The Rustam Cycle

Panjikent, Tajikistan (in ancient Sogdiana), Sector VI, Room 41, ca. 740 CE

Wall painting (distemper paints on dry loess plaster)

The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, SA-15901-15904

Photograph © The State Hermitage Museum.

Contrary to what one might expect, the impressive set of wall paintings known as the “Rustam Cycle” was not located in the hall of a royal palace, but in a house of average size in Panjikent,The City of Panjikent and Sogdian Town-Planning Learn more about Panjikent and Sogdian town-planning a small town sixty kilometers east of Samarkand . This painting cycle stands out among other excavated examples for its exceptionally well-preserved (and now, well-restored) murals, which can be dated to about 740. It is also, ironically, the last of the magnificent cycles to be painted at Panjikent; Fig. 1. The city’s ruler, Devastich, was killed in 722 and the city itself subjected to punitive Arab incursions. Despite this artwork and other evidence of Panjikenters resuming their way of life, the city was finally abandoned after the 770s.

Fig. 1 Pavel Lurje (The State Hermitage Museum) discusses the wall paintings found at Panjikent, on display at the State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg.

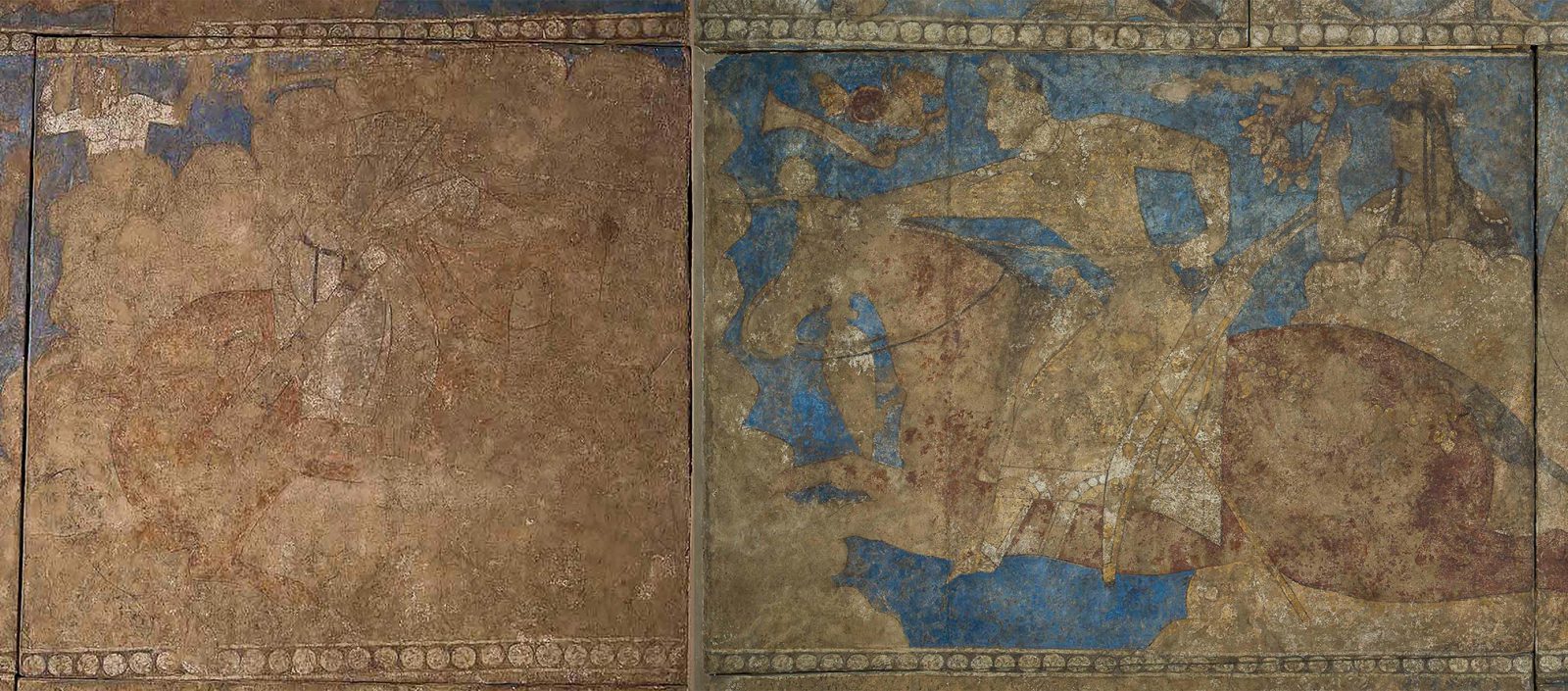

Discovered in 1956–57 by archaeologist Boris J. Stavisky, the Rustam Cycle is the most famous painted hall of Panjikent. Named after its main figure, Rustam, a major hero in the great Iranian epic the Shahnameh [“Book of Kings”], it is typical of narrative cycles found at Panjikent as well as other Sogdian cities, such as Afrasiab and Varakhsha . Episodes are organized into different registers, each running horizontally along the length of the walls. Here, the two main registers contain the stories of Rustam’s exploits and are set between a lower tier, depicting scenes from fables and moral tales, and an upper tier, illustrating a religious subject, perhaps related to a family cult; Fig. 2-8.

Fig. 3 Detail: Episode 1. Rustam, on his horse Rakhsh and accompanied by his men, sets out on a campaign against the demons. They ride into a wild and dangerous region, as suggested by the white figure perched atop a rocky outcropping, its arms raised in anger and despair at the sight of Rustam. This is the White Demon (Div-e Safid), one of Rustam’s adversaries in the Shahnameh.

