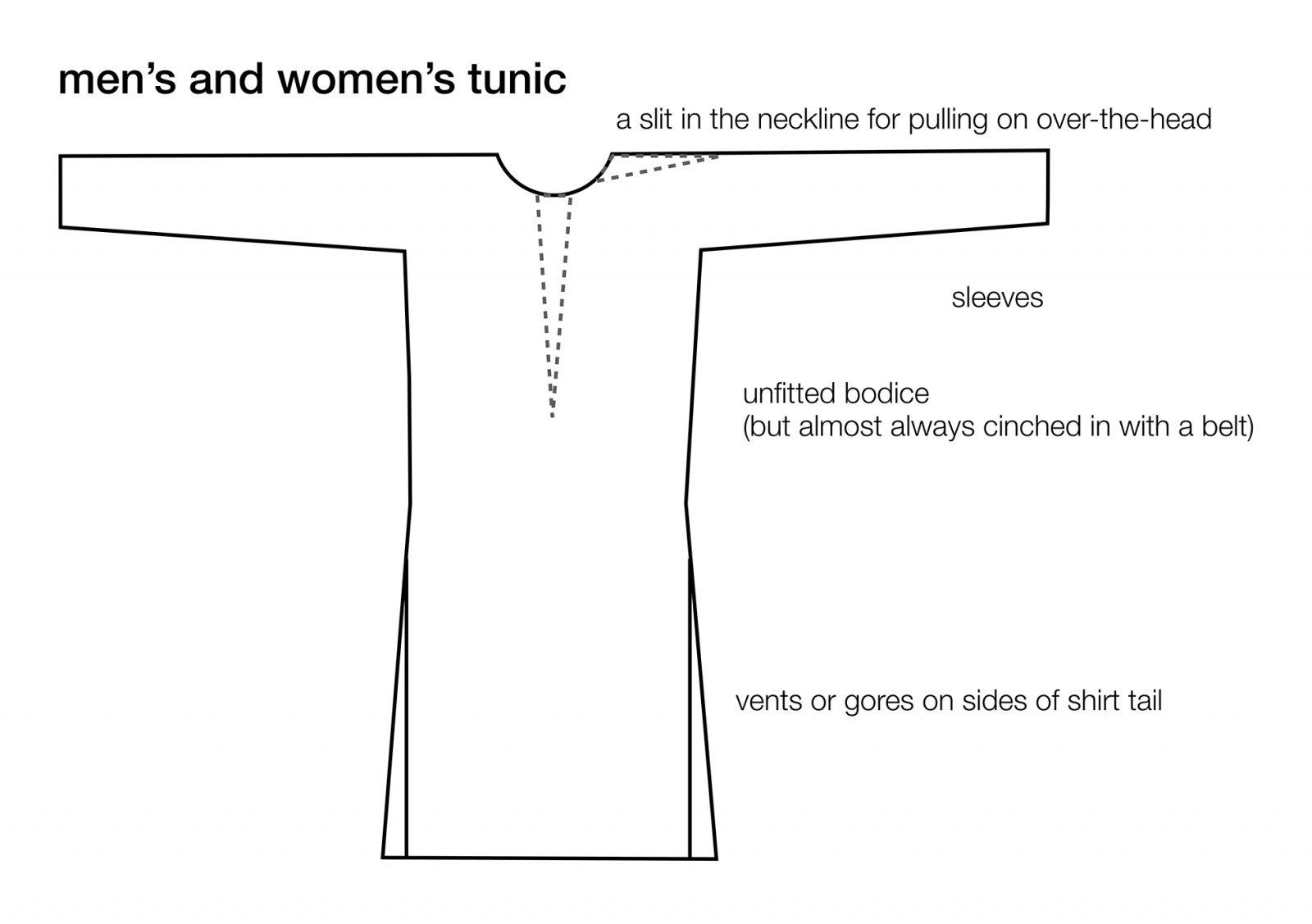

The most prevalent garment type is the tunic, worn by both men and women and across all social strata Fig. 11.

