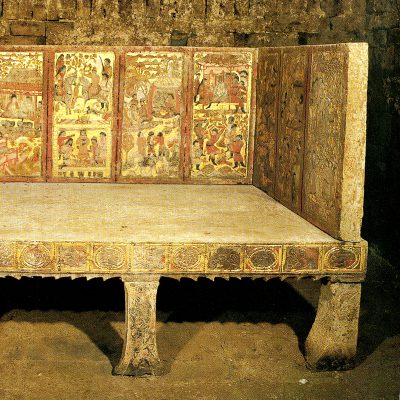

Mourning Scene

Panjikent, Tajikistan , south wall of main hall of Temple II

Wall painting, 6th century CE

Excavated in 1948

The State Hermitage Museum, SA-16236

Photograph © The State Hermitage Museum

This fragmentary wall painting from the main hall of Temple II in Panjikent is one of the best-known discoveries from the early years of systematic excavation of the city in the late 1940s. A vivid and complex composition depicts the lamentation for the deceased, who is visible through the three arches of a domed structure. The body is dressed in red with long tresses and an elaborate headdress. Through the arches we can also see three mourning women tearing their hair; below, men and women also mourn, with the men cutting their beards. To the left of the composition appear three larger figures. The largest is a standing, haloed, four-armed goddess; to her right, another haloed figure, yet to be identified, kneels and seems to sweep the ground in front of the standing deity. Behind them stands a third figure, her left arm raised and her right holding an unidentified object.

The painting contains several layers of recessed space, an unusual composition when compared to later examples excavated from elsewhere in Panjikent, which approach pictorial space in a flatter and more abstract manner. Nonetheless, a constant in Panjikent’s wall paintings is a focus on drama and narrative, something that is poignantly expressed in this scene.

Initially thought to depict an episode from the great Iranian epic the Shahnameh [“Book of Kings”], scholars later connected the painting to texts describing mourning rituals strikingly similar to actions in the scene here. The large, four-armed deity has been identified as Nana, a major goddess whose origins can be traced back to Mesopotamia in the third millennium BCE. Nana was worshipped by rulers, from Sumerian kings to Kushan emperors, and was adopted in Sogdiana, where her cult spread to all strata of the population. Both wood carvings and monumental paintings of her (typically on her lion mount) decorated many Panjikenters’ houses; Fig. 1.

Temple II at PanjikentThe City of Panjikent and Sogdian Town-Planning Learn more about Panjikent and Sogdian town-planning appears to have been dedicated to her, with several remaining wall paintings of female deities, and at least two sculptures of women sitting on lions discovered in the outer gate area of the temple. Her four arms derive from Indian representations of divinities. So, too, may the reclining posture of the deceased, which is akin to parinirvana, or portrayals of the Buddha’s passing. However, Frantz Grenet and Boris I. Marshak Boris Marshak Learn more about the Russian scholar Boris Marshak suggested that the event pictured is an agrarian ritual in which the symbolic death of a deity allows for the return of good harvests. This serves as a reminder of the fundamentally agrarian nature of life in Sogdiana.

Boris Marshak Learn more about the Russian scholar Boris Marshak suggested that the event pictured is an agrarian ritual in which the symbolic death of a deity allows for the return of good harvests. This serves as a reminder of the fundamentally agrarian nature of life in Sogdiana.

by Julie Bellemare and Judith A. Lerner

Frantz Grenet and Boris Ilich Marshak, “Le mythe de Nana dans l’art de la Sogdiane,” Arts Asiatiques 53 (1998): 6.

See Joan Goodnick Westenholz, “Trading the Symbols of the Goddess Nanaya,” in Religions and Trade: Religious Formation, Transformation and Cross-Cultural Exchange between East and West (Leiden: Brill, 2014), 167–98.

Grenet and Marshak posited that the deceased could be identified as Geshtinanna, the sister of the ancient Mesopotamian god Dumuzid (Tammuz). Her cyclical death was thought to produce the seasons, thus enabling the first appearance of wheat. Frantz Grenet and Boris I. Marshak [Marschak/Maršak], “Le mythe de Nana dans l’art de la Sogdiane,” Arts Asiatiques 53 (1998): 9.