Fig. 4 Detail: Episode 2. Rustam enters into his first battle against another horseman, whom Marshak identifies as Avlad, ruler of the borderlands through which Rustam is traveling. The hero is pictured throwing a lasso around his opponent’s neck, while behind him a benevolent female deity bestows her heavenly protection.

Fig. 5 Detail: Episode 3. Rustam is in great peril as he fights a dragon that has coiled itself around Rakhsh’s legs, pulling Rustam toward its gaping mouth. The painting does not show Rustam’s escape from this dire situation, but part of the Sogdian text offers a version of how he did: “Rustam turned back, attacked the demons like a fierce lion upon its prey or a hyena upon the flock, like a falcon upon a hare or a porcupine upon a snake, and began to destroy them.”

Fig. 6 Detail: Episode 4. Both Rustam and Rakhsh emerge unscathed. Together with Rustam’s men they trample the dragon, its tail rising in the air in a final, violent convulsion.

Fig. 7 Detail: Episode 5. Rustam and the ruler of the deevs meet in single combat. In the course of their fight, their saddle girths break and the two adversaries fall from their galloping horses. Their duel on foot should follow, but the artist has omitted Rustam’s success over his adversary.

Fig. 8 Detail: Episode 6. Rustam’s men in battle with the deevs. Their success is assured by the beribboned lion-bird that flies towards them. In contrast, their subhuman adversaries are followed by a vulture that signals their impending defeat.

Figs. 2-8 Click on the hotspots to view details of the Blue Hall mural and read about the various episodes in the story of Rustam. The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, SA-15901-15904.

Photograph © The State Hermitage Museum.

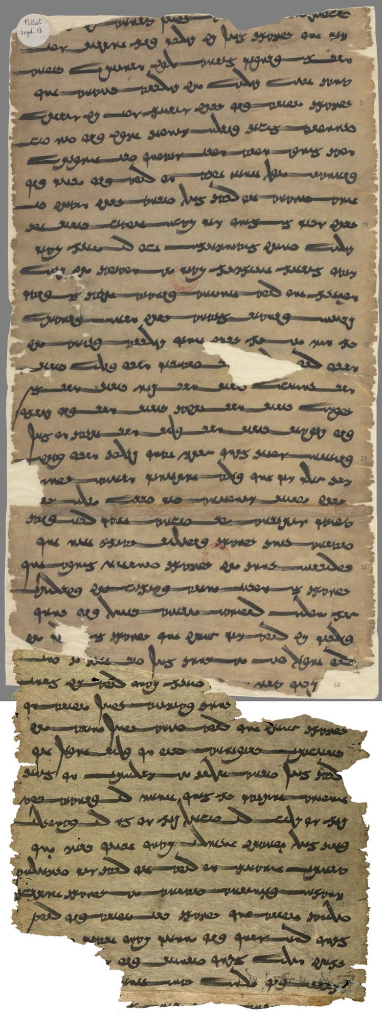

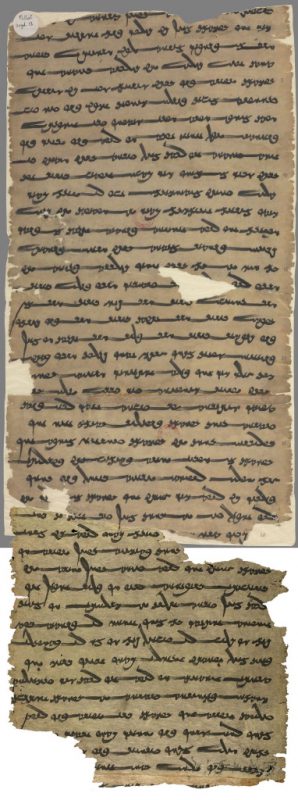

Fig. 9 Reconstruction of two fragments of Sogdian story Rustam and the Demons, 9th century CE, from Dunhuang, China. Pelliot Sogdien 13 (top), and Stein Ch. 00349 (bottom). British Library Or.8212/81.

Image after Nicholas Sims-Williams, “Sogdian Fragments in the British Library,” Indo-Iranian Journal 18, no. 1/2 (June/July 1976): 43–82.

The artist(s) of the Rustam Cycle chose to omit extraneous details like landscape elements, instead focusing entirely on the drama between figures and the action animating each scene. The color contrasts are bolder in the upper tiers devoted to the epics than in the lower register. The figures are depicted vividly in warm yellows, browns, and reds against a cool ultramarine background to attract the viewer’s attention and connect critical moments of the story. Two fragments of the Rustam story written in Sogdian have survived: one kept in the Bibliothèque nationale de France, the other in the British Library; Fig. 9. Dated to the 9th century, they predate by 200 years the first complete version of the Shahnameh written in Persian by the poet Firdowsi.

by Julie Bellemare and Judith A. Lerner

Guitty Azarpay, Sogdian Painting: The Pictorial Epic in Oriental Art (Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press, 1981), 95.

Nicholas Sims-Williams, “Sogdian Fragments in the British Library,” Indo-Iranian Journal 18, nos. 1–2 (June/July 1976): 43–82.

Boris I. Marshak and Vladimir A. Livshits, Legends, Tales, and Fables in the Art of Sogdiana (New York: Bibliotheca Persica Press, 2002), 39.

Adapted from Nicholas Sims-Williams, “Sogdian Fragments in the British Library,” Indo-Iranian Journal 18, nos. 1–2 (June/July 1976): 57–58.