The Sogdian tunic has a number of variations, among which are a lower hem length, a separate pattern piece for the shoulders (yoke), or sleeve gathers. All of these are consistent with gender and the activity for which the tunic is worn. However, the variety of added trims and embellishments creates a superficially broad array of styles. The tunic’s basic pattern is boxy, but made form-fitting on the upper body by cinching excess fabric with a belt. In men’s tunics, fabric tails hang loosely below the waist, with vents cut into either side. In women’s tunics, triangular-shaped fabric inserts (gores) add volume. The tunic differs fundamentally from a kaftan or robe in that it does not fasten in the front. Instead it is pulled on over the head like a T-shirt, aided by a vertical slit in the neckline; Figs. 12 and 13.

Fig. 12 In the Rustam Cycle, the hero Rustam wears a leopard-spotted tunic as he takes on his challengers. Panjikent, Tajikistan (in ancient Sogdiana), Site VI:41, ca. 740 CE. Wall painting; The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, SA-15901-15904. View object page

Photograph © The State Hermitage Museum.

Fig. 13 Detail of the hero Rustam. Panjikent, Tajikistan (in ancient Sogdiana), Site VI:41, ca. 740 CE. Wall painting; The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, SA-15901-15904. View object page

Photograph © The State Hermitage Museum.

Patterns and Fabrics

The Sogdians seem to have carefully selected the fabric colors and patterns of their garments. They combined two contrasting fabrics—often a small, tight pattern with a larger, monochromatic one, respectively—for the decorative trim and body. Trims adorned cuffs, necklines, frontal openings, vents, and lower hems. Tunics also included ornamental strips of fabric placed on the bodice, skirting, shoulder, or sleeves.

Many of the fabrics depicted in the paintings may be woven silks, but based on surviving textiles, the most prevalent fabric was cotton. Woven fabric patterns that survive range from so-called “pearl roundels” and rosettes to stripes and plaids. In addition to patterns woven into the fabric, the Sogdians used a resist-dyeing technique to create patterns similar to those of Japanese shibori.

For extant Sogdian textiles from the northern Caucasus, see, for example, Z. V. Dode, Srednevekovyy kostyum narodov severnogo kavkaza Средневековый костюм народов Северного Кавказа [Medieval costume of the peoples of the North Caucasus] (Moscow: Eastern Literature Publishing House, 2001); as well as Anna Ierusalimskaya and Birgitt Borkopp, Von China nach Byzanz: Frühmittelalterliche Seiden aus der Staatlichen Ermitage Sankt Petersburg (Munich and St. Petersburg: Bayerischen Nationalmuseums and Staatlichen Ermitage, 1996), and Anna Ierusalimskaya, Moshchevaja Balka: Neobychnyy arkheologicheskiy pamyatnik na Severo-Kavkazskom shelkovom puti Мощевая Балка: Необычный археологический памятник на Северо-Кавказском шелковом пути [Moshchevaya Balka: An Unusual Archaeological Site on the North Caucasian Silk Road]. (St. Petersburg: State Hermitage Publishing House, 2012). For surviving textiles of the Tarim and Turfan basins, see Alfried Wieczorek and Christoph Lind, eds., Ursprünge der Seidenstraße: Sensationelle Neufunde aus Xinjiang, China (Stuttgart: Theiss Verlag; Mannheim: Reiss-Engelhorn-Museen, 2007); and Zhao Feng 赵丰 and Qi Dongfang 齐东方, eds. Jin shang hu feng: Sichou zhi lu fangzhi pin shang de xifang yingxiang, 4–8 shiji 錦上胡風: 丝绸之路纺织品上的西方影响: 4–8 世纪 [New Designs with Western Influence on the Textiles of Silk Road from the 4th Century to 8th Century] (Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe, 2011).

Around 150 fragments were found and are now divided between the State Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg, Russia, and the Museum of National Antiquities in Dushanbe, Tajikistan. See the list of finds in I. B. Bentovich, “Nakhodki na gore Mug: Sobraniye gosudarstvennogo Ermitazha” Находки на горе Муг: Собрание государственного Эрмитажа [Finds at Mount Mugh: Materials in the State Hermitage]. Materialy i issledоvaniia po Arkheologii SSSR 66 (1958): 358–83.

Kurbanov, Sh., and A. Teplyakova. “Textile Objects from the Citadel of Sanjar-Shah.” Bulletin of Miho Museum 15 (2014): 167–77.

Other small fragments of textiles have been excavated in Sogdiana proper. There are intact garments from the neighboring regions of Ferghana to the east (northeastern Uzbekistan and southwestern Kyrgyzstan) and Tokharistan to the south (southern Uzbekistan and northern Afghanistan). These include late 6th- to early 7th-century Munchak Tepe and 4th- to 5th-century Kurgan, located just north of Old Termez. For Munchak Tepe, see Bokijon Kh. Matbabaev and Zhao Feng, Da wan yi jin: Wuzibiekesitan Fei’erganna Mengqiatepei chutu de fangzhi pin yanjiu 大宛遗锦:乌兹别克斯坦费尔干纳蒙恰特佩出土的纺织品研究 / Ткани и одежда раннесредневековой ферганы [Early Medieval Textiles and Garments of the Ferghana Valley: By Materials from the Burial Ground of Munchaktepa in Uzbekistan] (Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe, 2010). For Kurgan, see A. K. Elkina, G. M. Maitdinova, and V. A. Kozlovsky, “Odezhda kontsa IV–V vv. iz Starogo Termeza” Одежда конца 4–5 вв. из Старого Термеза [Dress at the end of the 4th–5th centuries from Old Termez], in Buddiyskiy Kompleks Kara-Tepe v Starom Termeze: Osnovnyye itogi rabot 1978–1989 gg Буддийский Комплекс Кара-Тепе в Старом Термезе: Основные итоги работ 1978–1989 гг [The Buddhist Complex of Kara-Tepe in Old Termez: Main Field Reports 1978–1989], ed. B. Ia. Stavisky (Moscow: Eastern Literature Publishing House, 1996), 307–26; and G. M. Majtdinova, Kostium rannesrednevekogo Tokharistana: Istoriia i svyazi [Costume of Early Medieval Tokharistan: History and Connections] (Dushanbe: Donish, 1992).

In recent years, so-called Sogdian textiles and garments—all without provenance—have flooded the art market. The fabrication of a Sogdian silk production site at Zandana has helped to fuel demands. The historiography of this mythical site and its production is known to specialists as the “Zandaniji problem.” See Nicholas Sims-Williams and Geoffrey Khan, “Zandaniji Misidentified,” Bulletin of the Asia Institute 22 (2008 [2012]): 207–13; and Zvezdana Dode, “‘Zandanījī Silks’: The Story of a Myth,” The Silk Road 14 (2016): 213–22. http://www.silkroadfoundation.org/newsletter/vol14/Dode_SR14_2016_213_222.pdf

This silhouette is mirrored—probably to exaggeration—in the plated armor of warriors in battle narratives. See, for example, Boris I. Marshak [Marschak/Maršak], “La thématique sogdienne dans l’art de la Chine de la seconde moitié du Vie siècle,” Comptes rendus des séances de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres 145, no. 1 (2001): figs. 52, 55, 100.

The lower portion of a soft leather boot was found at Mount Mugh; see I. B. Bentovich, “Nakhodki na gore Mug: Sobraniye gosudarstvennogo Ermitazha” “Находки на горе Муг: Собрание государственного Эрмитажа” [Finds at Mount Mugh: Materials in the State Hermitage],” Materialy i issledоvaniia po Arkheologii SSSR 66 (1958): 371, fig. 6-1. Three pairs of earlier 4th- to 5th-century trousers were excavated from Kurgan, north of Old Termez, in southern Uzbekistan; see A. K. Elkina, G. M. Maitdinova, and V. A. Kozlovsky, “Odezhda kontsa IV–V vv. iz Starogo Termeza” “Одежда конца 4–5 вв. из Старого Термеза” [Dress at the end of the 4th–5th centuries from Old Termez]. In Buddiyskiy Kompleks Kara-Tepe v Starom Termeze: Osnovnyye itogi rabot 1978–1989 gg. Буддийский Комплекс Кара-Тепе в Старом Термезе: Основные итоги работ 1978–1989 гг [The Buddhist Complex of Kara-Tepe in Old Termez: Main Field Reports 1978–1989], ed. B. Ia. Stavisky, 307–26 (Moscow: Eastern Literature Publishing House, 1996), 312–14, figs. 92, 93. A greater number of trousers survive from burials in western China; see Alfried Wieczorek, and Christoph Lind, eds., Ursprünge der Seidenstraße: Sensationelle Neufunde aus Xinjiang, China (Stuttgart: Theiss Verlag; Mannheim: Reiss-Engelhorn-Museen, 2007). A variety of silver, gold, and bronze jewelry—rings, pendants, and earrings—have been excavated from Panjikent; see A[lexander] M. Belenitsky [Belenizki], I. B. Bentovich, and O. G. Bolshakov, Srednevekovyy gorod sredneii Azii Средневековый город среднеии Азии [The Medieval City of Central Asia] (Leningrad: Nauka Publishing House 1973), l, 83–86, figs. 51–52.

For a study of Sogdian belts, see V. I. Raspopova, “Poyasnoi nabor Sogda VII–VIII vv” Поясной набор Согда VII-VIII вв [Belt Sets of Sogdiana, VII–VIII century], Sovetskaya Arkheologiya Советская Археология 4 (1965): 78–91; A[lexander] M. Belenitsky [Belenizki] and V. I. Raspopova, “Sogdiiskiye ‘zolotyye Poyasa’” Согдийские ‘золотые Пояса’ [Sogdian “Golden Belts”], in Strany i narody Vostoka Страны и народы Востока [Countries and Peoples of the East] 22 (1980): 213–18.

This mode of wearing an outer garment, draped over the shoulders, is also found on small terracotta figurines of women; see Fiona J. Kidd, “Costume of the Samarkand Region of Sogdiana between the 2nd/1st Century B.C.E. and the 4th Century C.E.,” Bulletin of the Asia Institute 17 (2003): 35–69.

The author is investigating the ways in which both men and women wore the kaftan for a formal banquet in Tokharistan according to the wall paintings from Balalyk Tepe in a future publication with the German Archaeological Institute.

For instance, women wear tunics with tulip-shaped yokes for horseback riding; see Boris I. Marshak [Marschak/Maršak], Legends, Tales, and Fables in the Art of Sogdiana (New York: Bibliotheca Persica Press, 2002), fig. 73. Men wear a long, ankle-length tunic with gathered sleeves and a single strip of fabric down the chest in 6th- and 7th-century scenes of worship; see Belenitsky [Belenizki], A[lexander] M. Kunst der Sogden (Leipzig: E. A. Seemann, 1980), 42; Boris I. Marshak [Marschak/Maršak], “La thématique sogdienne dans l’art de la Chine de la seconde moitié du VIe siècle,” Comptes rendus des séances de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres 145, no. 1 (2001): 227–64.

Gores are not clear in wall paintings, but are known from surviving textiles in southern Uzbekistan. To illustrate, see the women’s tunic in the collection of the Termez Archaeological Museum from Kurgan in Uzbekistan, north of Old Termez. See G. M. Maitdinova [Majtdinova], Kostium rannesrednevekovogo Tokharistana: istoriia i svyazi Костюм раннесредневекового Тохаристана: история и связи [Costume of Early Medieval Tokharistan: History and Connections] (Dushanbe: Donish, 1992), pls. 25 and 26.

A number of tunics with variously slitted necklines survive from Munchak Tepe in neighboring Ferghana. See Bokijon Kh. Matbabaev and Zhao Feng, Da wan yi jin: Wuzibiekesitan Fei’erganna Mengqia Tepei chutu de fangzhi pin yanjiu. 大宛遗锦:乌兹别克斯坦费尔干纳蒙恰特佩出土的纺织品研究/Ткани и одежда раннесредневековой ферганы [Early Medieval Textiles and Garments of the Ferghana Valley: By Materials from the Burial Ground of Munchaktepa in Uzbekistan] (Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe, 2010), pls. A-6, B-3, C-6, D-6, D-9, E-2, X-1, X-2. Most of these slits in archaeological textiles are decorative, but they could also have been more discreet, as shown in a 6th-century wall painting with donors from Temple II, Panjikent. Here, the tunic has a tie along one shoulder; A[lexander] M. Belenitsky [Belenizki], Kunst der Sogden (Leipzig: E. A. Seemann, 1980), fig. 18.

See the list of textiles found at Mount Mugh; I. B. Bentovich, “Nakhodki na gore Mug: Sobraniye gosudarstvennogo Ermitazha”

Находки на горе Муг: Собрание государственного Эрмитажа [Finds at Mount Mugh: Materials in the State Hermitage]. Materialy i issledоvaniia po Arkheologii SSSR 66 (1958): 373–83.

To create shibori the fabric can be wrapped, bound, folded, or stitched, depending on the pattern desired. Thus, when the fabric is dipped into the dye, the exposed cloth will take the dye color, while those areas covered by thread, clamps, and so on will remain their original color. Tie-dyeing in the United States with string or rubber bands is a form of this technique, called kanoko shibori. One example from Mount Mugh is on display in the Museum of National Antiquities, Dushanbe; another is a fragment from Kurgan, north of Old Termez, now in the State Museum of History of Uzbekistan, Tashkent; see G. M. Majtdinova, Kostium rannesrednevekovogo Tokharistana: Istoriia i svyazi Костюм раннесредневекового Тохаристана: история и связи [Costume of Early Medieval Tokharistan: History and Connections] (Dushanbe: Donish, 1992), 77, pl. 4.

Child’s cotton kaftan from Sanjar-Shah now at the Rudaki State Museum, Panjikent, Tajikistan, photographed in 2013.

Photograph courtesy of Judith A. Lerner.

Basic pattern for a men’s kaftan.

Drawing by Betty Hensellek.

Detail, west wall of the “Hall of the Ambassadors”: The three men on the left wear long, polychrome tunics with side vents, while the two on the right wear slimming, H-line silhouette kaftans at a ceremony. Afrasiab (present-day Samarkand), Uzbekistan (in ancient Sogdiana), Site XXIII:1, mid-7th century CE. Wall painting; H. 3.4 m × W. 11.52 m. Afrasiab Museum.

Photograph by Thorsten Greve © Association pour la sauvegarde de la peinture d’Afrasiab, and Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

Seated guests and a servant (far left) wearing kaftans with an hourglass silhouette at a formal banquet. Panjikent, Tajikistan (in ancient Sogdiana), Site XVI:10, first half of 8th century. Wall painting; H. 136 cm × W. 364 cm. The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, SA-16215-16217.

Photograph © The State Hermitage Museum.

Basic pattern for a women’s kaftan.

Drawing by Betty Hensellek.

Shiva with Trisula. Sogdian, 7th–8th century CE. Room in a Panjikent house, VII/24. Sogdian, 7th-8th century. Painted wood panel; H: 154 x L:147 cm. The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg, V-2704.

Photograph © The State Hermitage Museum.

Detail of Shiva with Trisula. A woman wearing a kaftan draped over her shoulders sits before the Indian god Shiva. Sogdian, 7th–8th century CE. Room in a Panjikent house, VII/24. Painted wood panel; H. 154 x W. 147 cm. The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, V-2704.

Photograph © The State Hermitage Museum.

Basic pattern for a men’s robe.

Drawing by Betty Hensellek.

Detail from the Rustam Cycle: Rustam’s opponent, Lord Avlad, wears a robe over chain mail. Panjikent, Tajikistan (in ancient Sogdiana), Site VI:41, ca. 740 CE. Wall painting; The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, SA-15901-15904.

Photograph © The State Hermitage Museum.

Detail from the Rustam Cycle: Lord Avlad. Panjikent, Tajikistan (ancient Sogdiana), Site VI:41, ca. 740 CE. Wall painting. The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, SA-15901-15904.

Photograph © The State Hermitage Museum.

Basic pattern for a men’s and women’s tunic.

Drawing by Betty Hensellek.

In the Rustam Cycle, the hero Rustam wears a leopard-spotted tunic as he takes on his challengers. Panjikent, Tajikistan (in ancient Sogdiana), Site VI:41, ca. 740 CE. Wall painting; The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, SA-15901-15904.

Photograph © The State Hermitage Museum.

Detail of the hero Rustam. Panjikent, Tajikistan (in ancient Sogdiana), Site VI:41, ca. 740 CE. Wall painting; The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, SA-15901-15904.

Photograph © The State Hermitage Museum.